Today is Spirit Day, an annual event in which millions wear the color purple to take a stand against the bullying of LGBT youth. And despite much progress in recent years, this problem still plagues our nation's schools. Young lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender kids are at an increased risk of bullying. Many experience verbal, physical, and emotional abuse from their peers, which leads to higher rates of depression and suicide.

To raise awareness of this issue, The Advocate asked adult LGBT folks to share their own experiences with bullying and how they responded to it. Read their stories below.

Astronomy class, senior year. For whatever reason, the topic of AIDS comes up. God knows why. Another student in the class turns around in his seat toward me and exclaims , "That's something you would know a lot about, huh, Andrew?" I'm stunned but prepared to just let it go, when before I know it, yet another student raises his voice: "Why don't you just shut the fuck up? No one thinks you're funny. Now leave him alone." This other student happened to be the football quarterback, a guy who I'd always thought was super hot, intimidating, and likely perturbed by the fact that I was gay. I will never, ever forget his words of protection that seemed to come out of nowhere. It made an enormous impact on me, and strengthened my belief in the notion that my identity was one worth cultivating, celebrating, and defending.

Today I work for Sharpe, a company that provides a safe place for LGBTQ people to find the right fit of clothing. In its own way, it raises its voice in defense of those who are bullied, providing those of us within the LGBTQ community (and beyond) a safe, supportive outlet to look and feel exactly how we deserve. I'm proud and humbled to be a part of such an incredible team, and do for others what was once done for me.

ANDREW DIEGO is the head of design and sales at the Sharpe Group. Learn more at www.sharpesuiting.com.

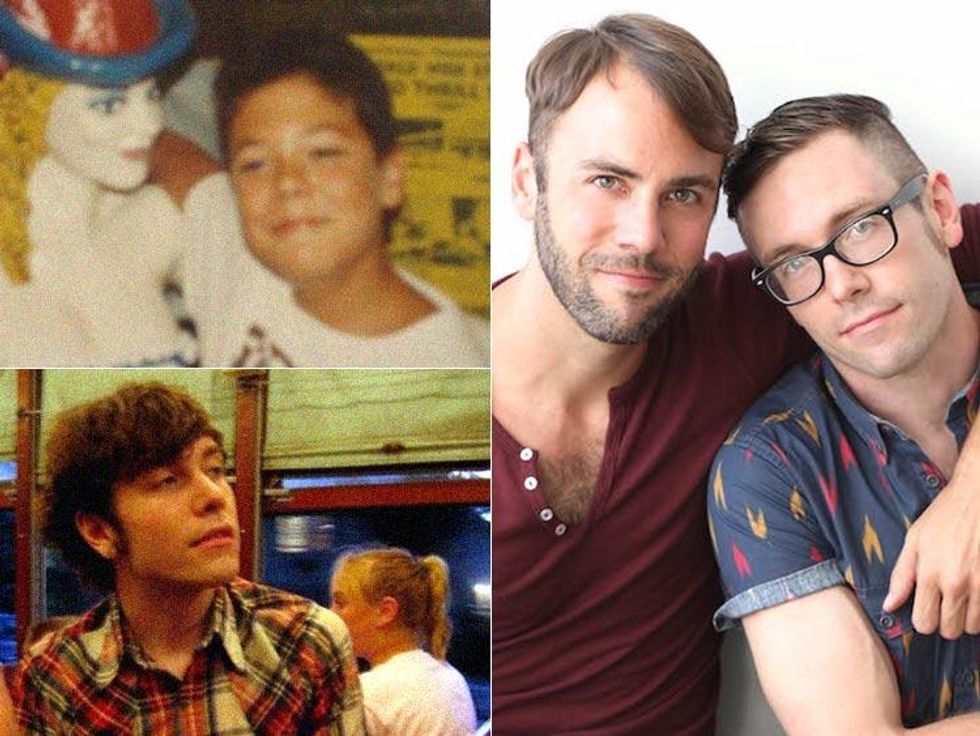

My fiance, John Halbach, and I had remarkably similar bullying experiences in our respective high schools in Minnesota and Mississippi. Neither of us was out, but groups of guys somehow sensed our otherness (perhaps because of John's love for Paula Abdul and my attempts to start a student-run theater). They called John "Gay Boy" and me "Gay Kid."

The low point of my high school experience was definitely art class, because the teacher was young and kind of enjoyed flirting with the upper-class jock table that tortured me. They'd also throw rocks at me and my friends between classes, and the school never did anything about it. But in art class, there was no escaping them. I had daily fantasies of pouring glue on their heads, which I'm glad I never did, because it probably would've kept me from getting into arts boarding school the next year. Things calmed down after I was elected to the honor council, a student jury that voted on issues of cheating, which meant I saw a lot of them.

The ringleader at John's school mostly tortured him at lunch -- he would eat on the floor in the corner to avoid them. Finally, John's mom called the school counselor, who told the bully if he didn't stop, he'd be charged with sexual harassment. I wish I'd gone to my parents about the guys in art class. I wish all my friends had gotten together and spoken to our parents together about the rocks. Looking back, I don't know why we all thought we were in it alone.

In high school, all I wanted was to find someone who understood what I was going through. And it turns out that overcoming bullying is one of a million amazing things my partner and I had in common.

KIT WILLIAMSON and his fiance, JOHN HALBACH, are actors and activists living in New York City. Their LGBT series, EastSiders, recently premiered its second season exclusively on Vimeo On Demand.

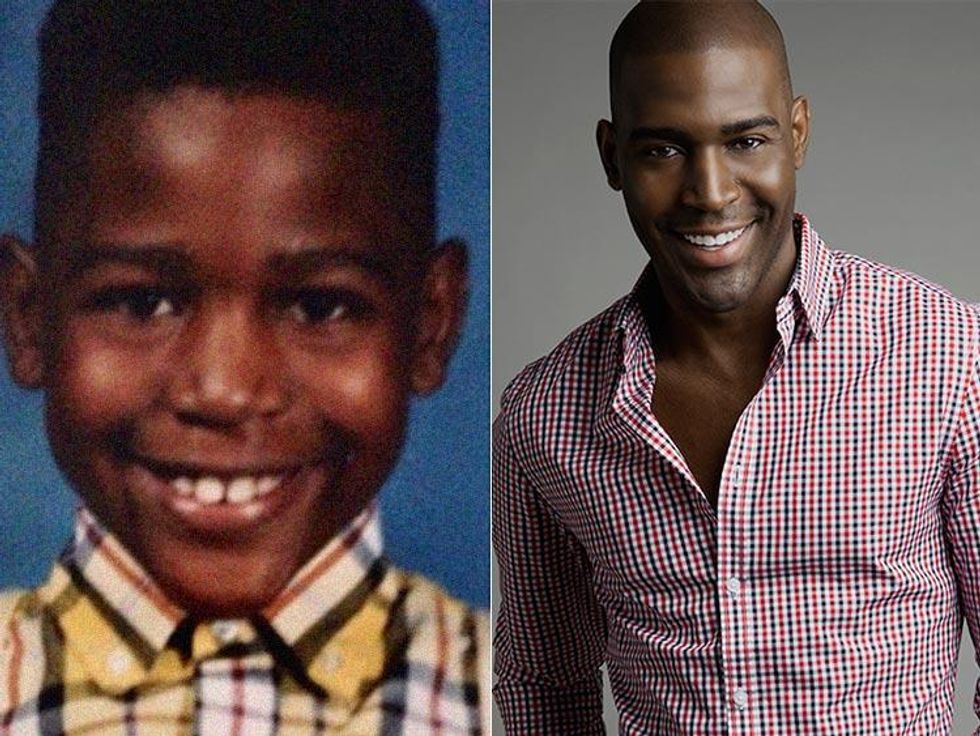

The bullying I experienced as a teen wasn't at the hands of my peers in school but within the walls of my church. I grew up in a middle-class, Jamaican-American home, where religion was a priority. On Sundays, I could always count on an evening feast with my family that would put me in a coma, but I would have to first endure a morning church service that made me want to die.

When I was 12 years old, I told my youth pastor that I liked guys as more than friends. I don't know where I mustered that courage from, but I guess the messages of "You're safe here in God's hands" and "God loves you for you" plastered on the church entrance walls made me feel like I could share my truth and be OK. The youth pastor screamed in front of the other kids, "You like what? That's disgusting. we need to pray that out of you." I was mortified. I ran out and waited by the car until my family came looking for me.

Each Sunday afterward, the teasing and downright hatred I received got worse and worse. Even on the last day I attended that youth program, I recall the youth pastor giving a special sermon on "Why gays go to hell." I felt worthless. Luckily, I had a mother, sisters, and friends who were in my corner.

When I got to college, a friend convinced me to visit their church. I was hesitant but went. The moment I entered the church, I received an abundance of love from the pastor and congregation. They accepted me. Each Sunday, feeling supported, I began to believe in God again. And the scars from bullying I received in church as a child began to heal.

KARAMO BROWN is a former cast member of MTV's The Real World and the proud father of two sons. See him on HuffPost Live and BET. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @KaramoBrown.

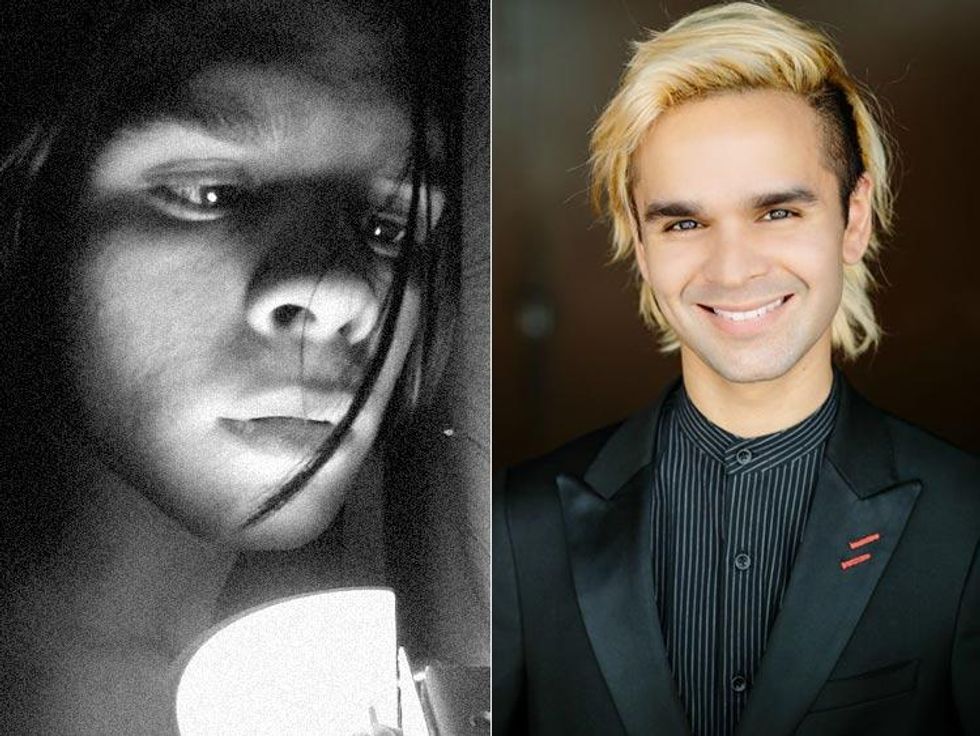

Growing up, my worst years were in middle school. I was coming to terms with my sexuality, and I was terrified of people knowing I was gay. People picked on me and took full advantage of their suspicions related to my sexuality. I was constantly put down for not fulfilling the gender roles I was expected to excel at. I wasn't good at sports. I didn't talk a certain way. My body language was not masculine enough. The music and movies I liked were too feminine. I literally had to proofread everything that came out of my mouth, and that still wasn't enough to satisfy my peers.

Bullying is verbal (and even physical) abuse, and it is incredibly hard to heal from -- it can stay with you for years and destroy your concept of yourself. I lost sight of who I was. I specifically remember being 14 years old, looking at myself in a mirror, and trying to convince myself I was straight.

For a long time, school officials, community members, teachers, and parents viewed bullying as a "normal phase" or "kids being kids" or "a part of growing up." We need to change our perception of bullying. Bullying is not normal, not acceptable, and does not have to be a part of this generation's school experience. Through Spirit Day, we can make a difference.

AMIR MOINI is a corporate relations associate at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

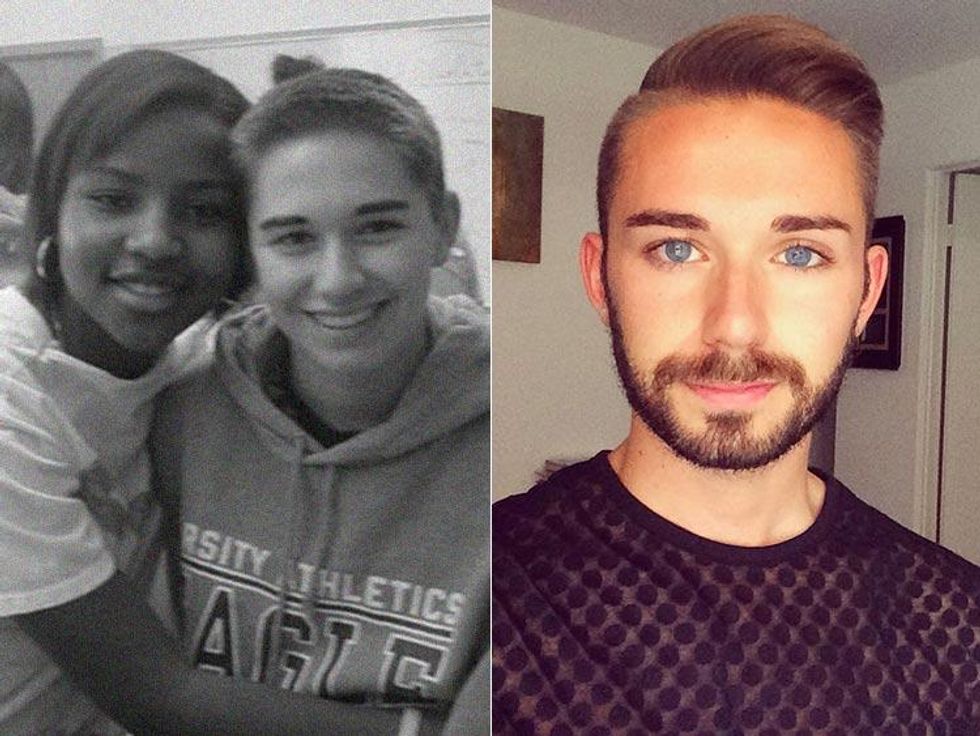

I came out as gay my senior year of high school. To my surprise, the reaction wasn't terrible. My classmates were accepting, and through friends of friends, I was able to establish a network of other queer friends in neighboring towns. With them, I felt I could finally be myself. I embraced my new identity with the fabulous fervor that happens after being pent up in a closet after 17 years.

I received a terrible wake-up call during my freshman year of college. The tight clothes, effeminate voice, and purse that I had so enthusiastically incorporated into my ensemble the summer beforehand only branded me as an outcast on my conservative campus.

In the first month, someone wrote "fag" on my door. Invitations to lunches, parties, and other social gatherings, which were mostly orchestrated by an oppressive Greek culture, dried up. Even my roommate stopped speaking to me. He left after the first semester without giving notice or saying goodbye.

However, his departure opened doors of possibilities. I had obtained a "dingle," a coveted double room that had become a single room overnight. And from that spacious stronghold, I plotted how to beat the homophobia on campus.

I joined QuEST (Questioning Established Sexual Taboos), the college's LGBT organization, a tiny group that almost disbanded due to a lack of leadership, limited funds, and poor attendance. Stepping in, I became its president by the end of my freshman year. We got to work. Our group helped facilitate a Safe Zone program that sought out allies and provided them with sensitivity training, as well as stickers that they could place on their offices and rooms. We threw a Drag Ball and invited the fraternities and sororities to come dance with us in a gender-bending party. And eventually, we launched a campaign called Gay? Fine By Me, in which hundreds of students flocked to the quad to wear T-shirts printed with this message and to chant slogans of support.

Today, I look back at that ugly word scrawled on my door as one of the most necessary experiences in my education. It forced me to confront hate, stare it down, and learn that it can be defeated. This Spirit Day, I challenge everyone to do the same.

DANIEL REYNOLDS is an editor at The Advocate. Following him on Twitter @dnlreynolds.

I was bullied every year of my teenage years. Spit on, called "f****t," shoved to the ground, and beaten up. Nobody did anything to stop it, despite my near-begging for help. I still remember the name of the worst offender, though I doubt they remember mine. I wanted to die. Being dead would have been better. [Even] my friends saw it in me. It was an odd time. LGBT equality hit a low point just after the high-visibility peaks of the early 1990s, before [becoming] resurgent again after the Bush II era.

Had I ended everything as I wished I could, I wouldn't have given a chance for things to get better. And they did, once high school was over. I've blocked most of it out, tried to seal it off in my mind, but it's in a place that isn't entirely sealed up. It's the best I can do. I'm proud of who I have become: hardworking, happy, family-minded. But a thing like that never really leaves you. Perhaps it has contributed to my drive and determination. But I don't think I'll ever lose the anger and bitterness I have for that time of my life. But do any of us, really?

TREVOR KACEDON

It's not just the last few years that I had to survive as someone who people knew of or knew about or recognized rather than to be an individual who people get to know over time like everyone else.

Starting in grade school and continuing on through high school, it really wasn't until I was in college and finally experiencing natural puberty that I truly was able to make a first impression without someone already having formed an opinion of me.

All because I was a child model and commercial actor.

I helped support my family; I earned a full one-third of our income. And I thought it was fun, even cool.

But my feelings changed the moment a certain bully cornered me and asked, rhetorically, "What makes you so special? Why are you on TV? Why'd they pick you?" I remember standing there, my back to the brick wall in the stairwell leading to McCloskey Auditorium, connecting St. Anne's School and the church, sweating, frightened, not knowing what to say.

This was 41 years ago on Long Island. I was in fifth grade, a skinny, sensitive, and effeminate 10-year-old with an "all-American" androgynous look that was my signature.

"I dunno, they just did," I stammered.

"'I dunno,'" the boy parroted me, raising his pitch mockingly, getting laughs from the gathering crowd, as he grabbed my tie with his right hand and moved his clenched left fist closer to my face. "How about I break your nose? Not gonna be on TV then, are ya, Ennis?"

My first thought: My mother is gonna kill me.

Not that I'd be in pain or bloody or that I would have to live the rest of my life with a broken nose; no, the fear that filled my mind at that exact moment was how angry my mom would get over the fact I somehow managed to have my nose broken by this overgrown escaped convict masquerading as a classmate. And he was right. A broken nose would surely cost me my career.

How many 10-year-olds do you know who've experienced panic at the thought their career might be over? I had spent six of my 10 years, pretty much as far back as I can remember, working as a model and commercial actor. And it was all about to end in a big, painful, and no doubt very costly punch.

I decided it was time for action. And that's when I came up with my plan. But I needed to time it just right.

So I stood there, defiantly, not answering his taunt, except to take my index finger and slowly tap the bully's right fist that held my clip-on tie with his G.I. Joe, kung fu grip ... and I drew an invisible line from his fingers to my nose, tapping my nose twice. As if to say, "Here it is. Give it your best shot, tough guy."

But I didn't say that. I was too busy watching his eyes change in exactly the way I imagined a bull would look if shown a red cape.

Exactly the same, I am sure. And those eyes were close enough for me to see my own petrified reflection against the wall. Our ears rang with the chant that almost always accompanied a bully -- is there a union for bully chanters, or perhaps a roadie-like experience? There should be.

"HIT HIM! HIT HIM! HIT HIM!" chanted the chanters.

He pulled my tie tighter, I watched him clench his left fist, and as it sprung from its coiled position toward my nose, I dropped like a ton of bricks and didn't look back.

I imagine I must have heard the impact of his fingers against the bricks, the scream of anger, agony, and rage as he looked at the clip-on tie still gripped tightly by his other hand, and had I turned around I'm sure I would have seen the almost certain disappointment on the faces of the chanters.

But I was focused only on the stairs that I was running down, toward the door that leads outside. A few more steps, and I'd be --

"STOP HIM!"

The chanters had turned the page from two-word repetition to two-word command, directed at anyone else in my path.

I went for the door, my hands extended to hit the bar that would spring it open. And it did not. It would not, no matter how hard I pushed, not with two boys on the other side holding that door shut.

A tall glass door, glass covering every inch except in the frame and hardware that made it operate. I stared at the four hands pressed up against that glass, and to this day I cannot recall the faces, just those hands.

I turned in panic as a bully with my tie wrapped around his bleeding fist came barreling down those same stairs I had just scooted down ... and he was headed right for me.

There wasn't any option left. I needed to escape. It wasn't just my nose that was at risk this time. I pounded on the bar to open the door, on the glass, on the frame, with my fists, with my body, and finally with my feet.

I kicked, hard ... and that's when I heard the sound that should have meant freedom.

The glass in the door shattered: some of it cracked, some fell in, some fell out, but the bottom line was: Ennis broke the door.

"ENNIS BROKE THE DOOR!" screamed the chanters.

What came next was a surprise. The bully turned and ran, and everyone followed his example. Their allies on the outside, the chanters, the bystanders, anyone and everyone cleared out so fast, you might have thought I farted.

I stood there, tieless amid the glass shards and tiny pieces, and within seconds of the foyer becoming void of children, in flew the nuns. They didn't hear the chanting, the punching of the wall, the screams to stop me, or the taunts that had started this entire ugly episode. No, what they heard was glass breaking, and what they saw was what others surely told them: Ennis broke the door.

And no, my mother was not mad, despite the call to come get me and meet with the principal. She was not mad, having avoided my nose being broken; but she still berated me for coming so close to "risking everything." Actually, it was my father who was pissed that I hadn't thrown the first punch or taken the punch and fought back or tried to or done anything other than run and break school property that we now had to pay to replace.

I share this memory for Spirit Day as a reminder of a time when I felt so despised, ridiculed, bullied, and mistreated ... just for being me.

It's sad to think there are still people in the world who feel that same way about me, even now, just for being me.

But instead of sadness, I feel so wonderful to have found love, kindness, acceptance, and good ol' simple friendship and respect, here online and out in the world. Then, and now, I'm going to be me, like it or not.

And I'm learning, slowly, what I now must do is learn how to break glass ceilings, instead of doors.

DAWN ENNIS is the news editor of The Advocate, a blogger, and an out transgender woman who in 2013 became the first to transition in a TV network newsroom. Follow her @lifeafterdawn.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.