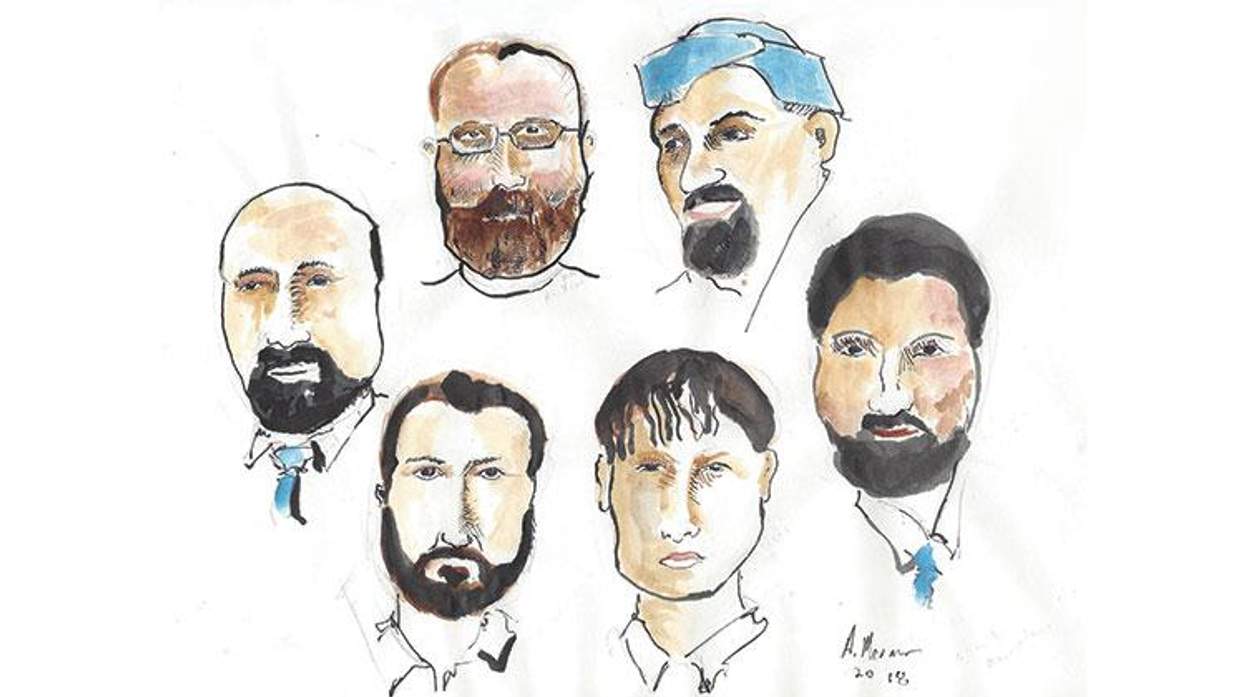

Above: Portraits of Toronto victims (clockwise from top left) Andrew Kinsman, Abdulbasir Faizi, Soroush Mahmudi, Dean Lisowick, Selim Esen, and Majeed Kayhan.

Bruce McArthur, accused of murdering men in Toronto's gay community and hiding his crimes by dismembering their bodies and burying their remains in planter boxes, is now behind bars. According to Toronto Police Service Det. Sgt. Hank Idsinga, "The city of Toronto has never seen anything like this."

McArthur, a gay landscaper who lived in Toronto for years, now faces first-degree murder charges in the deaths of six men, and just this week police said they believe they have found a seventh victim. As police scour the bottom of planters throughout the city at his clients' homes, officials expect that number to go up. But even as an accused killer is slowly meeting justice, leaders in Toronto's LGBT community question why it took so long to solve these murders that date back at least five years.

"The community did go to the media and to police when the first person went missing in 2012," says Haran Vijayanathan, executive director of the Alliance for South Asian AIDS Prevention. "But the investigation had no outcome and police said there was no evidence. Then when a white person went missing, [police] suddenly could see all these links."

Idsinga says McArthur first came up on police's radar last September, shortly after the launch of Project Prism, an investigation into the disappearance of two men: 44-year-old Selim Esen and 49-year-old Andrew Kinsman.

As it happens, Kinsman was a high-profile activist within Toronto's LGBT community and an HIV activist. Vijayanathan knew Kinsman, who disappeared in June of last year, and acknowledges his profile within the community warranted additional "noise." But he also questions if the vanishing of Esen, who was reported missing in April 2016, largely went unnoticed because he was a queer man of South Asian descent.

Police won't say what first drew their interest to McArthur. "We didn't have any evidence then to take us where we are today," says Toronto Police Service spokeswoman Meaghan Grey. Authorities say that changed January 17, at which point Project Prism turned from a missing persons investigation to a homicide case.

The Toronto Star reports police put McArthur under surveillance, then arrested him the following day after they watched him bring a young man to his apartment. Police announced that McArthur would be charged with the murder of both Esen and Kinsman, and that more charges could follow. Idsinga says police then investigated a property owned by McArthur and found skeletal remains of at least three different individuals buried at the bottom of large planters -- their identities have yet to be confirmed.

Almost immediately after the arrest, speculation arose about a past investigation, Project Houston, which surrounded the disappearance of three men between 2010 and 2012 who frequented Toronto's Gay Village. On January 29, police announced McArthur would be charged with murdering one of those individuals: 58-year-old Majeed Kayhan, reported missing in November 2012. In February, McArthur was charged with the murder of another, Skanda Navaratnam, missing since 2010. Investigations into the disappearance of Abdulbasir Faizi, also gone since 2010, remain unresolved.

Grey notes that while Project Prism and Project Houston were independent investigations, members of the detective teams overlapped, so connections between cases formed naturally. But on January 29, police announced McArthur would be charged in the deaths of two other men not part of Project Prism or Project Houston: Soroush Mahmudi, reported missing since 2015, and Dean Lisowick, a 47-year-old transient who frequented Toronto shelters and was never officially reported missing. And this week police released a photo of another man who they believe was one of McArthur's victims, asking anyone who could identify him to come forward.

Police would not discuss how investigators connected McArthur to these men, but, Idsinga notes, Lisowick was neither Middle Eastern nor South Asian, nor was he reported to be gay. So far, police have confirmed a relationship between Kinsman and McArthur, though Grey would not elaborate on exactly how long the relationship lasted. Police, including Idsinga, stressed that McArthur had not been considered a suspect or person of interest in any criminal investigation until police determined conclusively that a crime had taken place.

Neighbors of Kayhan previously told the Toronto Star he'd been living a closeted life -- living with a wife and family in one part of town, and a now-deceased partner in the Gay Village.

Vijayanathan says he suspects that police would have looked more aggressively into the disappearance of white women than a bunch of missing queer men with foreign backgrounds.

"Now we have a white homeless man nobody reported missing before he was dead," he says. "What we need to look at is how police are really treating all of our marginalized communities." Vijayanathan adds the more that comes out about McArthur's history -- he was convicted of assaulting a man with a pipe in 2003 -- the more troubling it becomes that so little suspicion fell on the white man who was allegedly using dating apps and killing gay men of color for years.

For now, McArthur remains in custody while police embark on what Idsinga characterizes as the biggest investigation in Toronto's history. In addition to the 30 properties where McArthur conducted landscaping work, where property owners have voluntarily allowed searches; police continue to search planters and other places the killer may have disposed of remains.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.