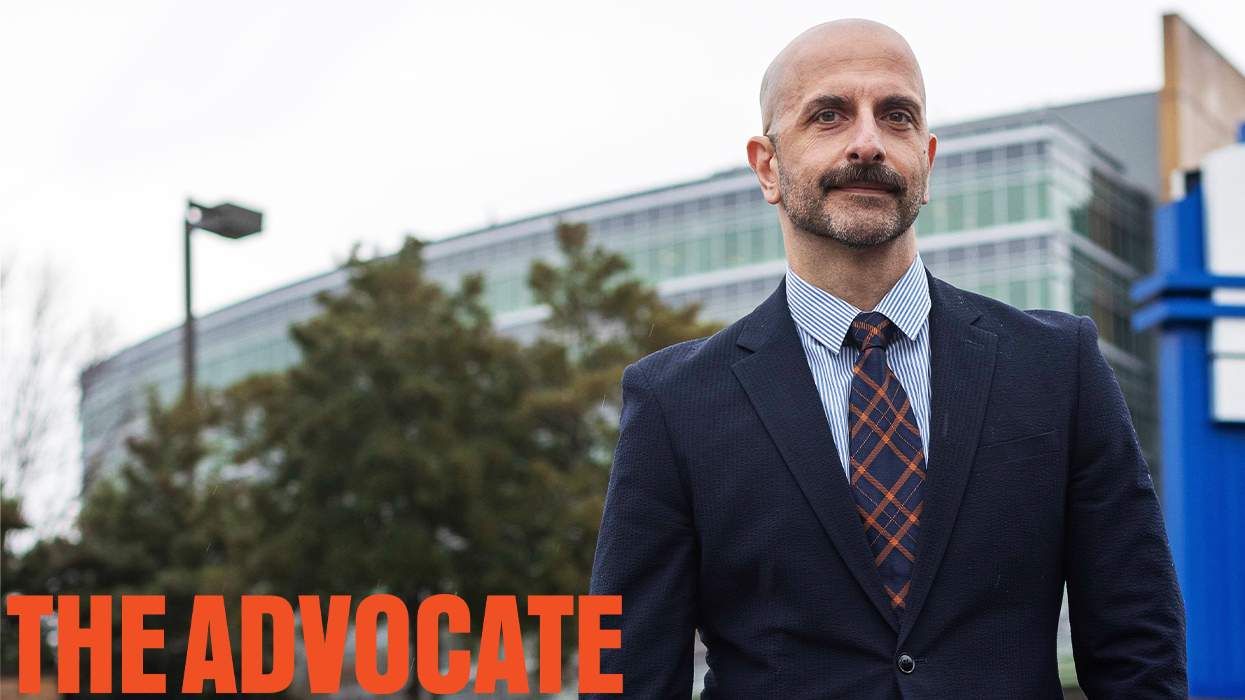

Cooking was the last thing on Thomas Romero's mind growing up in Sacramento, Calif. Always one to look for opportunities to learn, his search eventually led him to Oakland, where he lived for seven years. It was only the beginning of a long road toward culinary success.

Now the head chef at ACME, a new American bistro located in Manhattan's NoHo neighborhood, Romero is the first to tell you that his journey was anything but cliche.

The out gay chef had no interest in cooking professionally until he was 22 years old. At the time, he was pursuing a degree in nursing and hoping to have a career in hospice care. That is, until the day he went to work and realized that nursing "wasn't the type of place where I wanted to work and I didn't feel like it was for me -- as rewarding as I found the work."

"A friend of mine was working in Oakland at a restaurant, and he inspired me to consider a role in cooking," Romero remembers. "I applied for a bunch of places, and I eventually got a job at the Terrace Room in the Lake Merritt Hotel," which he explains is an extravagant art deco building that overlooks Lake Merritt. The dining room has killer panoramic views, and the hotel itself was groundbreaking in that the rooms were refurbished apartments catering to LGBTQ seniors. It was here that his love for the dining experience blossomed.

"I loved the vision and I really wanted to support it," he says of the restaurant. "One of our residents there was a 60-year-old transgender woman. It was my first exposure meeting elder LGBTQ seniors."

It became clear that cooking was his destiny, which is why Romero chose to enroll in community college. "I couldn't afford culinary school," he admits, adding that he was discouraged from going by some in the industry who argued that those who went to culinary school "couldn't cut it as well as those who learned on the job."

Romero's career breakthrough happened when he started working at Flora, a restaurant in Oakland, under chefs Rico Rivera and Yoni Levy.

"They took me under their wing and mentored me to be the best I can be," he says of Rivera and Levy. "They were massively influential in my style of cooking and my approach because they had an ease about them that I really admired. One of the first things they tried to drive home was multitasking and the ability to do four or five different projects at the same time while maintaining a quality of execution they expected of me. And it really took almost a year of working with them to get that down."

While at Flora, Romero worked directly with the grill cook. His job was to cook and create the garnishes that would go with the proteins. He ended up developing a passion for vegetable cookery.

"To this day I'd say I'm much more inventive with the way I treat vegetables in terms of how I would treat meat," he explains. "For me, meat is something you can't be really creative with, especially in terms of steaks. You can slice it and put it on a plate, but at the end of the day it's the vegetable garnish that will give it life and interest."

Romero's attention to detail forms the basis of his creative process. As the chef explains, when creating a new dish, he tends to start with necessity. For instance, the roasted asparagus he has on the menu at ACME came about because the kitchen carried a lot of excess duck fat.

"I thought, What is a way to utilize this in a way that would highlight it?" he says. "My initial idea was [to create a] duck fat glaze. So, I was thinking what could work with this sauce, and one of my cooks blurted out, 'Asparagus!' And I ran with it from there."

Another big approach for Romero is textures. "I'm a big fan of varying textures, and so when I have something to start with I'll usually try to figure out complementary textures to that."

However, what Romero prides himself on most is creating classic dishes with a modern twist. The chicken Kiev, one of the most popular dishes on the menu, is the most obvious example, he says.

"I took a classic imperial Russian dish...it's almost like a piece of fried chicken, and it's delicious and it's very satisfying, but it's also very heavy." Now, he makes it "lighter and more approachable to the modern palate."

Romero admits he has "a slightly different way of looking at things and I always try to stay true to my vision and what I think people would like. That usually starts with trying to make something I want to eat and something I enjoy, and from there, trying to figure out ways that it can be accessible to a lot of people and part of that is trying to inject a dish with a memory or a story."

One of Romero's desserts, a semolina tres leches cake, succeeds in that.

"I was told about this type of cake while I was on a date," he says. "[The date] described it to me as this type of corn bread. It's this cake that's fragrant with turmeric and aniseeds. Usually it's studded with almonds or pine nuts. And the first time I tasted it, it brought me back to this place in my childhood where we would go on fishing trips, walking through fields of wild fennel and hemlock. It was a very powerful scent memory. I want to try to have that kind of effect with my cooking, and I think a lot of chefs would say that's their ultimate goal, is to be able to have some kind of reference point, where people can see it, feel it, taste it, and have those kind of callbacks to those points in their lives."

Long term, Romero says he'd like to create an even more distinctive dining experience. "I always try to take influences from art and nature, and I'm also really interested in fashion and literary arts and cyber arts. I would like to find a way to fuse them all together in a way that's a little bit more than just a restaurant.... So, you're not just having dinner, you're not just having a theatrical experience. It's all the above.

Ploughman's Lunch

Savory Dutch Baby (Yields 2 pancakes)

3 large eggs

3/4 cup whole milk

2 tablespoons melted butter

1/2 cup bread flour

1 1/2 tablespoons cornstarch

1/8 teaspoon La Baleine fine sea salt

1/8 teaspoon freshly cracked black pepper

2 tablespoons melted butter for the pan

Toppings

3 ounces French ham or prosciutto, thinly sliced

4 ounces sharp cheddar cut into slices or crumbled

1/4 onion, sliced very thinly on a mandoline, salted to taste and seasoned with 1/4 teaspoon dill seeds cornichons (small French pickles) cut in half lengthwise, 2 per person

(Other ideas for toppings: hard-boiled eggs, apple slices, chutney)

Directions:

Preheat the oven to 400F with a 10-inch cast iron skillet inside on the uppermost shelf. Mix the dry ingredients in a small bowl. Place the eggs and milk in the jar of a blender and blend on high speed. With the motor running, pour the butter into the blender. Add all the dry ingredients at once and continue to blitz for about 30 seconds. Chill.

Working quickly, add the melted butter to the preheated pan and pour in half the batter. Return to the oven and bake for 15 to 20 minutes until the pancake is fluffy and golden brown.

Arrange the toppings over the pancake and serve immediately. You can either serve the Dutch Baby directly in the pan or transfer it to a warm plate.