Two decades after founding Vision Cathedral of Atlanta, Bishop O.C. Allen III says the church’s work is more urgent than ever. The LGBTQ-affirming Black Pentecostal congregation, which first gathered in his living room and now fills a sprawling sanctuary every Sunday, has become both a spiritual home and a civic hub at a time when queer and trans people are facing escalating political attacks across the South and the nation at large.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

On a Sunday in early October, the crowd was strikingly mixed: longtime parishioners and first-time visitors, older Black women in colorful hats, a young Asian woman with her white husband and their infant daughter, and a group of college students from Spelman and Morehouse. It was casual, exuberant, and full of motion — the kind of worship that blurs the line between ceremony and celebration. What began 20 years ago with a handful of friends has grown into a joyful, diverse congregation that claps, sings, and dances through services filled with tambourines and hugs between neighbors. Monitors above the altar flash a simple greeting: “Welcome to the Vision Experience. Invite a friend. Join the family. Let us pray with you.”

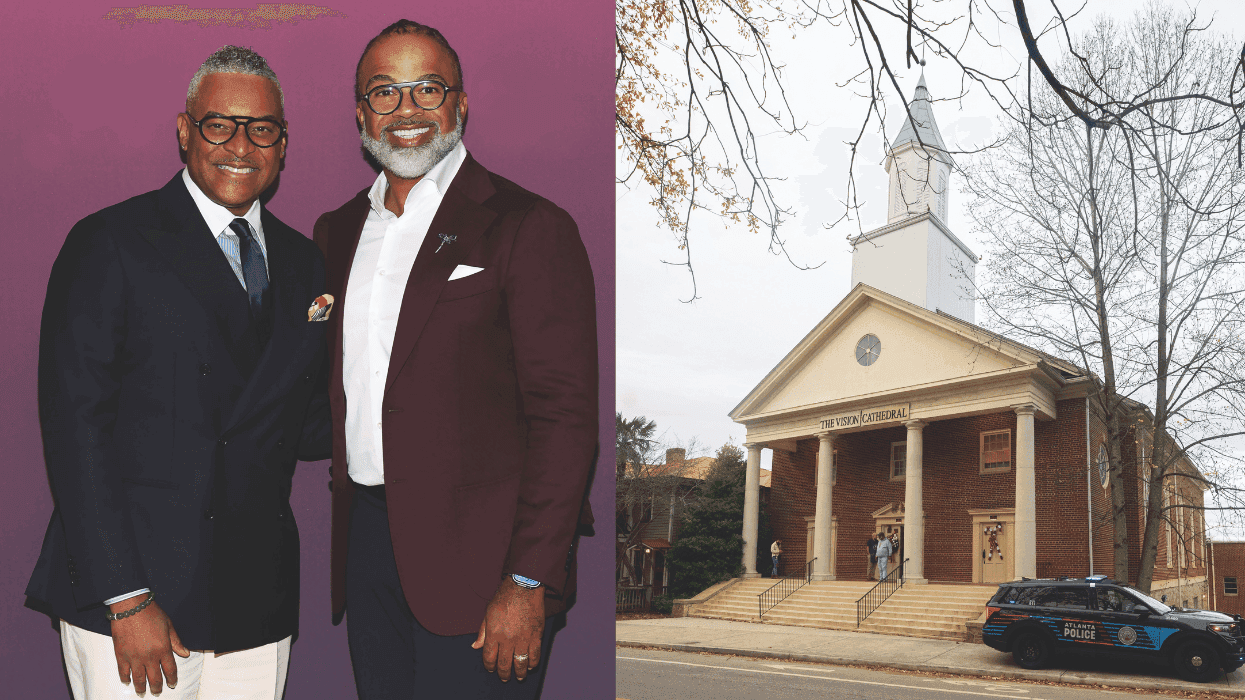

The service marked a week until Vision Cathedral’s 20th anniversary and doubled as a stop on the Human Rights Campaign’s “American Dreams” tour, led by HRC President Kelley Robinson. Robinson sat beside Allen onstage, flanked by his husband, Rashad Burgess.

When Georgia state Rep. Park Cannon rose to the pulpit to present a proclamation honoring the church’s anniversary, the crowd roared. The energy was both sacred and political — an affirmation of endurance. The congregation’s call-and-response rhythm pulsed as Allen then preached, “You can’t take my joy! Congress can’t take my joy!”

The church, which bought and renovated the former Confederate Avenue Baptist Church in 2010, now stands as one of the most visible LGBTQ-affirming faith institutions in the South. Confederate Avenue has been renamed United Avenue, and the church stands at its intersection with Ormewood Avenue. That morning, minister Toi Washington-Reynolds, a transgender member of the clergy, joined in prayer as the band played and the congregation swayed, and participated in a town hall conversation later in the service.

From the pulpit, Allen reminded worshippers that Vision Cathedral’s mission was born out of necessity. “If another table isn’t safe for you,” he told The Advocate, “you have the agency to create your own.”

The HRC visit reflected that philosophy in action. Robinson, whose Atlanta trip was part of a nationwide effort to elevate LGBTQ+ voices and reimagine advocacy, called the congregation “a living example of what resilience looks like in the South. [This is] a faith community that refuses to surrender its joy.”

For Allen, the partnership was a natural extension of his theology. “Faith without justice is empty,” he said. “When national movements meet local communities like ours, that’s when real change begins. That’s when we see faith come alive.”

He said the work ahead involves “meeting people where they are, spiritually, socially, and politically, and reminding them that the church is not a refuge from the world, it’s a force within it.”

When Allen and Burgess first began hosting small gatherings in 2005, they didn’t plan to start a church. Instead, they were looking for safety. “We didn’t use language like ‘affirming’ or ‘inclusive’ back then,” Allen said. “We just needed a moment to feel safe.”

That moment evolved into a movement. Today, Vision Cathedral’s congregation includes trans people, straight families, conservatives, and progressives worshipping together. “We have people who might look like Trump supporters sitting next to queer folks, and we’re all together. That’s the miracle,” Allen said.

The bishop credits that diversity to a shared need for belonging. “Everyone is looking for a safe space,” he said. “If we could find a way for people to feel loved and fully themselves, we’d see something powerful. Diversity brings diversity — of thought, of politics, of experience — and that makes us whole.”

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, Republicans have introduced more than 1,100 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in state legislatures since 2024, with more than 600 just in 2025. Allen believes that as anti-LGBTQ+ legislation spreads, more people are seeing the church as a path to fight back. “To live fully and authentically is the work,” he said.

Allen recalled Vision Cathedral’s early years, when protests and threats were routine. “We had protesters, death threats,” he said. “But we showed up the next Sunday and the Sunday after that. We have always known how to survive.”

His theology of joy and his choice to celebrate even in crisis were on full display during the anniversary service. “We sing, we dance, we celebrate, because that’s how we survived,” Allen said. “Our ancestors danced their way through pain and persecution. Joy is not naïve. It’s resistance.”

He added that progress always invites backlash. “When Obama became president, I told our church, ‘Get ready. It’s about to be a long 20 years,’” he said. “Progress is real, but the pendulum swings.”

Today, as President Donald Trump wields his second-term power to target marginalized communities, Allen’s words feel prescient. “Our greatness is not defined by an authoritarian,” he said. “The question is whether we’ll be students of history or of our own fear.”

Allen leads Vision Cathedral alongside husband Burgess, who parishioners affectionately call the first gentleman. Their partnership, once controversial in Pentecostal spaces, is now the cornerstone of the church’s public witness.

“This is my husband,” Allen said. “If this church isn’t for you, there are thousands of others. But if you’re here, know that existence is resistance. We don’t need rainbow flags on the walls, because the people are the flag. We walk in; that’s the parade.”

He added that the Black church itself has long been shaped by queer influence. “The entire culture of the Black church — the aesthetic, the music, the flair — is a Black gay male phenomenon,” Allen said. “The irony is that this institution, born of resistance, was shaped by people who were never fully welcomed in it.”

Allen’s sermon that morning, like much of his ministry, was about endurance — the kind that transforms survival into strength. “If it’s dark, that’s your sign: activate,” he said. “We’re not waiting for anyone to save us. We take care of each other. That’s what church is.”

That conviction defines Vision Cathedral’s next chapter. The church’s 20th anniversary is not an end point, Allen said, but a recommitment to radical welcome. “We’re proudly a church,” he said. “But we’re also unapologetically a movement. We’re here to spark transformation in faith, in politics, and in culture.”

As Vision Cathedral continues to grow in both reach and influence, Allen said success isn’t measured by numbers but by transformation. “We called it Vision because we believed our calling was to inspire everyone else’s vision,” he said. “Everyone has one. Sometimes you just need to clean your glasses. The church is the cloth.”

He paused, then added: “It’s a privilege and an honor to do this work. We’re not trying to make everyone a Christian. We’re trying to make transformers: people who change the world through love and faith, in whatever form that takes.”

This article is part of The Advocate’s Jan-Feb 2026 print issue, which hits newsstands January 27. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Apple News+, Zinio, Nook, or PressReader.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.