In 2020, I made history as the first out LGBTQ+ Iranian elected anywhere in the world. I shattered the glass ceiling as the first woman of color and only the second queer woman to serve on the West Hollywood City Council. In 2023, I broke barriers again as the first female Iranian American mayor in the United States.

I passed many people-centered, future-forward policies, but I also faced an unprecedented amount of hate: xenophobia, Islamophobia, lesbophobia, antisemitism, misogyny, and dangerous threats from factions inside and outside of the LGBTQ+ community. I endured harassment from neo-Nazis, Islamic regime operatives, fragile white liberals, and even from law enforcement leadership. The weight of being so visible while holding multiple marginalized identities eventually took its toll.

After four years of elected service on the West Hollywood City Council and two additional years on city boards and commissions, I made a conscious decision to choose myself. I stepped away from politics to reclaim my peace, my creativity, and my joy. I had spent so much time fighting for others' freedoms that I had neglected my own. I am entering a softer, more feminine era of my life, one rooted in healing, travel, and soulful experience.

I've always believed that being present in places where we are not always welcome is a powerful form of advocacy. I have been active and made my mark in many such places. But now, my advocacy has a different tone.

It is not loud or legislative. It is grounded, embodied, and deeply personal. It is about taking up space on my terms.

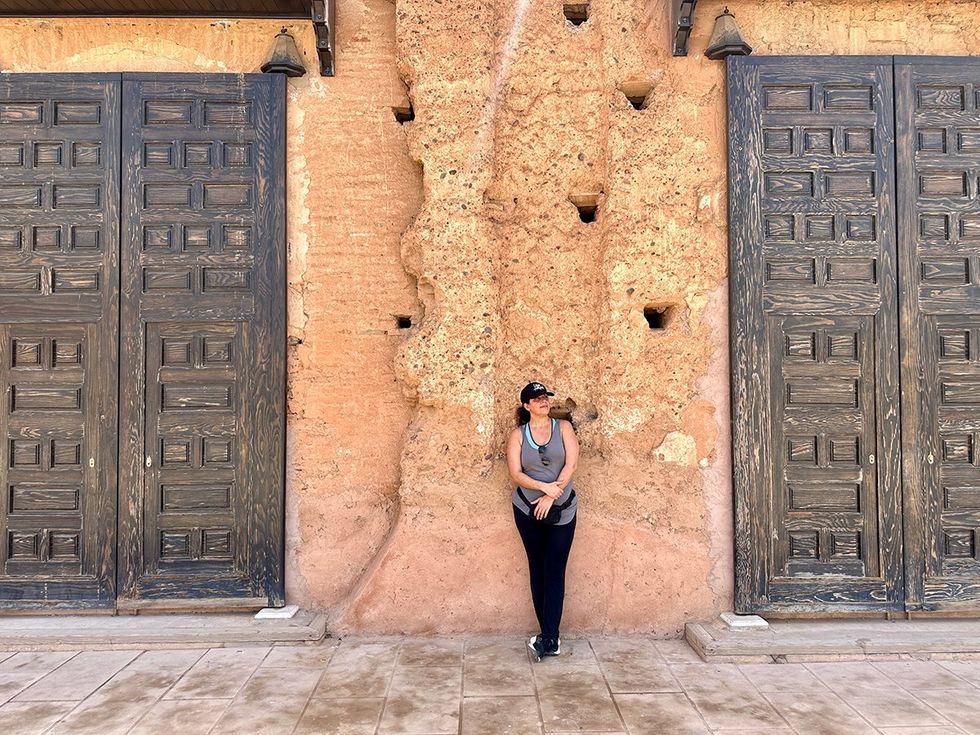

Sepi Shyne

Courtesy Author

My first destination on this journey was Marrakesh, Morocco. Marrakesh is a city I had long yearned to visit but deeply feared. As a woman, as a queer person, and as a liberal Muslim-born Iranian, I carried layers of anxiety about traveling to a predominantly Muslim country where LGBTQ+ people are criminalized.

To create a layer of safety, I traveled with my business partner, a fellow LGBTQ+ woman of color. Our journey included a layover at Istanbul Airport en route to Marrakesh. Though we never left the airport, being physically that close to Iran for the first time since I was five stirred complex emotions. Part of me felt a bittersweet proximity to my homeland. Another part carried unease, given Turkey's role in supporting Azerbaijan's 2020 invasion of Artsakh. This conflict killed thousands of Armenians and displaced over 110,000 people. Even in transit, my intersectional identities — queer, Iranian, and attuned to geopolitics — remained deeply present with me.

Souk el Attarine, Medina of Marrakesh, Morocco

Courtesy Author

From the bustling, disorienting energy of Istanbul Airport, we boarded our connecting flight to Marrakesh. As we crossed into African airspace, I felt a grounded calm energy. When we got off the flight, my first greeting came from a friendly black airport cat who was an omen of the unexpected softness I would encounter throughout Morocco.

At customs, I had my first direct encounter with Morocco's complex cultural stance toward LGBTQ+ people. A male officer flirtatiously asked if I was traveling alone. When I pointed to my business partner, he smiled and asked pointedly, "Is that your friend or your best friend?" His question brought back memories of the early 2000s, when my own family introduced my then-wife as my "friend" at gatherings. Today, my family fully embraces my identity. I hadn't expected a Marrakesh customs officer to have any awareness of queer relational dynamics. The fact that he acknowledged the possibility at all surprised me. It was not openness by Western standards, but it wasn't complete denial either. I felt some of my previous fears around visiting dissolve.

As we drove to our hotel, I noticed a thriving scooter culture, with women riding confidently through the streets, and even glimpsed what appeared to be a female queer couple riding together. Seeing them reminded me that visibility exists, even where legality does not.

We stayed at the breathtaking Jnane Tamsna, a luxury boutique hotel owned by Meryanne Loum-Martin, the first Black female hotelier in Morocco. Spread across lush regenerative gardens, Jnane Tamsna became a sanctuary for us. Over farm-to-table meals and Moroccan mint tea, Meryanne shared her deep allyship for our community. Her presence reminded me that meaningful connections and advocacy can thrive even in places with legal and cultural complexities.

Memorial for Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé in Jardin Majorelle, Marrakesh, Morocco

Courtesy Author

One of the most beautiful places I visited in Marrakesh is the Jardin Majorelle, the garden gifted to Morocco by Yves Saint Laurent and his partner, Pierre Bergé. Walking its sacred, color-drenched paths, I thought about how much they had poured into this land. Their love helped preserve a space that became iconic. Their presence helped turn Marrakesh into an international destination of beauty and art.

And yet, their love is still illegal in the very country that honors their names in plaques and guidebooks.

As queer people, especially queer people of color, we often give everything and still get erased. We create art, neighborhoods, culture, and safety. And others come to consume what we build, without offering protection or acknowledgment in return. I've seen it growing up in California. Queer enclaves become trendy, but over time, the very people who made those places safe and vibrant are pushed out, either socially or economically. Even in cities with LGBTQ+ leadership, state law often prevents us from giving our communities the protections or funding they genuinely deserve.

Standing at the memorial to Yves and Pierre, I felt the grief of that imbalance. We are allowed to be admired, but not safeguarded. Loved in memory, but not in life. That's not enough. Not anymore.

Slat El-Azama Synogogue, Marrakesh, Morocco

Courtesy Author

Later, in the historic Jewish Quarter, our guide told us that during World War II, when Morocco was under Nazi-aligned Vichy rule, King Mohammed V refused to hand over Moroccan Jews. He reportedly said, "There are no Jews in Morocco. There are only subjects." I felt moved learning that a Muslim monarch, in a moment of global fascism, protected Jewish lives. He chose courage over compliance.

As a queer Iranian woman of Muslim heritage, I know what it feels like to be expected to pick a side. Right now, with the recent war between Israel and Iran and deepening fractures across the globe, it feels like the world is asking us all to flatten ourselves into absolutes.

But this story reminded me that nuance has always existed. Compassion has always been possible. Even in places and from people we least expect it.

It gave me real hope for a new way forward for humanity.

Another moment that shifted something in me happened at the Bahia Palace. The space is opulent and historic, but I found myself contemplating the layers of power, patriarchy, and unspoken relationships that shaped these spaces. I found myself wondering if any of the sultan's many wives had been lovers. If there were stories behind those doors that will never be recorded. I asked our guide. He looked surprised, then nodded. "It's possible," he said. I was reminded of the immense privilege that I have enjoyed as an out Iranian American in California, not having to be one of many wives to a man while secretly in love with one or more of the others.

I carried that thought with me into our final night in Marrakesh, where we were invited to dinner with Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first female head of state in Africa. Sitting among powerful women from across the continent, I realized I still belonged in that space, not as an elected official, but as a woman who leads differently now. I don't need a title to make an impact. I lead by moving, healing, and loving. I didn't expect Marrakesh to change me, but it did. The experiences unraveled layers I had not had access to. I remembered what still matters most.

Sepi Shyne in Badii Palace, Marrakesh, Morocco

Courtesy Author

I'm still devoted to justice. I still believe in visibility. But I no longer think I have to sacrifice my well-being as proof of my commitment to collective liberation. I've given so much to movements, to my city, to causes. And I'm proud of that. Now I am choosing to protect my peace, my body, and my joy.

I'm not giving up on leadership. I'm just changing how I lead. From now on, I will lead with softness and presence. As I continue my travels, I carry all of my identities with me: queer, Iranian, immigrant, woman, healer, and leader. My presence in these spaces, without apology, without hiding, is itself an act of joyful resistance and of radiant freedom.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Advocate.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, equalpride.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.