When you’re raised in South Florida, distance is just something you get used to.

The land goes on forever, flat as paper. It's no wonder flat-earthers still exist. In the middle of nowhere, you can watch the world stretch to the edge of your vision like the surface of some endless ocean. The entire landscape feels like it was leveled by a natural disaster ages ago, and nothing ever grew back. Nothing but parking lots, shopping plazas, and gated communities, each trying to out-grandiose the last. Strip malls sprouting where forests once were. Big-box stores risen like temples to consumerism. It felt like all of South Florida had been bulldozed, paved over, and then forgotten in the sun.

The school I attended was over thirty miles from my house. Before I could drive, my mom would drop me at a nearby school where a yellow bus picked up me and a few other scattered kids, delivering us to the Tri-Rail station. That was where the real journey began. Every morning, we waited with a small crowd of students and worn-out commuters, baking in the pale Florida sun. I'd stand far off to the side of the platform, puffing on the cigarette I'd swiped from my mom's pack.

When the train finally pulled in with a hiss, I chose a window seat, pressed my head against the glass, and put on my headphones. I let my long, oily hair hide my face, trying to disappear into the music. The soundtrack changed depending on my mood. The Locust, Nine Inch Nails, Tool. But the ritual was the same: find the right track and loop it while the familiar world slipped past. The ride to the West Palm Beach stop took forty-five minutes. Long enough for an album, long enough to watch the landscape shift from parking lots to overgrown fields and sun-bleached "Coming Soon" signs that had been rotting for years.

Even after I got my driver's license, the endlessness didn't stop. Everything in South Florida felt far away. It was always a long drive: To hang out with a friend, see a movie, go to a show, or meet a boy I'd flirted with online. Palm trees blurred past, broken up only by gas stations, shopping centers, and identical subdivisions that mirrored one another in every detail. Even speeding down the highway, it never felt like I was moving fast enough to escape the sprawl.

I think maybe that has something to do with being queer.

When you're a teenager, everything already feels like it stretches on forever. You're always waiting - for your body to change, for the world to notice you, for life to begin. But there's a different kind of waiting when you're a queer teenager. It burrows deep into your chest and stays there.

It's a longing that becomes a vacuum.

And if distance is a geographical fact of life in South Florida, longing is its emotional twin.

I often felt an ache for something I couldn't name - love, connection, recognition I feared wasn't meant for someone like me. I knew other gay kids at school. I even saw a few couples orbiting each other like rare moons in some forbidden solar system. But for me, even surrounded by people, I felt removed. Like the thing I wanted most was always happening somewhere else.

I got so used to the mechanics of distance. I adapted so well to waiting that I started believing the waiting was the point. Queer longing isn't just a crush; it's a practice. A slow burn that builds for years. You become a master at secrecy. You learn to want in private. To dream quietly. To hope without proof.

And even in a crowd, you still feel like you're standing alone at the edge of some vast, flat world, waiting for someone to find you.

Throughout my life, I've met more queer people than I can count who know that waiting. We swap stories in smoky dorm rooms over beers at all hours of the night, on long walks in suburban neighborhoods, in corners of loud parties and quiet kitchens. There's an unspoken recognition when someone describes coming of age in that liminal space of longing.

I've heard the stories: the terror of parents finding out, or a friend stumbling across a secret note. A chat window left open, or a poorly timed glance in gym class. And the fallout that followed, from screaming and silence, to moving or being thrown out. So many had to leave everything behind to survive, to start over somewhere else, to find their tribe.

And I've also heard the stories that ended too soon.

Thoughtful and sensitive kids who couldn't bear the stretch between wanting and finding. Some who stayed trapped too long in that nowhere-space and lost the fight against hopelessness. That's what kills so many of us. Not being queer, but being alone. Queer and invisible, convinced there's no one else like you out there in the flat, featureless world.

I would tell any young person reading this that the longing never entirely disappears. But it can become a gift.

I've painted most of my life. I was fortunate enough to attend a middle and high school that offered me an immeasurable wealth of experience and study in the arts. Inspiring teachers who gave me room to question, explore, and hide when I needed to. They gave me the tools to create and the vocabulary to express myself through the things I made. Looking back, I owe so much of my survival to the teachers who saw me when I was still too afraid to see myself. I found sanctuary in charcoal, photography, and paint. The teachers who encouraged me didn't just teach art; they also inspired me. They taught me that my voice mattered.

That I mattered.

And yet now, across the country, those very teachers, along with librarians, counselors, and supportive parents, are being silenced, threatened, and fired. They're being targeted for doing precisely what saved so many of us: offering queer kids a lifeline. Creating and holding space. Telling them they are not wrong. Not broken. Not alone.

In a time when fear is being legislated and cruelty masked as protection, the very people who once helped pull us back from the brink are being pushed out. And that's the terrifying irony: because it's those people who save us from being swallowed by the vast, sprawling despair.

And we need them now more than ever.

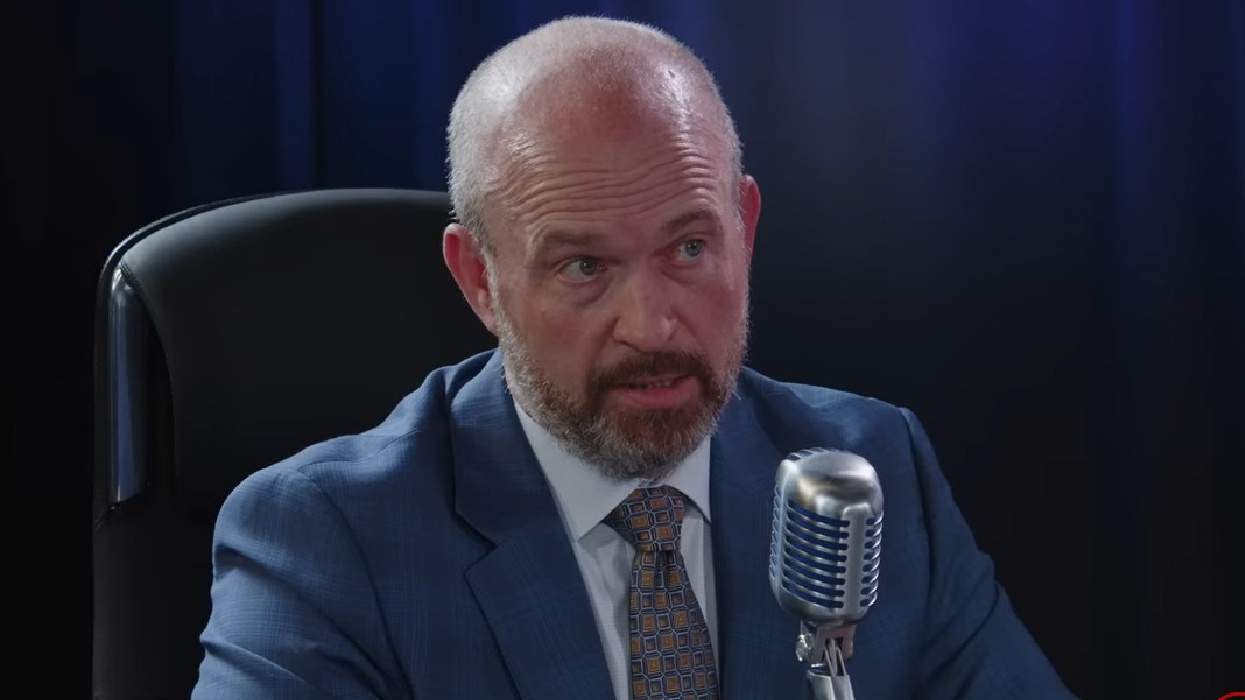

Matt Lifson is a visual artist, writer, and educator. His work explores themes of longing, isolation, and desire within queer contexts.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Advocate.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, equalpride.