While the L may kick off the LGBTQ+ moniker, in recent years it has become inexplicably fraught. As our understanding and rejection of the constructs around gender continue to become richer and more complex and the TERFs get louder and more histrionic some corners of our community have begun looking sideways at the proud Ls our midst. But is that fair? Certainly the Gs aren’t facing the same scrutiny. In times like these self-reflection is required. But the question remains: Is being a lesbian innately problematic?

For me, Mey Rude, a 37-year-old trans lesbian who has been working in lesbian media for a decade, coming out as a lesbian meant freedom, joy, and self-acceptance, but for many these days it seems to mean policing, transphobia, and division. We're not going to stand for that.

I have a lot of strong opinions on the word, identity, and community that is "lesbian." I'm not about to watch my favorite word in the world get dragged through the mud.

Together with my coworker Tracy E. Gilchrist, a cis Gen X lesbian whose worked in LGBTQ+ media since 1999, we sat down to discuss what being a lesbian means to us, and why we want to fight back against recent negativity around the term. What follows is our conversation about the word aka: why we love being lesbians and are not about to let the TERFs take that from us.

Why do you identify as a Lesbian?

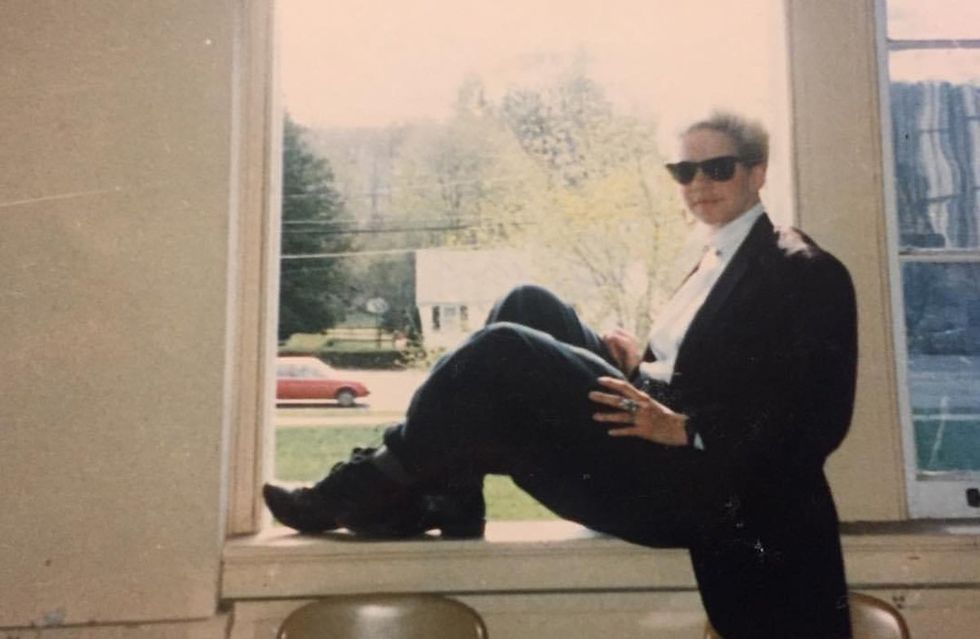

Tracy Gilchrist & Mey Rude

Tracy: It wasn’t a straight line (so to speak) to identifying as a lesbian. Though I had a girlfriend during my junior year of high school, we eschewed labels. She called it “aesthetic appreciation.” Exhibiting some internalized lesbophobia, I wanted to distance myself from the Birkenstock-clad, unshaven man-hating lesbians that were the stereotype and who were roundly mocked in my high school. The only out lesbian I was aware of at the time was Billie Jean King, who was forced out of the closet and derided by the media, and sadly, people in my family, for being a lesbian.

Because I’d dated boys before and after my first love, I identified as bisexual for a few years. I realized in my early 20s after having fallen headlong for two other women that although I might find a guy physically attractive, I had zero interest in an emotional connection beyond friendships.

Mey: This is exactly how I feel. While I still might find men attractive, and I fondly remember some of my sexual encounters with men and can conceive of a world where I'd do it again for fun, I really have no desire to do anything more. And for me, that means lesbianism.

Tracy: It's funny. I can find men attractive, but I don't fondly remember any physical interactions with men. This is perhaps something for another conversation, but I've begun to feel like I'm something of a demisexual as well.

In the early 1990s I used gay more than I did lesbian. That was couched in some internal lesbophobia too. I’ve always had a deep rapport with gay men, and the word “gay” connoted “fun” to me. The word lesbian always sounded so serious and clinical. It’s also identity under the umbrella that requires an article. I am “a lesbian” as opposed to, “I’m gay. I’m bisexual.” There’s an inherent othering in its application.

Mey: I didn't always identify as a lesbian either. When I first came out as a trans woman, I came out as a lesbian at the same time, but in the following years as I explored womanhood, I also explored my sexuality and identified as bisexual for a time and had some experiences with men.

However, those experiences only reaffirmed my identity as a lesbian, something I stand proudly in today.

Tracy: As a California transplant from liberal Connecticut who worked in the theater and then LGBTQ+ media, I’ve managed to live in a safety bubble for much of my life. The word used the most to mock and diminish me when I was young was “queer.” And it wasn’t strangers who used it to hurt me. Those were people who were close to me in some way. One of those people was a counselor at my Girl Scout camp I had a crush on when I was 12. I must have hugged her for too long or paid too much attention to her. She used the word queer to signal for me to back off. Camp had been a safe space for me. I was unaware of my sexual identity to that point and I was devastated. Today, I use the word queer liberally as an umbrella for LGBTQ+ people. It’s likely the word I use most throughout the day, and it’s part of a taxonomy of how I describe myself now. But lesbian honors my love of women. It feels the most correct.

What does 'Lesbian' mean to you?

Whitney Mixter attends the Dinah on The Real L Word

Courtesy of Showtime

Tracy: Lesbian is a sexual identity, a political and historical identity, and a sensibility. Simply, it means that I love, have loved women. It’s not to say that I couldn’t love someone whose identity is more expansive, but the word for me is couched in a lifelong love and reverence for women.

It’s also a nod to my history to call myself a lesbian. I know the word is weighted with stereotypes of having too many cats and belting the Indigo Girls on a road trip to The Dinah (I identify with both of these stereotypes), and less favorable notions of humorless shut-ins. My decision to identify as a lesbian honors those who came before me who loved other women behind closed doors and in the shadows, those who risked their lives and livelihood for the right to honor their truest selves.

Mey: For me, being a lesbian means I'm a woman who loves other women. I don't need it to be much more complicated than that. I don't need to put a bunch of rules and asterisks in order to make room for the existence of trans people and fluidity, the lesbian umbrella is big enough to fit us all.

Tracy: I love that you said this part out loud, because, clearly, I feel like I have to qualify it. I'm Generation X. In some ways, I feel like I'm about to be put out to pasture, so when I'm answering a question, I want to be sure I'm as thorough as possible. But it is as simple as you've made it.

Like a gay or camp sensibility, there’s also a lesbian sensibility. While much of what I love falls into a camp sensibility, the lesbian sensibility feels like a shorthand with other lesbians. For me that’s hearing Tracy Chapman’s eponymous first album and just having a feeling or a knowing, or watching Kristen Stewart and Katy O’Brian in Love Lies Bleeding at an early screening with a lot of queer women in the audience and having that shared experience. Anecdotally, last fall, I invited a gay male friend to be my guest at Brandi Carlile and Friends at the Hollywood Bowl. Late in the evening, they turned around a set to reveal Brandi seated next to Joni Mitchell in a chair akin to a throne. Annie Lennox was on the other side. Next to her were lesbian icons Wendy & Lisa and the great queer Americana musician Allison Russell. Partway through what was like a fireside sing-along, Russell picked up her clarinet and began to play. My friend’s mouth was agape. He didn’t know what to make of this utterly sincere moment of communion under the stars. I thought, “Oh, that’s right. He’s never been immersed in lesbian camp culture.”

Mey: I LOVE LOVE LOVE what you said about lesbian camp. I talk to my friends about that all the time. It's such a wonderful way to describe the specific culture that comes from being a lesbian and the joy we get from connecting.

Here in LA, we have a professional women's soccer team called Angel City Football club, and my fiancee and I are season ticket holders. Whenever we go to a game it feels like we're coming home. There are lesbian couples everywhere, queer kids running around, celesbians like Hayley Kiyoko and Lily Singh and lesbian icons like Jane Fonda attend games, and every man is wearing a shirt celebrating women's sports. It's absurd how over the top it is, but for a lesbian, it's home.

Tracy: Now you've convinced me I need to attend one of these matches! It sounds like nirvana.

What associations do you have with the word?

Tracy: My earliest associations of the word were of the butch couple at our church who became a part of my mother’s friend group. One of them worked for UPS. They had a blended family of kids from marriages to men. I think for a long time I thought a lesbian had to present as butch. While there are those who’ve labeled me as butch in the past, it doesn’t feel like me. I’m no high femme, but I’ve always felt like I was just myself on a spectrum of gender presentation.

There was a lesbian bar in Hartford in the ’80s called Commercial Street. In my late teens, and without an ID, I would sometimes go alone to be among other like-minded women, to feel their energy. I was in my New Wave phase with two-toned hair akin to Annie Lennox’s, and I remember dancing to Erasure’s “A Little Respect” with my spiky hair in a butcher-block coat I’d bought from a funky clothing store called Pelican in downtown Hartford. I associate that bar and that moment in time with the word.

It’s hard to not conflate “lesbian” with the stereotypes I’d become aware of — the health-food store separatists on farms eating tempeh and bulgar. When I was first beginning to understand that there was a world of lesbians who somehow found each other, lesbian connoted those women who listened to records on the Olivia label like Cris Williamson and Meg Christian.

Mey: For me as a trans woman lesbian who grew up essentially as a boy wishing she could be a woman, I thought lesbians were the best thing in the world. I was nine years old when the WNBA started and ten when Ellen came out, and I remember thinking that women with short hair and confidence around other women were the coolest thing I had ever seen.

My mom loved Ellen. I remember watching her sitcom as a kid, and I definitely saw her as a role model. My parents also knew I was queer from a young age and so they talked positively about LGBTQ+ pop culture figures and shows like Ellen and Will & Grace. She introduced me to the Indigo Girls at a young age, and we watched Rosie O'Donnell's talk show every day. So that only added to my view of lesbians as arbiters of coolness and likability.

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images for Coachella

Tracy: Lesbian was the opposite of cool when I was coming into my identity. Decades into my being out, The L Word helped change my relationship to the word. I was still in Connecticut dreaming of Hollywood anyway, and then these beautiful women who moved in lesbian spaces and defined a culture helped to change the way I saw myself. Of course, The L Word was imperfect, but seeing myself in this friend group of (mostly lesbians) validated me. It’s only in the past few years that I’ve begun to synthesize the shift in my attitude toward my own identity with the rise of lesbian characters in media and in life.

When I was coming out, I had a sense of superiority about my queerness — like I had discovered something secret and sacred that was not for the masses. It was my armor, a survival mechanism against feeling othered. If I were in my teens or early 20s and someone like Renee Rapp, in all of her raw talent and cool confidence, had proudly declared they were a lesbian, it would have mattered. Now I like to think I now associate the word with fearless women who know what they want.

Mey: I had female friends who would joke about me before I came out as trans that I was a "male lesbian," and secretly, I loved it. That made me feel special, like I was allowed in the club, and not only that, but I was seen as being equal to the cool girl with the buzz cut and leather jacket smoking in the corner. So when I realized that I could actually be a lesbian, it changed my life. I still find myself being amazed that I get to be a lesbian nearly every day. I love it, and I don't think I'll ever get tired of using the word for myself.

Some people argue that the word Lesbian has been co-opted by TERFS and other exclusionary and hateful groups, what do you think about that?

Shutterstock

Tracy: In 2017, before Ellen DeGeneres’s social fall, I wrote a personal essay about how her coming out in life and on TV impacted me 20 years earlier. I opined about the loss of queer spaces, specifically The Readers Feast, a gay-owned bookstore and cafe in Hartford, Conn., where I worked on and off in the ’90s. I scanned the comments sometime after it was published to find one from a trans woman who wrote of feeling unwelcome in lesbian spaces back then. I had to honor that my experience of missing some of those spaces was not universal for all queer women. While I’d like to think that acceptance across a gender and sexuality spectrum has improved significantly since my early days of romping around lesbian bars, I do live in a bubble. I work for the company that owns The Advocate and Out. I find myself advocating for expansive identities even among other queer people in Los Angeles. There are plenty of cis straight people as well as cis queer people who aren’t as progressive as they should be with understanding and welcoming trans and nonbinary folks into all spaces.

We must acknowledge a history of trans-exclusionary lesbians and spaces like the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, which shut down in 2015 after 40 years. It’s “women-born-women” only policy never evolved, and by the time it shut down, artists who’d performed there for years,like the Indigo Girls, began declining the invitation to perform. The festival excluded itself out of what could have been a life-changing event for generations of queer people.

Mey: Nowadays, TERFS make me prouder than ever to be a lesbian. The TERF segment of lesbians is getting further and further away from anything that resembles real lesbians every day. They spout misogyny, bioessentialism, and patriarchal bullshit everyday in their fight to kick trans women out, and I know that that is not lesbianism.

Shutterstock

Tracy: Even within the past few years, there is a contingent of lesbians who have spearheaded a hate campaign against trans people. AfterEllen, once a safe haven for queer women obsessed with pop culture, was co-opted by trans-hating queer women who peddled misinformation and fear-mongering. Those people should be called out and held accountable for their hateful beliefs, as should cis straight women and cis men of varying sexual identities who contribute to fear mongering of trans people.

Mey: As a trans lesbian, I have been that person who felt excluded in lesbian spaces, and AfterEllen was one that I specifically felt alienated by as a lesbian pop culture journalist. The site never published articles or essays by trans women, and I noticed that.

I've also been in a few public lesbian spaces where I felt excluded, but honestly, that often came from bisexual and otherwise queer women, not just lesbians. I don't think that cissexism or ciscentric thinking are exclusive to lesbians.

I honestly had a lot of very negative experiences with people identifying as pansexual who would tell me things like "I'm into men, women, and trans people," despite me telling them I was a woman. Those types of comments made me want to dig into my lesbian identity, because in that identity I felt like my womanhood was being honored and centered.

Tracy: I agree that cissexism and ciscentric thinking aren't exclusive to lesbians. There's something a bit sexist in that notion. The thinking that lesbian = TERF also erases the fact that there are trans folks who are lesbians.

Mey: I know as a trans lesbian my lesbian community is better than they will ever have, and it makes me proud. The lesbians I know in real life and online love me and find me desirable and wouldn't want to have a lesbian space without me. And I know that the majority of lesbians are the same way.

Others say that "lesbian" is a very exclusive club that can't include people who have slept with or been attracted to any men (including trans men) or non-women, and also can't include anyone whose gender is more complicated than "woman." How do you feel about that?

Luiz Gustavo F Rossi/Shutterstock

Tracy: I’ve never heard this exclusionary idea.I suppose if you want to be a part of the smallest club on the planet then this works. It significantly shrinks the dating pool, however. It’s an ageist and privileged regarding older generations of women and those in unsafe spaces who were socialized to be with men, expected to be with men, and in some cases forced to be with men. It assumes a certain amount of safety to never have to actively mask your lesbian identity. There are people throughout the world today whose safety is in jeopardy for their queerness.

Mey: I always want there to be more lesbians, and if sleeping with a man, or enjoying having sex with a man, or even dating a trans man or having your partner come out as trans means you're not a lesbian, that means most of us will be kicked out.

Being a lesbian is about fighting against the rules of what women are supposed to be. It's not supposed to be about policing every feelling of attraction or sexual arousal you feel. Coming out as a lesbian should free you up to explore your sexuality.

Tracy: “Gold Star” was the term people used to identify a lesbian who’d never slept with a man. I never used it. I wasn’t a part of that club, nor did I think it mattered to be a part of it. Still, it was a badge of honor for some. But it erased the journey of coming into one’s true self, whatever that looks like.

If I were to apply this rubric to my identity, then I’m bisexual. But then, I’ve only ever loved women, so how do the people who believe in this exclusivity square someone like me with emotional fidelity to women with the fact that I’ve experimented sexually along the way? This idea reduces the whole act of being with someone down to a sex act. It’s absurd in its narrow-mindedness.

Mey: I also want to say, from a practical standpoint, there are a ton of trans men, trans mascs, and nonbinary people who are important, deeply-embedded members of the lesbian community and it doesn't make sense to kick them out just because they finally feel comfortable in their skin.

It also wouldn't do any good for the lesbian community. We'd just be kicking out some of the people who make our community what it is. And with the way people's sexuality and gender can change over time, it's not even possible to tell if someone will become nonbinary or transmasculine in the future.

When you hear a person say the word "lesbian" is "bad" or "gross" how do you feel?

Courtesy of A24

Tracy: It seems impossible to conceive of a time before Kristen Stewart basqued in her queer identity, the object of so many who desire her and the envy of those who long exude an ounce of her coolness. I interviewed Stewart on the set of Happiest Season in 2020. She was frank about her internalized lesbophobia when she was young. The woman who declared, “I’m like soooo gay, dude,” in her Saturday Night Live monologue, shared with me that it would have been meaningful to her had breezy romantic comedies about women who loved women existed when she was younger.

"I didn't want to be called a lesbo. And I didn't want to be that weird, gross, 'dykey' girl. And that sucks. It's terrible. But I was always really attracted to, sort of, weirdness and otherness. I would've loved to have had more examples of that not being ridiculed and a point of scrutiny. Yeah, that would've been awesome," Stewart said at the time.

Stewart is bisexual, but her resistance specifically to the words “lesbo” and the “dykey” is relatable for many. It was her use of the words “weird” and “gross” that struck me the most, because she was on to something. Lesbians, women whose identity is free from men for sexual and or romantic pleasure are perceived as freaks by the virtue of the fact that we don’t orbit around men. I’m reminded of the “Cool Girl” speech from Gone Girl or the “pick me” girls whose identities are steeped in acceptance in cis-hetero male circles. So much resistance to the word “lesbian” is steeped in misogyny.

Mey: I think sometimes young queer people get caught up in trying to control the only thing they can in this chaotic world, and that thing is their own labels. And so that leads to people making very strong associations with words (whether fair or not) and treating labels as if they are in opposition to each other, rather than complimentary points on a spectrum.

They want to be able to say "this is exactly who I am," and in a world where labels mean everything, many people feel they have to be pedantic and prescriptive when it comes to language and identity. And this leads to people taking extreme viewpoints of words like "lesbian" that were created before Queer Theory was even an established field of study.

Tracy: A few years ago, I moderated a panel for a queer femme attracted to masculine-of-center queer people whose project did not portray lesbians in a great light (she appeared under the impression that two lesbian femmes can’t have great sex together). We each shared our pronouns and how we ID. She visibly bristled when I used the word “lesbian” to describe myself. I continued with the job I was there to do and asked thoughtful questions, leaning into the more progressive parts of her project. I think I won her over. And I hope I shattered some of her preconceptions about lesbians.

It’s been nearly 40 years since my first girlfriend, and I’m still unpacking the words I use to identify myself. I’ve evolved from earliest understandings of what a lesbian is to proudly own it. I’m excited that the “cool girl” now includes lesbians like Renee Rapp, Hayley Kiyoko, Lena Waithe, and Jodie Foster.

Mey: I think there's much more freedom to be found if we can accept that labels aren't meant to police us and are only made to connect us.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.