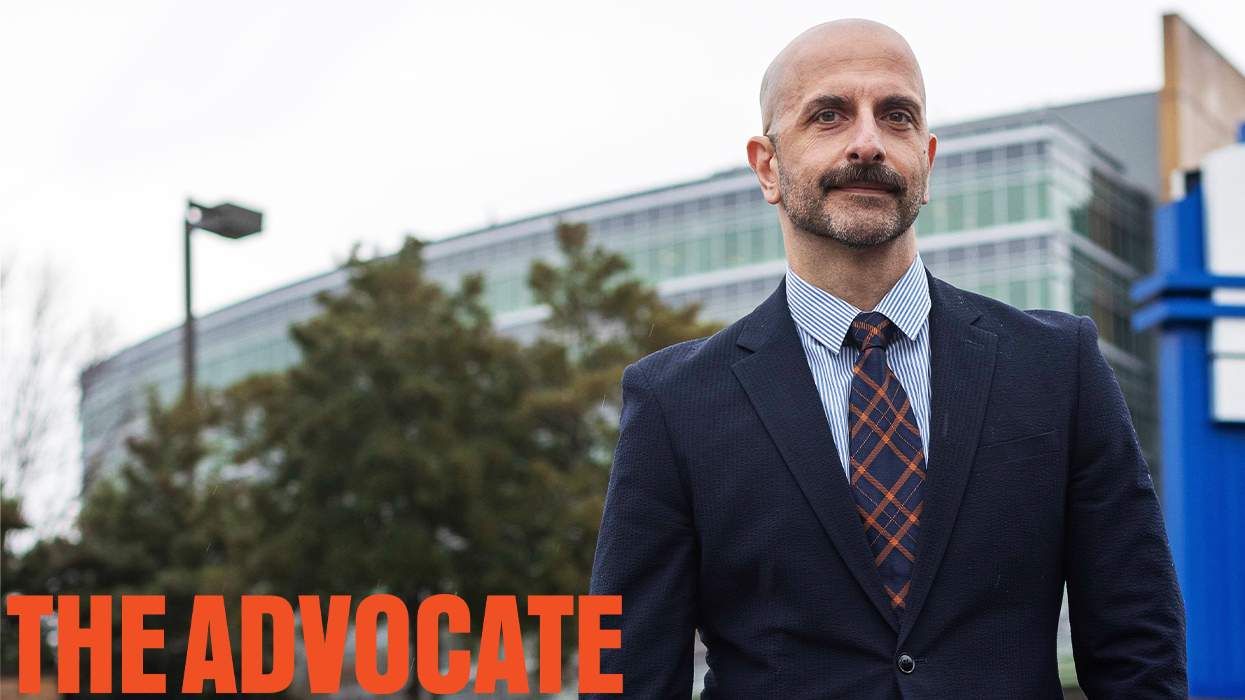

When Dr. Demetre Daskalakis stepped away from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in August, his resignation as director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases did not land quietly. It detonated.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

“I find that the views [Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.] and his staff have shared challenge my ability to continue in my current role at the agency and in the service of the health of the American people. Enough is enough,” he wrote in a resignation letter he shared publicly on social media.

He said he was leaving because the CDC, the once-premier public health agency tasked with protecting the health of people in the U.S., had been transformed into a political instrument, with its scientific mission subverted, vulnerable populations erased, and evidence distorted. The agency, he wrote, had submitted to “radical non-transparency” and “unskilled manipulation of data.”

What is happening at the CDC is part of the second Trump administration’s attack on science. The administration has cut billions of dollars from cancer research, vaccine research, and other breakthroughs the medical community had been working on for decades.

Now, on the outside, Daskalakis and others worry about those still inside. “I feel bad for my people who are inside the CDC,” Daskalakis says. “The CDC is now a weapon. That is why I left. The weaponization of public health is happening, and I am not crying wolf.”

Part of why his warnings resonate is the messenger himself. Daskalakis is a tattooed, out gay infectious disease physician who speaks plainly about queer sexual culture, goes clubbing, and wears harnesses at charity galas.

After Daskalakis’s resignation, U.S. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky called him “a guy that is so far out of the mainstream, I think most people in America would discount his opinion.”

But Daskalakis leans into the drama.

“I don’t care about the garbage,” he says. “You want to come for me? Come for me. You’re just making me more trusted in the community that I love.”

A 49-year-old Toy Doctor’s Kit

For more than two decades, Daskalakis has been a through line in America’s responses to HIV, mpox, measles, and other respiratory infections, including COVID-19. His mix of technical fluency, cultural competence, and moral clarity has made him one of queer public health’s most trusted messengers. Today, he is sounding the loudest warning of his career.

During a recent video interview with The Advocate, Daskalakis, 52, retrieved an object from off-camera: his Fisher-Price doctor’s kit from when he was 3 years old.

“It is 49 years old. It is in pristine condition, because this is why I wanted to be a doctor,” he says, holding up the plastic box containing a play stethoscope and other toy medical tools.

Daskalakis grew up in Northern Virginia without physician role models. He is the son of Greek immigrants, and his grandmother spoke only Greek. As a child, he would take imaginary temperatures of his grandmother’s friends, and if they refused, he would announce they could leave.

But it was an interest in HIV that inspired him. As a resident assistant in undergrad, Daskalakis organized an AIDS Memorial Quilt display to benefit New York charity God’s Love We Deliver. He carried a panel through San Francisco International Airport, overwhelmed by its weight and shape. On College Walk, Columbia’s main artery, he watched mourners collapse over names sewn into fabric.

“This is what I want to do,” he remembers thinking at the time. “Make sure that people don’t have to die from this disease anymore.”

His path from that moment forward reads like an index of the crises that shaped late 20th- and early 21st-century queer life. In medical school at New York University and later during his residency at Harvard’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Daskalakis cared for people living with advanced AIDS. As a resident at Fenway Health, he met his first transgender patients. At Harvard, he earned his master’s of public health degree.

After hearing a radio report about a case of multidrug-resistant HIV in New York City, he rushed back to the city, launching HIV testing programs in venues like Paddles, the city’s iconic leather and fetish club. There, he built trust where others feared to tread. In one now-legendary story, a leather-clad man handcuffed him to a leather pagoda mid-test.

“I can test you while I’m handcuffed,” he told the man calmly. “But when I’m done, you’re going to uncuff me.” He then continued the appointment one-handed.

Eventually, his work led him to the highest echelons of public health. As New York City’s deputy commissioner for disease control, he helped steer responses to HIV, meningitis, measles, and COVID-19. Later, at the CDC, he oversaw HIV prevention nationwide.

A Hostage Situation

The CDC’s collapse is not theoretical, Daskalakis says. It is operational, ideological, and moving quickly. “The scientists are amazing,” he says. “But the scientists are being held hostage in a system that will not allow them to do their job.”

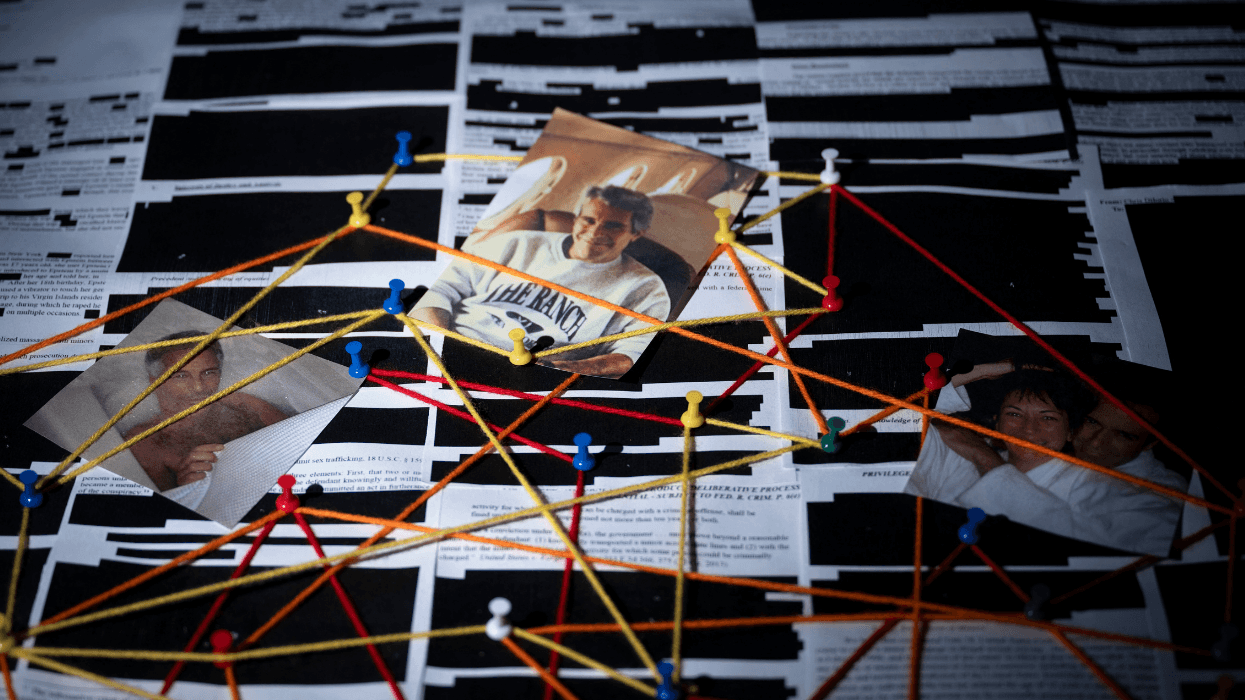

In November, the CDC abruptly altered its vaccines and autism web page to imply a possible link that has been discredited by every major scientific body. The change bypassed all normal review. No scientific experts were consulted, no internal process was followed, and the divisions responsible for vaccine science were not notified.

Dr. Debra Houry, the CDC’s former chief medical officer, who resigned alongside Daskalakis, says the episode captured the crisis precisely.

“None of the scientific leaders at three of the centers that would have been aware of that change had been consulted,” she says. The top of the agency, she adds, is now packed with political appointees. “Usually, there are two to three. I think there are 13 now, maybe more. The right part of the CDC is still there. It is that top layer where they are not engaging career staff.”

And the consequences are immediate. “If somebody goes to the CDC website and sees the information on vaccines and autism, they might question whether to get their child vaccinated,” Houry says. “We know that it is safe.”

Dr. Nikki Romanik, distinguished senior fellow in global health security at Brown University’s School of Public Health and former deputy director and chief of staff for the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy, says the collapse was visible from the inside long before the public saw it. “Public health only works if the science is intact,” she says. “When scientific review is sidelined, everything else falls apart.”

To Daskalakis, the pattern is unmistakable. Fringe theories and pseudoscientific briefings have begun replacing evidence. The “Tylenol moment” — when President Donald Trump and Secretary Kennedy told pregnant people to avoid acetaminophen because of unproven links to autism — was galling. The drug has been deemed safe during pregnancy when taken as directed.

“It is a concerted effort to get people to mistrust experts, science, doctors,” he says. In a landscape where the Food and Drug Administration is destabilized, the familiar refrain to “do your own research” becomes a vacuum in which misinformation takes hold.

Dr. Daniel Jernigan, former director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, calls the vaccine website shift a rupture. “It was completely inaccurate without any CDC staff providing any input,” he says. “It is astounding.”

The breaking point for Jernigan, Houry, and Daskalakis came when Kennedy fired newly confirmed CDC Director Dr. Susan Monarez, who had committed to protecting the scientific process. “That pushed us across it,” Jernigan says. “We resigned so we could speak out.”

The trio, who call themselves “D3,” describe an agency stripped of its core functions. Where the CDC once anchored the national public health system, it is now, Daskalakis says, “a place where they have demonstrated that they are untrustworthy.”

He adds that the public health infrastructure itself is breaking and points to the dismantling of the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response. “When we had bird flu, I had people I could talk to in the White House,” he says. “That is gone.”

Romanik, who ran that office under the Biden administration, agrees. “The office was gutted,” she says. “There was no one left to coordinate anything when the next emergency hits.”

An Erasure of LGBTQ+ Data

When mpox emerged in 2022, Daskalakis watched the early weeks of the outbreak with growing concern. “They didn’t know anything about health in the way you need to know to deal with something transmitted in the context of sexual activity in most people in the U.S.,” he recalls.

What crossed his mind was “I think they need some help,” he remembers.

Jernigan, whose expertise includes pox viruses, says Daskalakis was indispensable. “He was way out in front and doing the right thing. If we had not had him, I don’t know exactly how we would’ve done it,” he says.

But tracking and responding to future outbreaks in the queer community will be made more difficult by the administration’s efforts to erase data about transgender, nonbinary, and LGBTQ+ people from health guidance and data systems.

Romanik speaks bluntly about the human cost of that erasure. “How many times can you kick a specific population in the gut before they go underground and stop getting preventative care? It breaks my heart.”

What’s lost, she says, is not just scientific accuracy but the basic conditions for dignity.

“You should not try to erase any type of population ever,” she says. “And you shouldn’t ever try to make people feel that their health is not important.”

The Next Steps

Public health today requires what it has always required, Daskalakis says. Not only science but courage. Not only data but trust. Not only expertise but community.

“Open your ears and your eyes and listen,” Daskalakis says. “Don’t be an asshole.”

In 2026, Daskalakis is beginning a new chapter as chief medical officer at Callen-Lorde, the nation’s flagship LGBTQ+ community health system in New York City. Built after Stonewall and serving tens of thousands of patients annually, Callen-Lorde remains a national model for culturally competent LGBTQ+ health care.

For him, the move is a return to the community-anchored work that shaped him. The CDC may be unrecognizable. But Daskalakis is not. His voice — sharp, grounded, and unafraid — remains unmistakably ours.

“You have to follow your North Star,” he says. “But you are not the one who decides where the North Star goes.”

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.