Attacks on transgender rights didn’t start with Donald Trump — but neither did the movements resisting them.

Since 2022, 25 states have banned most gender-affirming care for trans youth, six of which make it a felony for doctors to provide the treatment. Two have banned surgery only. While only 14 and the District of Columbia have shield laws protecting the care, a small but growing coalition of “sanctuary cities” for trans people are filling in the gaps.

Many may know the term in reference to municipalities that limit cooperation with federal authorities like Immigration and Customs Enforcement that target immigrant communities, but “sanctuary cities” is also used to describe these places that aim to help transgender people.

These cities — of which there are an estimated fewer than 10 in the U.S. — are not superficial “safe spaces.” For trans kids and their families, they are meant to ensure that local resources aren’t used to aid officials from other jurisdictions prosecuting them or their doctors. They also prohibit officials from sharing information about someone’s gender, sex, or health care.

While the resolutions can’t overturn state or federal laws, “the closest point to the community is a council,” says Eric Guerra, mayor pro tem of Sacramento. The City Council voted unanimously to make Sacramento a sanctuary city in March 2024. It was the first state capital to adopt that status.

“It goes down to the fundamental belief that people are people, and we should respect people for who they are,” says Guerra, who was a council member at the time. “And that has helped let our cities move forward.”

Sanctuary city resolutions usually come when residents approach their city council members with evidence showing why they’re needed.

There wasn’t just one person who came forward and motivated officials to declare Olympia, Washington, a sanctuary city in January. Instead, several LGBTQ+ residents commented publicly that they were “feeling very fearful and unsafe” in the wake of Trump’s election, says Assistant City Manager Stacey Ray. The City Council initiated the resolution in response.

Public testimonials from community members about how they have been negatively impacted by anti-LGBTQ+ laws is what Guerra says can be legally considered “factual points of incidents that occur that go contrary to our nation’s fundamental beliefs.”

From there, resolutions go to city attorneys, who must make sure that they don’t go against the state or U.S. Constitution. Ray describes it as a “long, arduous process,” and says officials must consult with local law enforcement about “what we can do within our legal parameters” to enforce the resolution.

“One of the things our council said is they wanted something that was actionable. Not just ‘pretty words,’ but they really wanted something that would be seen as authentically providing the safety that folks were asking for,” Ray says.

California and Washington State have shield laws for abortion and gender-affirming care, making resolutions like those in Sacramento and Olympia in line with state law. Democratic-controlled cities passing local ordinances in Republican-controlled states can lead to more complications, like in Kansas City, Missouri.

The City Council there approved a sanctuary resolution for gender-affirming care in May 2023, shortly after the state legislature passed a bill banning the treatment for trans minors. While the city could not overturn state law, Mayor Quinton Lucas, who introduced the resolution, ordered local police and city personnel to make enforcement “their lowest priority.”

“It just means you have more fights, frankly,” Lucas says. “It also means that here in the red states, we have a little more experience with fighting.”

Sanctuary city resolutions are still helpful in blue states, especially under a federal government hostile to LGBTQ+ people. Since taking office in January, Trump has signed executive orders denying the existence of transgender people and banning federal support for gender-affirming care for those under 19.

“Trump has the authority over a bunch of federal employees, like with the civil rights protections he’s rolled back in hiring specifically for the federal government,” Guerra says. “I think people forget that those roles and those stages also exist in their local community.”

Trump has threatened to withhold federal funding from immigration sanctuary cities and could potentially do the same for cities that protect transgender health care and abortion access, prompting more than a dozen local governments — including the city of Sacramento — to file a lawsuit against the administration.

For Guerra, who is an immigrant, the benefits of protecting a marginalized group far outweigh the risk the Trump administration poses. Lucas also “encourage[s] every mayor with that opportunity to” stand up for LGBTQ+ rights.

“The thing that motivated me was our shared humanity,” he says. “When your state government or your federal government is saying you don’t deserve to exist and [is] trying to remove you as a human being, I think that those of us with whatever power, we have a duty to act.”

This article is part of The Advocate's Nov/Dec 2025 issue, on newsstands now. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Apple News, Zinio, Nook, or PressReader.

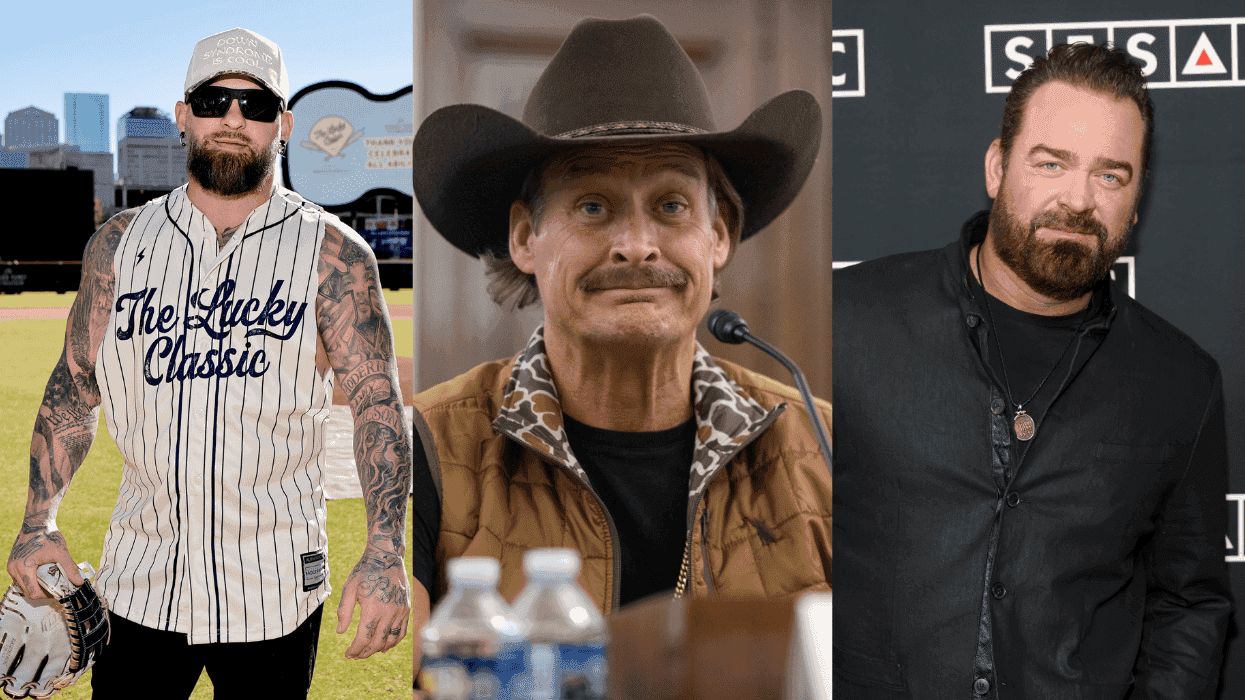

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.