Miss Major Griffin-Gracy is a singular force in our community.

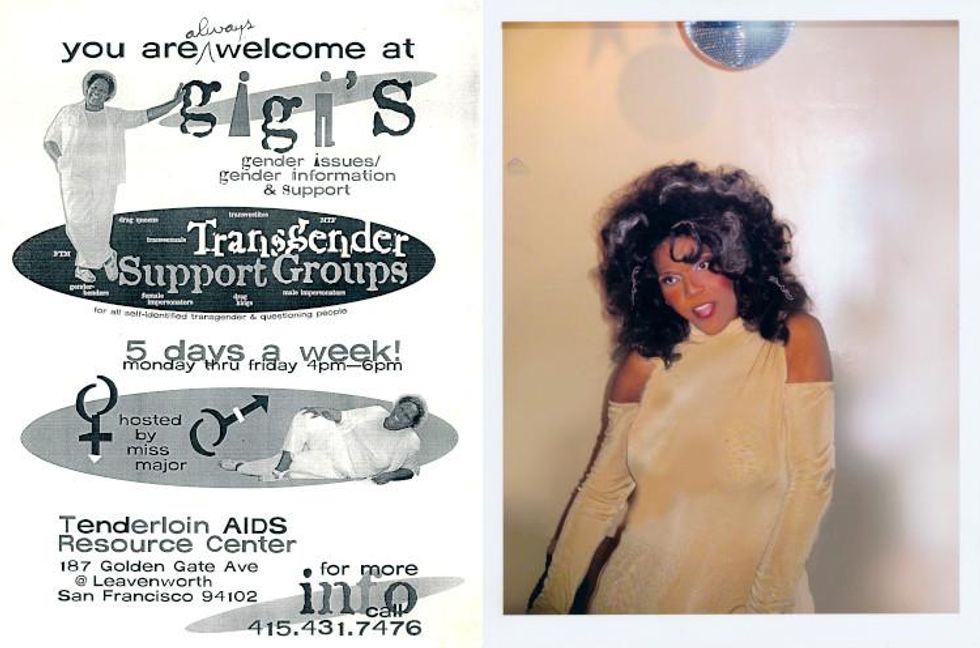

A veteran of the Stonewall uprising, Miss Major's dedicated the past 50 years towards working and advocating for incarcerated trans folks, particularly trans women of color who, like Miss Major was, are often housed in men's prisons. She's worked for multiple HIV/AIDS organizations, lead support groups around the U.S., and was the first executive director of the Transgender Gender-Variant and Intersex Justice Project, a role she held until she retired in 2015.

Now 80 years old, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy lives in Arkansas and is one of the executive producers of the new series, Trans in Trumpland (streaming on February 25th on Topic.com and the Topic channel through AppleTV, Roku, and Amazon Prime). On this week's episode of the LGBTQ&A podcast, Miss Major speaks about how different the trans experience is today, achieving "icon" status, and why she wants to be an example for other trans women. "There aren't that many Black girls still alive. Let them know that they can get here too."

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Jeffrey Masters: You had a stroke about a year and a half ago. How are you doing now?

Miss Major: I'm doing really well. I have to speak a little bit slower now. I have a problem getting around, but basically I'm doing okay. So, thank God for medicine. I'm doing fine.

JM: You were 22 when you moved to New York City. How did you find a trans community back then?

MM: Are you kidding? Trans community was everywhere. I went immediately to 42nd street. Everybody went to 42nd street: trans girls, everybody. Finding them was not a problem. They were everywhere. From there, I found an apartment that I moved into. It was six floors of nothing but trans girls. It was fabulous. There were so many of us that it was a full life.

JM: You were friends with Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Crystal LaBeija. You worked with Storme DeLarverie. What's it like to see that these people now be considered icons?

MM: They're just friends to me. They're not icons. I don't know where that term came from, how we got stamped with it, but they're just friends. Even though it's happening and it's happened to me, you really don't pay attention to when it started. All the sudden it's, "Oh my God. There's Major." And it's like, "Who? What? Where? Oh me." I guess, 20 years ago it started happening. But I didn't notice the change coming, didn't see it coming.

JM: Unlike those women, you have lived long enough to be celebrated in your lifetime. Do you feel like your work is acknowledged?

MM: I do in a sense that the community I'm from acknowledges me. The gay community doesn't, and that's where the hurt is, but you get used to that: the fact that they remember Sylvia and Marsha loudly. And the people who were incidental in stuff, they don't remember, but that's fine. You just go on and do what you have to do. Keep going forward.

JM: Before Stonewall in the '60s, were you involved in activism?

MM: I was involved with it when my friend died, Puppy. She was murdered in her apartment and we knew at the time that someone who knew her had murdered her. And the police did not care. It didn't matter to them at all. And so that started my activism, because then I wanted to know what cars people would get in. What the person looked like that they got in with. When they left and when they came back was important. And all of us started keeping notes, to keep up with the johns because we didn't know what would happen to us then.

JM: To keep yourself safe, while doing sex work, were you learning everything by trial and error?

MM: It's done by trial and error, and you paid attention to what the girls show you, because you don't know it all. Nobody does.

JM: You've said that you loved doing it. You loved being a sex worker. What did you like about it?

MM: The number of guys. I went into this because it was fun. Other girls went to it for survival and I was lucky that I've always worked. I got a job in social work, so I had the job to take care of my day expenses and extra money from the johns.

JM: In the apartment building that you lived in with six floors of trans women, what percentage were also doing sex work?

MM: All of them. One or two might not have been doing that, but all of us were. The entire building except for maybe two people had to do that. It was hard. But I guess being around people who thought like you did made it seem possible. It made it worthwhile.

JM: With Stonewall, now 50 years later, what stands out the most in your memory from that night?

MM: What stands out to me is that I got knocked out early because I heard from the girls that you need to piss the police off so that they would knock you out. And so I was concerned about getting hurt, getting something broken, or being bashed where I couldn't work anymore. So I spit in some guy's face and he knocked me out. Other than that I don't remember nothing.

It was the decision. Because it was safer. I was young and I was pretty, and I wanted to keep my face.

JM: There were laws against cross dressing at that time. Were you presenting as a woman that night?

MM: Oh yes. Always. See, child, I loved the, "You're beautiful."

But you had to have three articles of men's clothing on so that they'd know you were a man. So I wore a t-shirt under my blouse. I had earrings at the time that said, "I'm a man." And a pair of underwear. That's what it was.

JM: Much has changed since then, much still needs to change. On an individual level, how has your life changed in terms of being trans?

MM: Well, my life is better. I mean, in general. I can shop, I can go about my day in whatever attire I please. That has changed a lot. What hasn't changed is one or two people have an attitude about me. But with the way things have turned out, I don't care. If they don't like me, oh well. And I go on about my business.

JM: When you were incarcerated in a men's prison, was there ever discussion about housing you with the women?

MM: No. There was never any. I went straight to the men's and that was fine because when I got there I let them know I'm a woman. And then I got locked up. But sometimes in Sing Sing [Correctional Facility], I was in the population and it was fine. No one wanted to beat me up. Of course I was 6' 2" and 250 pounds. So don't you fuck with me. Basically it was nice.

JM: What was nice specifically?

MM: Well, in Sing Sing, it was like being in New York City on 42nd Street. You had some freedom to move around. There were the couple of girls in prison with me. They were in every prison I went to. So it was good because the bad stuff was going to happen eventually.

JM: You credit that time as where you learned about prison abolition, particularly how it affects the trans community.

MM: It was in Dannemora, especially. There was a prison and a mental institution and they put me in the mental institution first. That was hard because they stripped me down in front of everybody and made me walk to places naked. So I became aware of what was going on. And then they had the Attica prison riots and brought some of those guys and put them in the same cell block I was in, in the hole.

And I got to talk to them and learn what the differences were and that everybody suffered in there. I learned not take it on as if I was the only one that it had happened too. It happened to all of us. I then realized what I had to do. I had to do something to keep the girls safe in there.

JM: Now you're an executive producer on the docuseries, Trans in Trumpland. Why did you want to be a part of that?

MM: Because people need to know that it's not just Trump...this country is what's fucked up. Not just him. He got in because of that. Something's wrong with that.

JM: I think it's a good message that the series shows that trans people can exist and live outside of major metropolitan cities.

MM: Yeah, and that's changed. I'm in Arkansas now. I never thought about coming to Arkansas because you figure I'm Black, I'm male, I'm female. And Arkansas? No, never.

But now I can move here and it's been nice here, quiet and unobtrusive. I go about my day and they don't bother me as much as they would have in a large city. So it's amazing the change that's happened for sure.

JM: The change in the world or the change in your life?

MM: The world in general. Because I was traveling before this pandemic hit and everywhere I went, I was accepted. I didn't have to hide as we did in the 60s and 70s. It's changed and it can get better.

JM: How has your experience of your own gender evolved over your life?

MM: Well, it's an everyday thing. You become confident in more stuff every day. You become more secure in your standing. It's who you are. And it has an effect on you when things change outside your purview. You do feel like you belong, not just alone in the dark. Sometimes the light is on us and that's a good thing.

I am who I am and I feel feminine, and the masculine things don't affect me.

JM: Many in the community call you mom and mother. Was it always important to you to be a mother?

MM: No. In the beginning, I never thought I would be. But as time has evolved, more and more people ask me. That's a very sweet thing that they've done. When they ask me to be their mother, it means something to me. What do I say? No? It make me feel good that they trust me enough to do that. And I try to make sure that I don't let them down. That's important.

JM: How many people call you mother?

MM: 99 call me mother...It's a large number. I take it very seriously. It's important to acknowledge it, to respond and to be there when they need you. And the best way to do that is to call and see what's happening, to find out how they're doing and what's happening in their lives. Not just mine.

JM: While you have mothered many, your own parents struggled with your gender. Is it too simple to draw a line from what was missing from your own parents to what you do now for other people?

MM: My parents had to go through whatever they did, and the position that they took on me was their position. There's nothing I can do about that, but I can do that when someone comes to me. Parents, when they're given a male or female at birth, they expect that person to grow up and stay that thing. And they're entitled to that. If they can learn from it and gradually change with you, good. If they can't, also good, because you can't force this on them.

JM: Did your parents ever come around?

MM: Oh, my mother died waiting for me to change. My father lived about 10 years after mother died. He came around. He wouldn't call me she, but he acknowledged that Miss Major did exist. So what more could I ask?

JM: Do you have any friends that are trans and your age?

MM: I have girls that are close and getting to the point, but that's few and far between. Not that many. I don't know any that I can recall at all. Of the girls who were in that building, there may be one still alive.

I do good to be here. Most girls don't make it past 30. It's a rough life that we have...so it's important that one or two of us make it. It's hard. It's very hard when you think about it.

JM: Does that affect how you think about death?

MM: I don't think about it. Once in a while I do. When my son was born, the older one and now this new one, I thought about it some. I would want to be here for his getting older, and to get to know him like I have my other son. But I don't think about it because we all have to get there sometime. And I figured, well, why worry about it? It comes when it does.

JM: What big things do you still want to do?

MM: Now? God. I want to start traveling again. I want him to go places and get to know the girls that are out there. I hear about stuff on this Zoom thing, but I don't get to touch them with my hands. That's what I miss a lot. Being there for them. Let them see and touch me. I'm alive. There aren't that many Black girls still alive. Let them know that they can get here too.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Trans in Trumpland premieres on February 25th on Topic.com and Topic channels through AppleTV, Roku, and Amazon Prime Video channels.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Alok Vaid-Menon, Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Tracey "Africa" Norman, and Roxane Gay. Episodes come out every Tuesday.