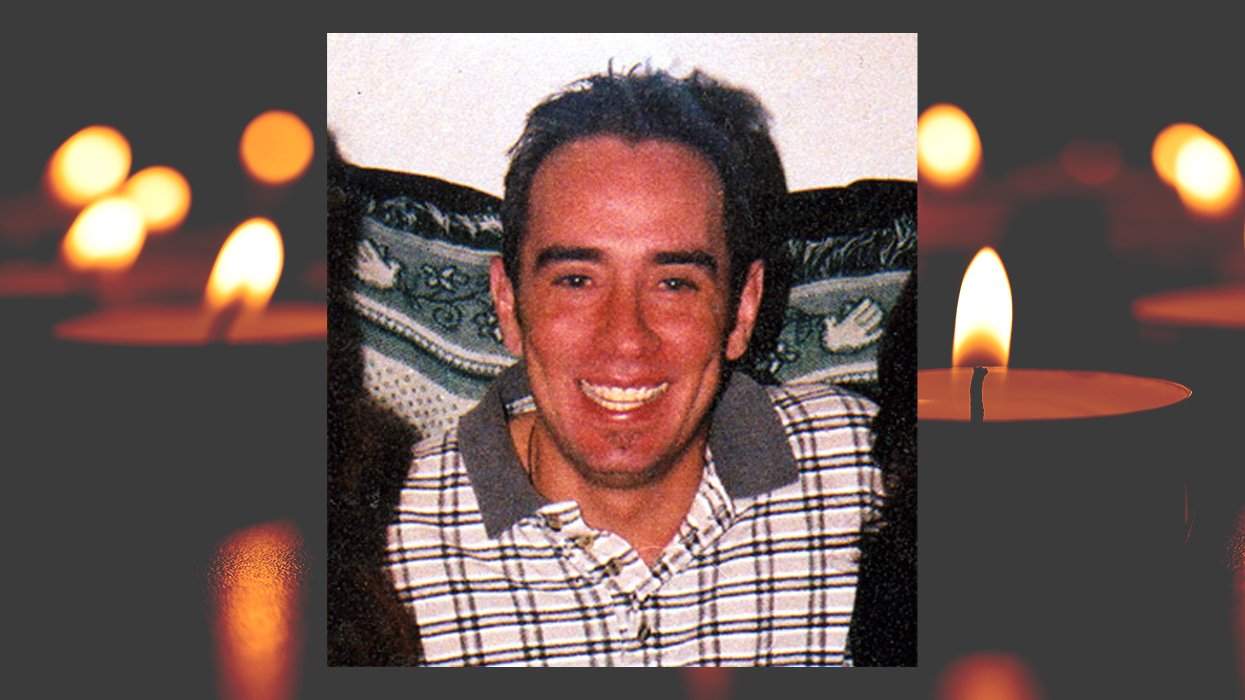

For more than two decades, Debbie and Jacquelyn Espinoza have gone to bed each night wondering what became of their little brother, Ricky Espinoza, after he disappeared in June 2001.

DNA evidence that was stored for years without review could hold the key to understanding Ricky’s fate, but an unexpected hangup at the Colorado Bureau of Investigation could leave Ricky’s case — and thousands of others — in bureaucratic limbo for years to come.

Originally the Espinoza family was told there was no evidence collected from Ricky’s body, as it was too decomposed. But several specimens were taken and will be retested by the CBI in an attempt to answer a 23-year-old question.

“Whoever this monster was that killed my brother, then threw him in the trash bin, they need to be really punished for taking a life and abusing a corpse, and for doing that to my sister and I for 23 years, putting us through hell,” Debbie Espinoza said.

What happened to Ricky?

Ricky Arthur Espinoza’s case is an unfortunate morass of brutality and intrigue. He was last seen alive by his family on June 23, 2001, five days before his killing. He was born on Oct. 19, 1963 and was a 37-year-old Colorado Springs resident, having moved back home after living in Denver for several years. Ricky had recently graduated from cosmetology school. “My brother was blessed with his good looks and was a sharp dresser and fashionable with his hair, a great cosmetologist,” his sister Jacquelyn Espinoza told The Advocate.

Ricky briefly lived in California, residing in North Hollywood and working as a courier for a law office as he was considering a career change, his sisters said. “He would have been a good attorney, because he wouldn't back down,” Ricky’s sister Debbie added.

“Ricky was at a pivotal point in his life, and he wanted to further his education. He had been talking about going back to college [and] he was contemplating what he wanted to do. … Then they ended his life,” Debbie said.

On the Saturday Ricky was last seen, he went to a wedding reception with his family. Around midnight, he told his mother (with whom he was very close, his sisters say) that he was going to Eros Arcade, an adult bookstore known to be frequented by the area’s gay men. He set off on foot, which was unusual as he was known to bike around the area. The bicycle Ricky would have taken remained chained outside his mother’s home for years after his disappearance.

Ricky’s last contact with his family was around 4:30 on the morning of June 24, when he phoned home to tell his mother he was staying overnight at J’s Motor Hotel, which was located at 820 N. Nevada Ave. in Colorado Springs. The motel no longer stands, and it appears based on online reviews that its last booking was sometime in 2008 and the lot it once occupied is now part of the Colorado College campus. It was about a seven-minute drive from the former home of Ricky’s mother, who lived in southwest Colorado Springs on East Las Vegas Street.

For five days after Ricky’s last phone call, his family stewed in dread, desperately trying to figure out his fate. Ricky’s nude body was ultimately found June 28 by a worker at the Fountain Landfill at 10000 Squirrel Creek Rd., about a 25-minute drive southeast of J’s Motor Hotel.

An undetermined cause of death

The body found at the landfill had been mangled by a bulldozer and was so decomposed that Ricky was identified by fingerprints and dental records. Ricky’s “perfect teeth” were an identifying factor, Debbie Espinoza told The Advocate.

Because Ricky’s body was severely traumatized postmortem, it became difficult to conclusively determine the cause of death or even which injuries were sustained before or after his killing.

An autopsy report provided by the El Paso County Coroner’s Office and reviewed by former medical examiner Dr. Deborah Johnson ruled his death a homicide with undetermined cause.

At the time, officers and investigators told the Espinoza family that they were unable to take DNA samples. “That was a lie,” Jacquelyn said. “They took DNA, they took a rape kit.”

After pressure from activist Rob Wells and the family to retest the DNA from the scene, the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office agreed to a peer review by the CBI to “retest items from the investigation,” a letter sent to the family and viewed by The Advocate read.

Ricky’s blood alcohol limit was .296, over double the state’s legal limit for driving, but that could have been caused by fermentation during decomposition, said Johnson, who examined Ricky’s body and is currently a forensic pathologist at Pikes Peak Forensics, having left the El Paso County office in 2002. There were no signs he was killed by toxicity.

“Under the methods we have today, they can probably still get good DNA” on a severely decomposed body, Johnson noted. But, she added, “Those methods were not available then. Usually it’s your best bet to save a piece of bone because that seems to be less affected. But back 20 years ago … our thought was, we’ll save [specimens] if we can, because there may be new techniques.”

It is unlikely that Ricky’s body was found at the scene of the actual crime, meaning he could have been killed anywhere, said forensic analyst T.J. Payne. “Right now, we only have a dump site and no actual crime scene which just adds another level of complexity to this case,” Payne told The Advocate. But Payne theorized that “this was done by someone who ran on impulsive behavior and managed the crime scene after the incident took place.”

There were inconsistencies in the way Ricky’s death was reported in the Colorado Springs newspaper The Gazette versus the autopsy report, Payne noted. “Postmortem injuries immediately made me think this was a disorganized sensational murder,” when in fact most injuries to Ricky’s corpse likely were sustained because of how his body was disposed of, Payne said.

Original reporting on Ricky’s death by the local papers reflected the mindset of police at the time when it came to LGBTQ+ victims of murder.

El Paso County Sheriff's Detective Gabe Firpo told the Colorado Springs Independent in July 2001 that Eros Arcade, which still stands at 227 Bonfoy Ave. in Colorado Springs, now as the Ambassador Adult Theater & Arcade, was a “well-known pick-up place” for gay men. The theater is about a five-minute drive or 50-minute walk from J’s Motor Hotel, where we know for certain Ricky was last heard from.

But it’s unclear if Ricky was last seen at Eros Arcade. El Paso County Sheriff’s officers told the Independent in July 2001 that they were trying to ascertain if Ricky checked into J’s Motor Hotel with someone he met at Eros Arcade, but it’s unclear what they determined — Ricky’s family was never informed of any leads.

Requests by The Advocate to view the 23-year old police reports were denied. The El Paso County Sheriff’s Office said via email it does not disclose records for open, active investigations.

The family claims that Ricky’s case was taken less seriously because of his sexuality, and press articles from the time were less than sympathetic.

“During the time when Ricky was killed, the narrative in the press that they wrote about Ricky in the newspapers was, to me, falsely and recklessly written to demoralize him,” Jacquelyn said. “It really tore me apart. They completely obliterated his character, and they associated it with people that were doing illegal activity. I believe Ricky was marginalized to the public, and they wanted to set up his life as insignificant.”

A crisis in Colorado

Unfortunately for the Espinoza family, the system that should provide answers about Ricky’s death is functioning less than optimally.

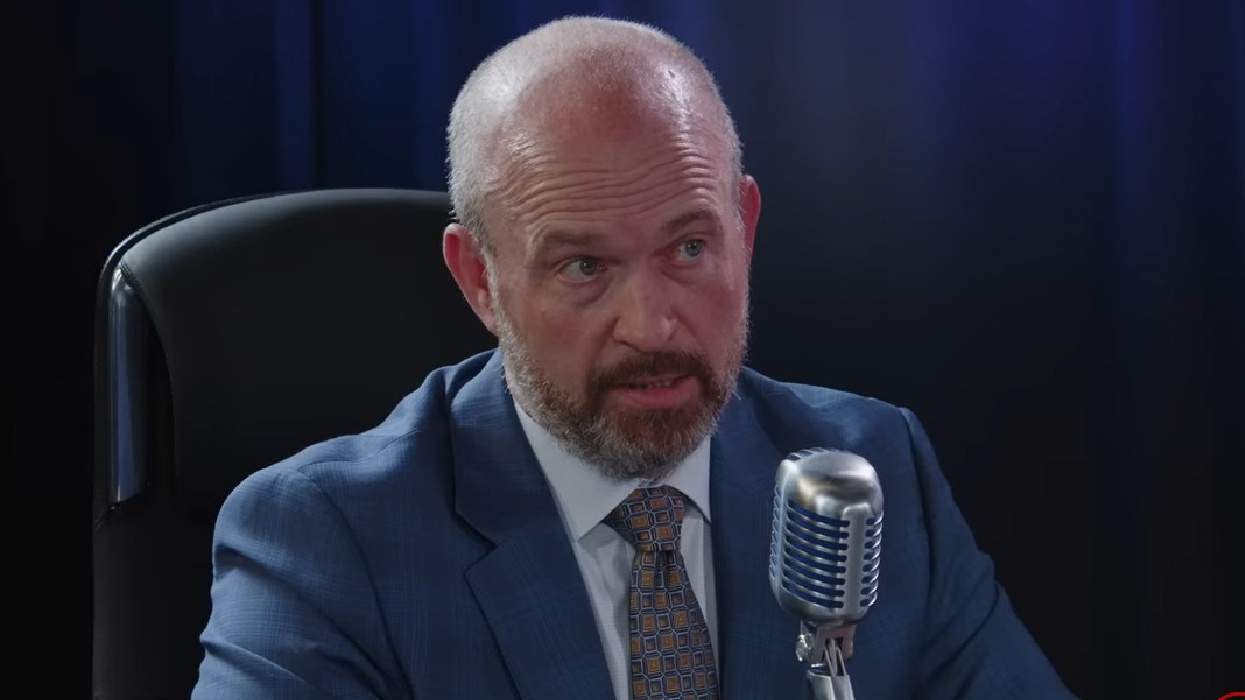

Colorado has a backlog of 1,750 unsolved murder cases dating as far back as 1970, said Rob Wells, a former U.S. Coast Guard special agent and criminal justice professor turned victim advocate who founded the advocacy group Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons to draw attention to unsolved crimes in Colorado and hopefully solve a few.

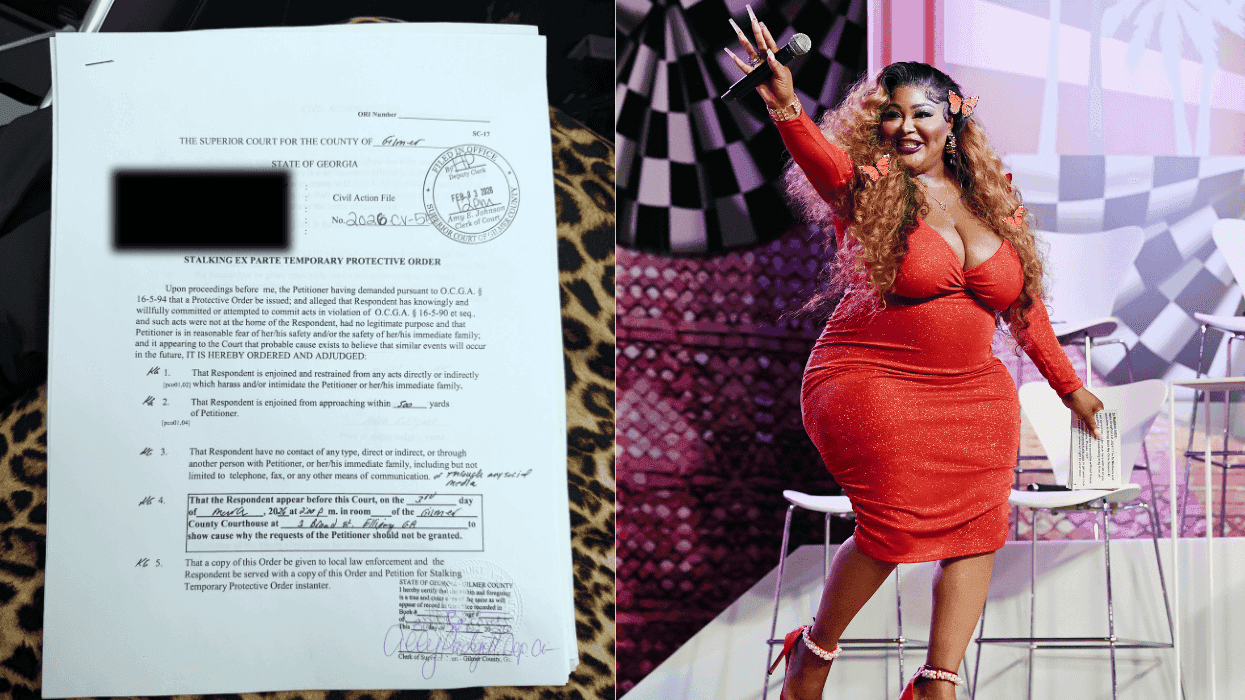

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which handles the forensic analysis for police departments across the state, recently found that former forensic scientist Yvonne “Missy” Woods had either manipulated or omitted data in supposedly hundreds of cases dating back to the beginning of her career with the agency in 1994. This marked bad news for Ricky’s case and thousands of others. In Colorado, a case is considered cold if it has remained unsolved for three years or more.

“This discovery puts all of her work in question,” the agency said in a statement to CNN last March, adding that it would review all of Woods’s cases for data manipulation. The mishandling of DNA by Woods impacts the Espinoza case because it forces his family farther down the queue. Cases Woods analyzed now take priority as the CBI is forced to reexamine them and reckon with any possible malfeasance.

Woods not only presided over hundreds of cases during her career but also trained “generations” of scientists, her attorney told CNN. Anomalies in her work were first reported in September 2023, and she was placed on administrative leave the following month before retiring in November before the investigation concluded, the CBI’s internal audit published June 5 found.

“What this has done is delay the processing of DNA that they have,” Wells said of the CBI. “So we’re going to have to be patient… Kirby assures me it is going to get taken care of as soon as humanly possible, it is on their radar,” Wells said, referring to CBI Assistant Director Kirby Lewis.

For Ricky’s surviving family, the issue with the CBI compounds an already existing dread. “I’m anxious,” his elder sister Debbie Espinoza said. “I’m praying. … There’s no such thing as a secret. This isn’t going away.”

“We’re not going to let it go, and it will not be forgotten, I assure you that,” Wells added.