The courtroom was already tense on Tuesday morning when the first words of the day landed in Richmond, Virginia.

“Neither federal statutes nor the Constitution compel states to fund sex reassignment surgeries,” a conservative attorney told three judges.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

With that opening line, West Virginia’s solicitor, Caleb B. David, urged a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit to reverse its own ruling and reinstate the state’s categorical Medicaid ban on gender-affirming surgery for transgender adults. The case, Anderson v. Crouch, had returned to the court after the U.S. Supreme Court vacated its ruling and remanded it for reconsideration following the high court’s 2025 decision in U.S. v. Skrmetti, a case focused narrowly on restrictions for minors.

What unfolded over the next three-quarters of an hour revealed a court wrestling with medicine and money, yet constrained by its own limits of power.

David argued that West Virginia’s exclusion is not about sex or transgender identity at all, but “medical use.” Under that notion, he said, heightened constitutional scrutiny never applies.

“[Gender-affirming] surgery isn’t covered for any Medicaid beneficiary regardless of sex or transgender status,” he told the judges, using an outdated term referring to trans people. “The only relevant question … is what is the procedure’s medical use?”

Judge Paul Niemeyer tested that logic, pressing David on whether Medicaid’s requirement that states adopt “reasonable standards” had any meaningful teeth. David replied that states must retain broad discretion to allocate limited public funds, invoking concerns about safety, efficacy, and cost. Legislatures, not courts, he insisted, are entrusted with those judgments.

Judge Julius Richardson asked whether Medicaid recipients can still sue at all.

Related: W.Va. ends exemption from gender-affirming care ban for trans youth at risk of suicide

The judges’ questions centered on the Supreme Court’s June decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, which held that the Medicaid Act’s “any qualified provider” provision does not clearly grant patients a private right to sue under federal civil rights law. The ruling significantly narrowed the circumstances under which Medicaid beneficiaries can bring legal challenges against state health policies.

In light of that decision, Richardson suggested that the private right of action long assumed in Medicaid litigation may no longer exist. David agreed. Post-Medina, he said, “There is no cause of action.” If correct, that threshold issue alone could dispose of the case, no matter how unconstitutional the policy might be.

The case traces back to a 2022 ruling that once appeared to settle the question. That August, U.S. District Judge Robert C. Chambers ordered West Virginia’s Medicaid program to begin covering gender-affirming surgery for transgender patients, finding that the state’s exclusion “invidiously discriminates on the basis of sex and transgender status.” The lawsuit, brought by Lambda Legal, the Employment Law Center, and Nichols Kaster on behalf of Christopher Fain and Shauntae Anderson, challenged both Medicaid and the state employee health plan. A prior settlement lifted the ban for state workers; Chambers’s ruling extended that protection to all transgender Medicaid recipients statewide.

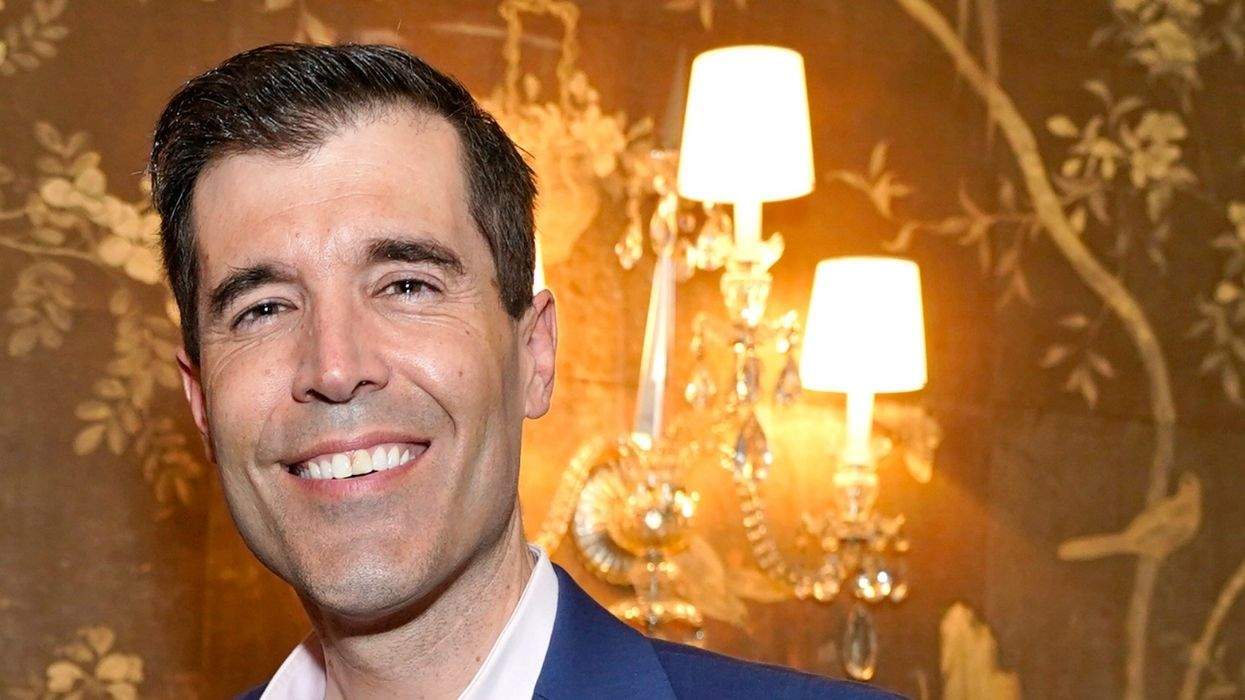

Next, Omar Gonzalez-Pagan, senior counsel and health care strategist at Lambda Legal, argued that West Virginia’s policy is not a neutral budgetary decision but a targeted exclusion that singles out transgender people through the language it uses and the population it harms. Unlike other exclusions in the state’s Medicaid plan, he said, this one does not merely describe a procedure — it describes who receives it.

Related: Supreme Court rules states can ban gender-affirming care for youth in U.S. v. Skrmetti

“This exclusion stands out because it doesn’t describe any particular service, but rather a broad category of services because of who attains them,” he told the court.

Niemeyer pushed back. The policy, he noted, excludes numerous surgeries while still paying for hormones, counseling, psychiatric care, and lab work for people with gender dysphoria. “It’s hard to say that they’re discriminating when they actually provide care for dysphoria,” he said. “They just don’t provide surgery.”

Gonzalez-Pagan countered that the effect of the exclusion is unlike any of the others the court had named. This one, he said, falls “exclusively” on transgender people — not overwhelmingly, but entirely. And he rejected the state’s claims about cost and medical uncertainty, pointing to unrebutted testimony that West Virginia never seriously studied the actual expense and that providing surgery could reduce long-term spending on mental health care and related services.

On Tuesday, again and again, Richardson returned to the Supreme Court’s requirement that plaintiffs show discriminatory intent, not merely discriminatory impact. Did Gonzalez-Pagan have evidence that lawmakers adopted the exclusion for that purpose?

Direct proof, he conceded, is absent from the record. Instead, he urged the court to look to circumstantial markers: the language of the exclusion, its exclusive effect, and what he characterized as implausible state justifications.

Related: Justice Sonia Sotomayor slams gender-affirming care ruling as 'state-sanctioned discrimination'

But even as the judges probed the past, the future loomed larger.

How far does Skrmetti reach? David insisted the Supreme Court’s reasoning applies broadly to medical regulation tied to sex. Gonzalez-Pagan argued just as forcefully that Skrmetti was about minors, and minors alone, and does not disturb the settled rights of adults.

In rebuttal, David acknowledged that West Virginia’s policy uses what he called “outmoded language.” In 2003, he said, gender dysphoria was not yet a DSM-5 diagnosis. But, he argued, changing the terminology would not change the law’s function. “If we said gender-affirming surgery … it wouldn’t change it,” he said. “The function of it is the exact same.”

When the arguments ended, Niemeyer thanked both lawyers for their “very fine arguments.” Then the panel left the bench.

No timeline was given for a decision. But what the judges decide now could determine not only the fate of transgender adults in West Virginia, but the legal framework governing Medicaid coverage for gender-affirming care across the entire Fourth Circuit and ultimately the nation as a whole.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.