This story is part of History is Queer, an Advocate series examining key LGBTQ+ moments, events, and people in history and their ongoing impact. Is there a piece of LGBTQ+ history we should write about? Email us at history@advocate.com.

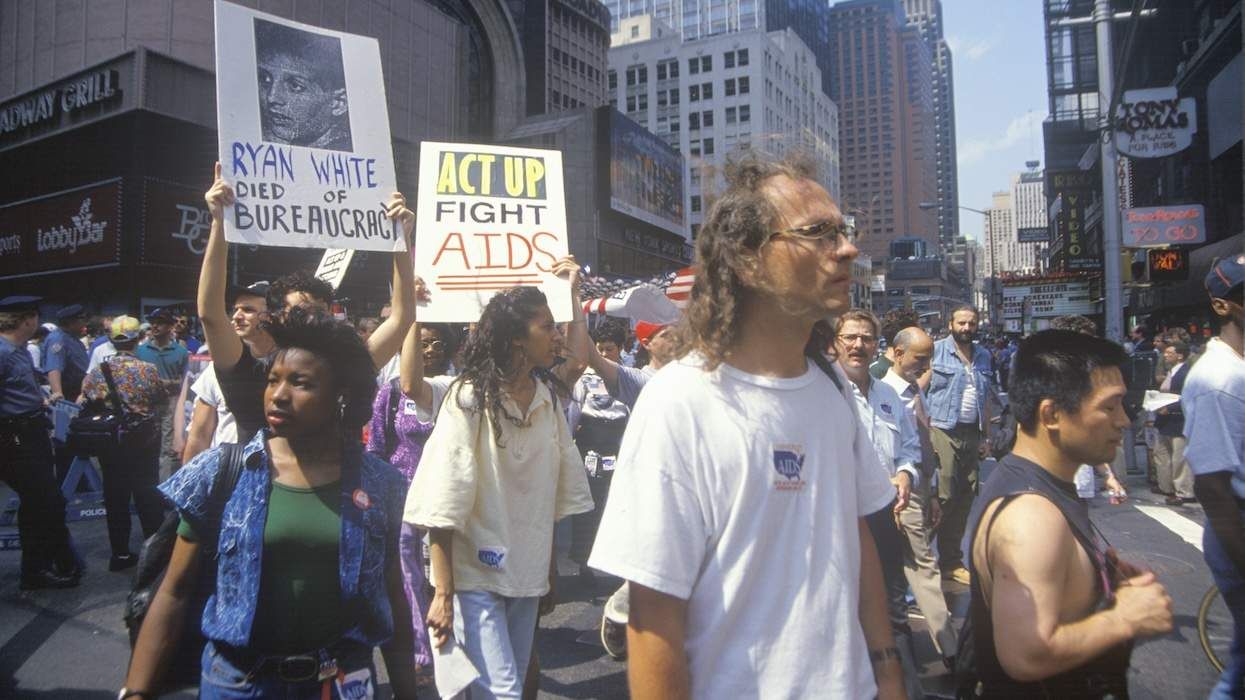

One of the most prominent and effective groups fighting for people with HIV or AIDS in the 20th century was the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP. Its confrontational tactics weren’t for everyone — some activists preferred to work within the system. But ACT UP made much progress, and some chapters are still active.

Here’s a brief history of the group.

The beginnings

The first ACT UP chapter was founded in New York City in 1987. Playwright Larry Kramer had called for the formation of a direct action group to deal with the epidemic, but many others were involved. About 300 people showed up for the first meeting, according to the ACT UP NY website. Between 500 and 700 attended meetings weekly, notes Sarah Schulman, who was involved with the New York chapter from 1988 to 1992 and interviewed many of her fellow activists for her 2021 book of ACT UP history, Let the Record Show.

For its logo, the group adopted the pink triangle — which LGBTQ+ people, particularly gay men, had been forced to wear in Nazi Germany — and the words "Silence = Death."

ACT UP soon protested on Wall Street against the high prices of AIDS drugs. The first one, AZT, had been approved in March 1987. Protests continued for several years; a 1989 one stopped trading at the New York Stock Exchange for the first time in history.

Chapters quickly started in other major cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boston, and San Francisco. Ultimately, there were more than 100 ACT UP affiliates around the world.

Actions and accomplishments

In 1988, members of ACT UP demonstrated at the Food and Drug Administration headquarters in Washington, D.C., to protest the slow approval process for AIDS-fighting drugs. Within a year, the FDA sped up the process. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, was responsive to activists’ concerns despite having once been called an “incompetent idiot” by Kramer. The two men came to respect each other, and Fauci oversaw much of the research that led to better drugs.

One of ACT UP’s most controversial actions was 1989’s “Stop the Church” protest at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. Cardinal John O’Connor, the Catholic archbishop of New York, had denounced the use of condoms to stop the spread of HIV, along with opposing needle exchange programs, sex education, and abortion rights. More than 5,000 people participated, with a rally outside the cathedral and a die-in inside, with protesters lying down in the aisles and chanting “stop killing us.”

ACT UP/Chicago grew out of another group formed in 1987. Its actions persuaded Chicago to triple its funding for the fight against AIDS and Illinois to double its. Another action brought 1,500 activists from around the nation to protest at public and private hospitals in Chicago, also calling for universal health care and condemning discrimination by insurance companies. “A key demand was that Cook County Hospital open its AIDS ward to women. The ward began admitting women the very next day,” notes the website for the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, into which ACT UP/Chicago was inducted in 2000.

Related: The Heroes of ACT UP Are Dying

In Los Angeles, ACT UP/LA demonstrated locally at federal and state buildings, city and county offices, and film and TV studios, and members traveled for protests at the NIH, FDA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more. One of its major accomplishments was convincing the L.A. County Board of Supervisors to establish the first AIDS ward in County/USC Medical Center (now Los Angeles General Medical Center), a move the board approved in 1988. ACT UP/LA won the first compassionate release for a woman with AIDS imprisoned in the U.S. and started the region’s first clean needle program. It worked with other chapters around the nation to have the definition of AIDS expanded to include women.

In September 1991, a newly formed ACT UP affinity group called Treatment Action Guerrillas (which soon split off as Treatment Action Group) staged an audacious act of protest, unfurling a giant condom over the home of homophobic U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms in Arlington, Virginia. It was printed with the words “Helms is deadlier than a virus.” Helms was the architect of a law that barred HIV-positive foreigners from coming into the U.S., which stood for decades until it was repealed by President Barack Obama in 2010. The senator also fought any funding for AIDS treatment, research, or prevention, and he attributed the disease to gay men’s “deliberate, disgusting, revolting conduct.” The protesters made sure he wasn’t in the house at the time: “The last thing we wanted was to spend our lives in jail for giving a senator a heart attack,” Peter Staley wrote in Poz in 2008, the year Helms died. The action received widespread media coverage, and Helms still complained about “radical homosexuals,” but “he never proposed or passed another life-threatening AIDS amendment,” Staley wrote.

Related: Peter Staley Talks The 'Heavy Dose' of Sex, Love, and Humor in ACT UP

- YouTube youtu.be

ACT UP/Boston, most active from 1988 to 1994, won expanded access to an experimental drug and better insurance coverage. In 1989, ACT UP demonstrators in San Francisco shut down the Golden Gate Bridge to call attention to the epidemic. In 1991, ACT UP’s Atlanta affiliate held a die-in at Grady Hospital to protest the six-month wait for people with AIDS to be admitted.

ACT UP chapters also advocated, with much success, for better portrayals of people with AIDS in the media, while busting myths around the disease, such as the idea that HIV could be transmitted by casual contact.

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, ACT UP members continued to protest at government offices calling for more action against AIDS and condemning inaction by presidents including George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

Memories

“Our first action was against the [Chicago Transit Authority],” ACT UP/Chicago activist Bill McMillan recalled to Chicago Magazine in 2020. “They had these terrible AIDS-phobic ads up, and they wouldn’t meet with us, so we decided to demonstrate. We were young and fresh, wearing new T-shirts because we had a new logo for ACT UP Chicago, which Danny [Sotomayor, a prominent local activist and artist] designed. We were overwhelmed by how many people showed up. At Clark and Diversey, we shut down the intersection. We had a die-in. That was my first arrest.”

“I’d never been an aggressive person before I joined ACT UP,” San Franciscan Virg Parks told SFGate in 1997. “But I liked the idea of a nonviolent organization that still said we’re going to be strong and powerful and angry and let them know that we are pissed off.”

Ann Northrop recalled the “Stop the Church” protest on a 2020 Advocate podcast. “Michael Petrelis got up on a pew and started screaming at the cardinal, ‘You’re a murderer, you’re a murderer.’ And the entire place erupted in screaming and yelling and people throwing things at us … I thought I was going to die.” But she lived on and remains an activist.

Related: After the 2024 election, we can be inspired by these historical LGBTQ+ movements against oppression

Matthew Ebert, writing in The Advocate in 2015, said ACT UP saved his life. When he walked into a meeting in New York in 1987, “I took to the room, and the energy and the passion of activism, and the beauty of men and women fighting for our lives, for health care rights, for our civil rights. I learned how to protect myself from AIDS. And I learned what to expect from myself. I learned to rise above, because we were so loathed by the community and the world. We forget that. … Had I not joined ACT UP in 1987, and continued to this day to be a card-carrying ACT UP member, I would be dead.”

ACT UP today — and its legacy

While most ACT UP chapters have disbanded, a few are carrying on. The Boston chapter has been revived and recently protested Fenway Health’s decision to stop providing hormones and puberty blockers to transgender patients under 19 to avoid losing federal funding. “Whether under the banner of ACT UP Boston or another group, it’s clear we need a consistent, organized platform to coordinate a sustained fightback for the transgender community as well as fight for more resources for HIV Prevention and Treatment,” says a post on its Facebook page.

ACT UP members in New York are campaigning against Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s anti-science views, plus the Trump administration’s cuts to medical research and Medicaid. They also are pushing for passage of the New York Health Act, which would create a statewide single-payer health care system. They have participated in protests against the war in Gaza as well.

Some ACT UP activists went on to channel their passion into more mainstream arenas. “I’m continuing to do the same things, but from a different venue,” Mike Shriver, then policy director for the National Association for People With AIDS, said in the 1997 SFGate article. "The idea that you lose the fire or the gusto because you run an agency is just not true. … Passion doesn't mean chaining yourself to a fence. Passion means getting money and programs to people with AIDS.”

Chicagoan Justin Hayford found ACT UP wasn’t for him, but he saw its value. “I went to one ACT UP meeting, and I couldn’t stand it because it was such active democracy that I was like, I guess I’m a totalitarian at heart,” he told Chicago Magazine in 2020. “I wanted more order. But I was thrilled with what they were doing: chaining yourself to the CDC, closing down the Golden Gate Bridge. So I thought, I’m going to work over here, schmoozing the executives and officials and people writing policy, while they’re outside screaming, which they’d better do, because they won’t listen to us unless they fear their building’s going to burn down. You need both.”

Ann Northrop expressed a similar view in her Advocate podcast interview, regarding not only AIDS but LGBTQ+ rights and social justice in general. "The movement needs people coming at people in power from every angle," she said. "We need lobbyists. We need people on the inside working. We need people who are donors. We need people who will write their members of Congress, but we need people out in the streets who will raise issues honestly and directly and shame people in power when they don't do the right thing."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.