Marvin Gaye is playing inside Donna Aceto’s cozy apartment in the West Village. “A day without Marvin Gaye is like a day without sunshine,” she says from her living room, as New York City is in the midst of a grueling June heat wave. Inside her one-bedroom apartment, the bookshelves are almost overflowing with memories — the trinkets, knickknacks, and family photos serve as a sort of museum to her life here in the Village.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

This is the apartment where Aceto has lived for 35 years, after moving out of Brooklyn in 1990, when she was working as a retail municipal bond trader on Wall Street. Moving to the West Village put her closer to her job and to the lesbian bars she frequented. She ultimately left that job to pursue a career in freelance photography. Her apartment remains a convenience for her. But the neighborhood has changed.

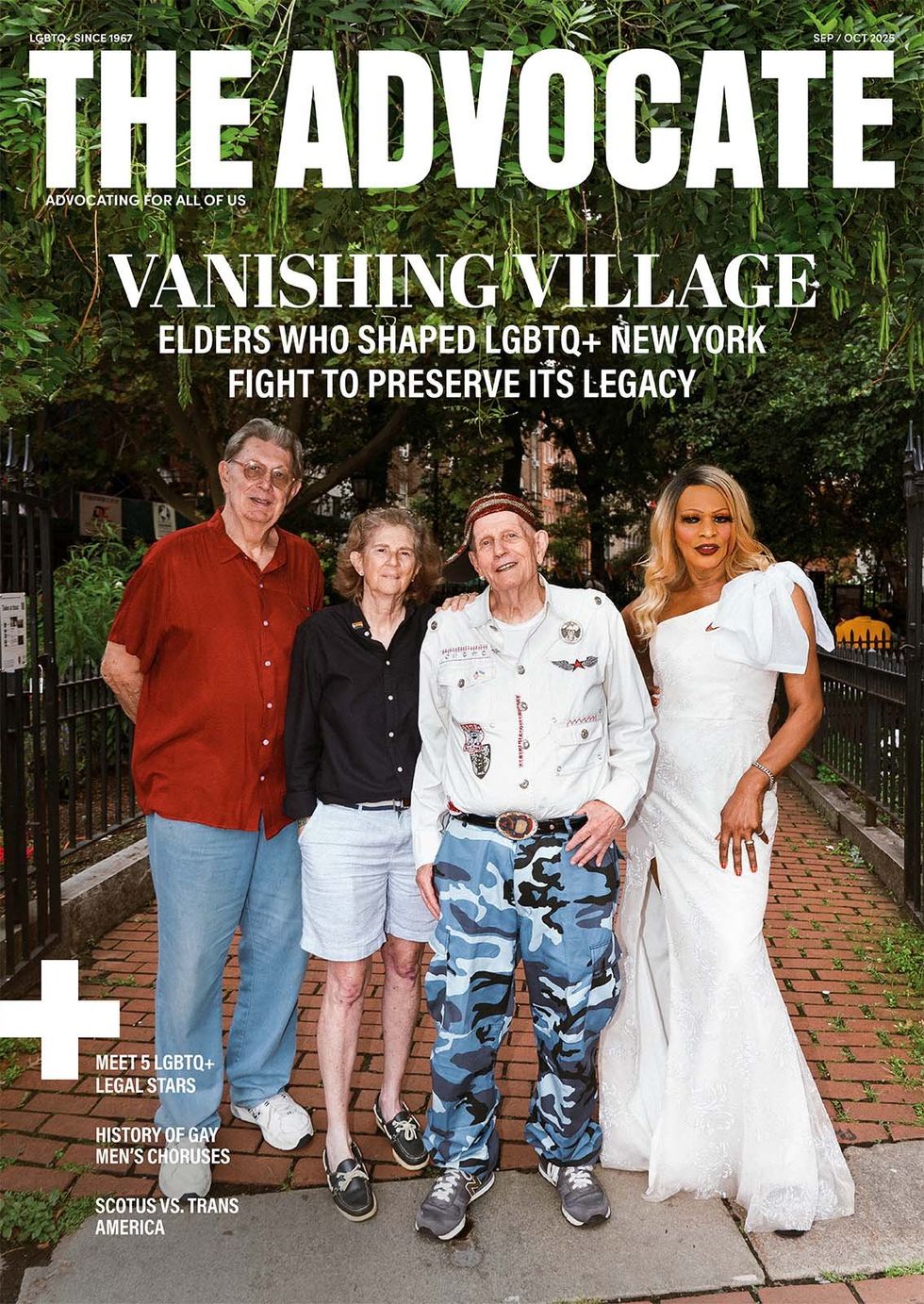

“It’s gotten very straight,” Aceto says of the West Village, known as a queer haven since before the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement was sparked at the neighborhood’s Stonewall Inn in 1969. Aceto’s observation is well-documented; a May article in New York Magazine detailed the rapid rise of “West Village girls,” the throngs of mostly straight young women who have moved into the historic neighborhood.

Over the years, the West Village has become increasingly less viable for the queer elders who planted roots in the apartments they’ve been in for years, as developers build new apartment houses and charge astronomical rents that then drive up the prices in the neighborhood. Those prices are something only young, predominantly white, affluent people can afford. On top of that, expensive restaurants, cafés, and bars move in and steal customers from small businesses (many of which are queer-owned) and push them out as well, effectively de-queering the neighborhood.

This gentrification of the West Village threatens to displace many of the queer elders central to the nation’s LGBTQ+ history, according to interviews with residents and historians. But the fight to preserve the neighborhood’s rich history continues.

“I miss the old places. I miss the things that used to be here. I miss the reasonable restaurants,” Aceto says. “There were a lot more gay bars and lesbian bars. Nobody is going to be moving here that I’m hanging out with.” Aceto has considered leaving the Village for a more affordable neighborhood but hasn’t been able to go through with it. “It’s my home. I love it. I’ve been here forever, and I’m not letting anyone chase me out,” she says.

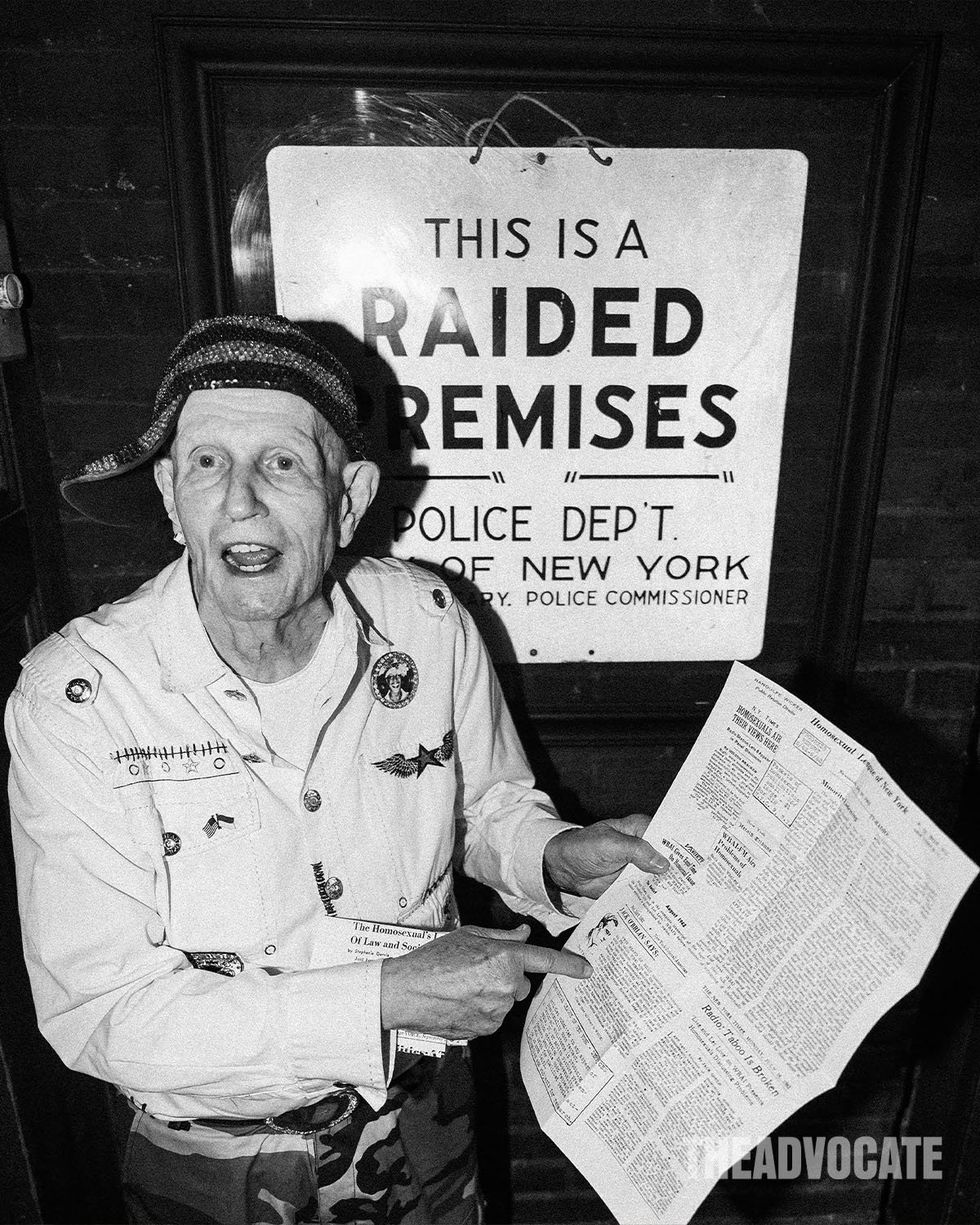

But not everyone has been able to stand their ground. Randy Wicker, a queer rights activist and author, spent 41 years living or working in the East and West Village. Beginning in 1974, he operated one of the many gay businesses that populated the streets — an antique light shop on the corner of Christopher and Hudson streets, in a space he rented for just $300 a month. In the 1980s, it was where his close friend and roommate, Marsha P. Johnson, readied for nights out.

However, things began to change in the 1980s. “Building after building was renovated. New apartments were no longer rent-controlled. AIDS took its toll,” Wicker says. “Newcomers to the area were mostly young heterosexual couples. The vibrant gay community slowly relocated northward towards Chelsea or into lofts in SoHo, where rents were cheaper in abandoned commercial buildings.” Wicker owned the antique art deco lighting shop for 29 years but decided to close it in 2003 after the rent soared to over $6,500. It was the last of nearly 30 antique shops that made up “antiques row” three decades earlier.

Even as gentrification forced people like Wicker out of the neighborhood, efforts have been made to commemorate the Village’s queer history. Where Wicker’s shop once stood, the street is now also known as “Sylvia Rivera Way,” in honor of the famed transgender activist (and former manager at the light shop). He points to the small park across from the Stonewall Inn, which is now recognized as part of the Stonewall National Monument. And Julius’ Bar around the corner is recognized as a national landmark, “because it was where organized homosexuals demanded the right to public assembly and public accommodation in 1966, laying the foundation for the legal existence of bars and restaurants catering to the LGBTQ+ community,” Wicker says.

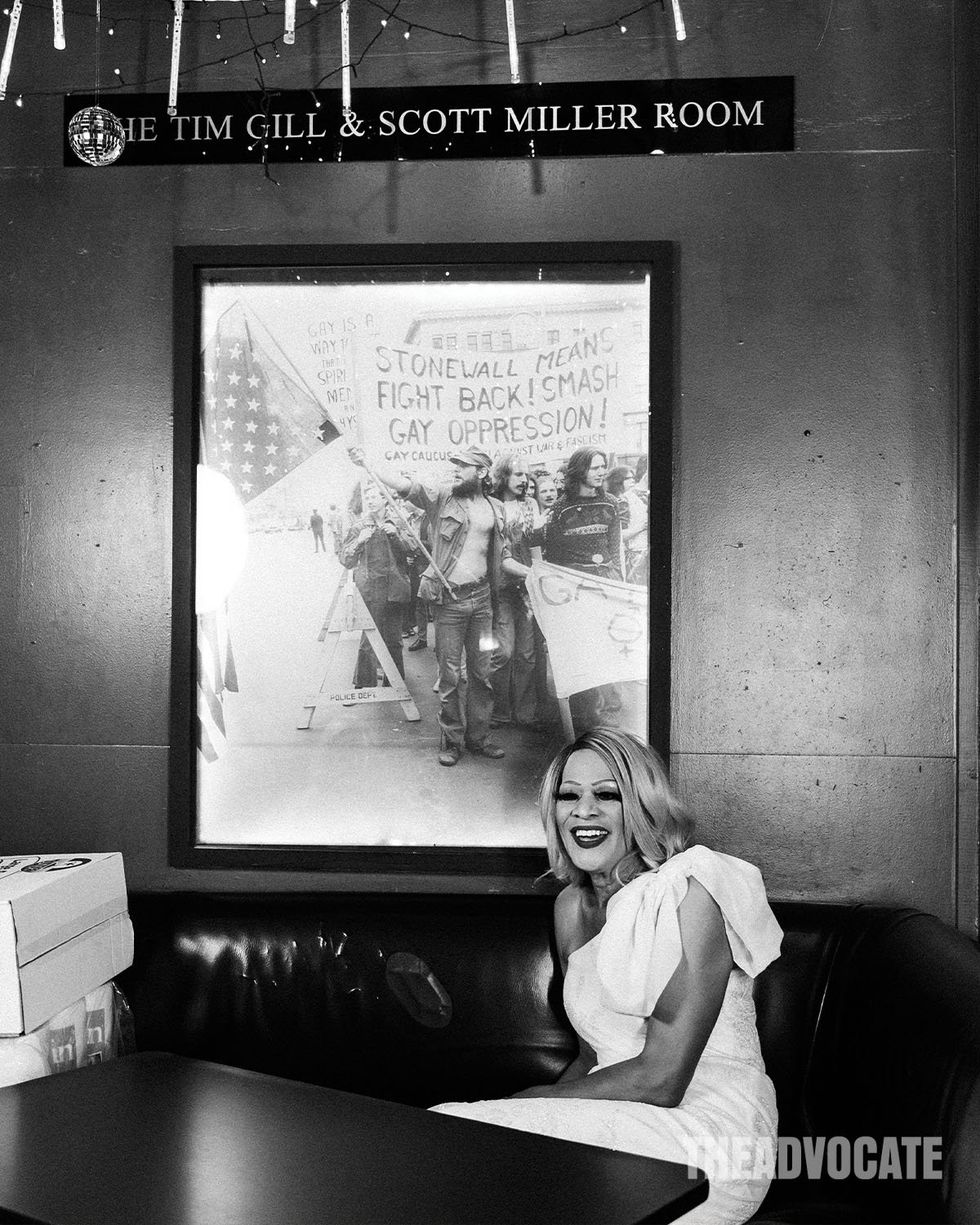

As a local performer, Miss Simone has seen the neighborhood change over the years. The West Village staple, who declined to share her age and asked to go by her performer name, moved to New York City from Detroit with the hope of becoming a fashion designer. Though she lived in Queens, she would frequently venture into Manhattan and host impromptu drag lip-synch shows in the park for tips.

“When I got to the West Village, it was just wide open,” she says. “You had all these gay kids everywhere. That’s where everybody went to forget their troubles.” But as a newer crop of young people moved into the trendy neighborhood, they had less respect when it came to being in queer spaces. “They make you feel like you’re a guest at your own party,” Miss Simone says.

The existence of queer people in Lower Manhattan began well before the ’60s, says George Chauncey, a history professor at Columbia University and author of the book Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. In the first 20 years of the 20th century, the West Village became a haven for bohemian writers and artists to live because it was more affordable, Chauncey says. That included many queer people. The extension of the subways to the Village in the early 1920s helped accelerate the neighborhood’s growth, he notes.

By the 1920s, the West Village had become the most popular gay neighborhood in the country. During World War II, New York was a major port where soldiers were shipped to the battlefront in Europe. Chauncey says they were often given 24 hours’ leave, and many of them came into the Village because it was known as the center of free love. In the 1950s, it remained a hub for artists and writers. In the 1960s, it became a neighborhood that provided solace to youth who were kicked out of their homes from all over the country, and some of these youth were among the most crucial participants in the Stonewall Riots of 1969.

Fredd E. “Tree” Sequoia is one of the last few queer elders who witnessed the unfolding events almost 60 years ago. “In the ’50s and ’60s, we had no rights,” he says. “We made friends, but I try to explain to the younger generations that … we never asked for last names.” Even today, he goes by his nickname, a preference born out of protection, as he and many others feared ostracization from loved ones should they be arrested for being at a gay establishment.

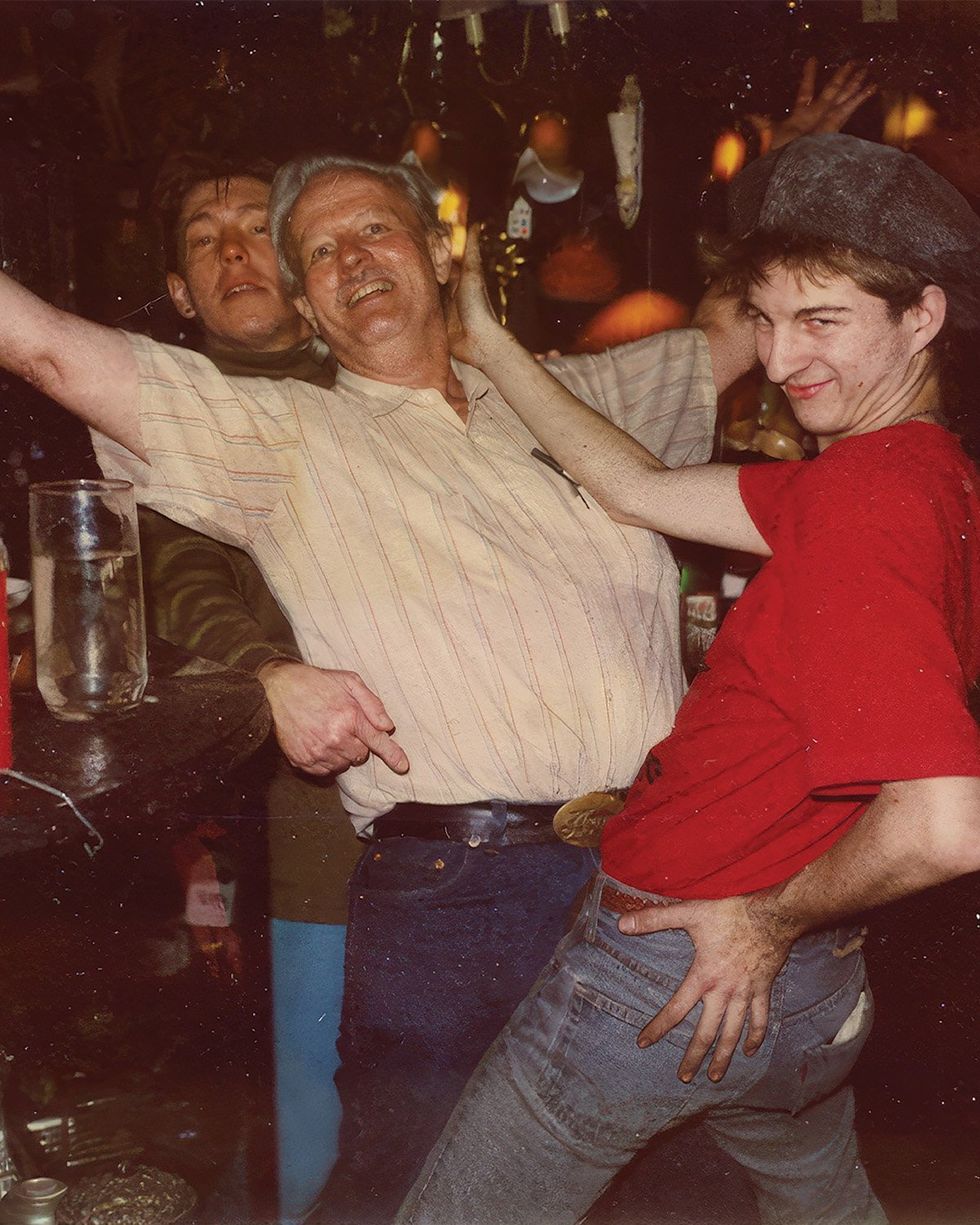

“I was dancing inside [Stonewall] when the police came in,” he remembers, “but we were lucky and got out.” The 86-year-old is a Stonewall Inn fixture, having spent time behind the establishment’s bar for 50 years — and occasionally, he still does. While the establishment remains an institution in the Village, many of Tree’s other haunts are now mere memories. “Well, there used to be so many gay bars,” he says. “There was Two Potato [a gay bar on Christopher Street]. My favorite was Carr because they had a jukebox with all the old ’40s singers on it.” Over the years, the hub of queer nightlife flowed from the West Village to other neighborhoods. “And then they went to Chelsea, and then from Chelsea, they went to Hell’s Kitchen,” Tree says.

Preserving this history is the mission of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Since 2015, a team of historic preservation professionals has built a digital collection of historical documents on key sites related to queer New York City history. Ken Lustbader is one of the organization’s project directors, working to register historic sites on the state and federal levels. Among those is Julius’, the site of the infamous April 1966 “sip-in” organized by the Mattachine Society, an early queer rights organization. Though many of the locations are still preserved — some “are usually already in historic districts,” Lustbader notes — some sites have been demolished. Paradise Garage is one example. Once the crown jewel of New York’s queer nightlife, beginning in 1977, Paradise Garage at 84 King St. in Hudson Square was torn down in 2018. The club served as a cultural incubator for nearly a decade, earning recognition as the birthplace of today’s nightclub scene.

Sadly, the threat to preserving queer history goes beyond the whims of New York real estate. Since Donald Trump’s return to office, his administration has made concerted efforts to erase queer visibility from the public sphere, including scrubbing historical references to trans identities on the Stonewall National Monument’s website and removing Harvey Milk’s name from a Navy ship. Federal funds for additional research needed to list famed civil rights figure Bayard Rustin’s Chelsea residence as a historic landmark have been frozen under the Trump administration. “Queer history is America’s history,” Lustbader says. “By erasing our history … they are erasing us from American life.”

New York City Councilman Erik Bottcher’s district includes the West Village, Chelsea, and Hell’s Kitchen, among other neighborhoods. Bottcher understands it’s his duty to preserve the queer history embedded in his district. He highlighted his role in working with groups like the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project to secure listings for locales like Julius’ and working with historians and activists to protect sites from the Trump administration’s attempt to erase LGBTQ+ people from public history and life. “But preserving queer history also means preserving queer presence,” Bottcher says. “The West Village must remain a living archive of LGBTQ+ life.

This cover story is part of The Advocate's Sept/Oct issue, which hits newsstands August 26. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Apple News, Zinio, Nook, or PressReader starting August 14.

photography ROLAND FITZ @rolandfitz.me

videography EMILY TEAGUE @_emilyteague

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.