When Courtney Gore sat down with her Texas school district’s curriculum, she expected to find something, anything, that would justify the panic she’d been hearing for months. The warnings had been vivid and insistent: children were being “indoctrinated,” parents were losing control, and public schools had become staging grounds in a cultural war over gender, sexuality, and race. Gore, a former educator turned Texas school board member, had moved close enough to those arguments to believe that maybe there was a fire somewhere behind all that smoke.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

What she found instead was paper. Lesson plans. Objectives. Exercises in naming feelings and learning how to sit with disagreement.

“I read through all the lesson plans, and it was great things we were teaching our kids,” she told The Advocate. The materials focused on social and emotional learning, how children recognize their emotions, how they resolve conflict, and how they learn to live alongside other people. None of it resembled the lurid stories she’d been told.

Leaving Moms for Liberty’s propaganda behind

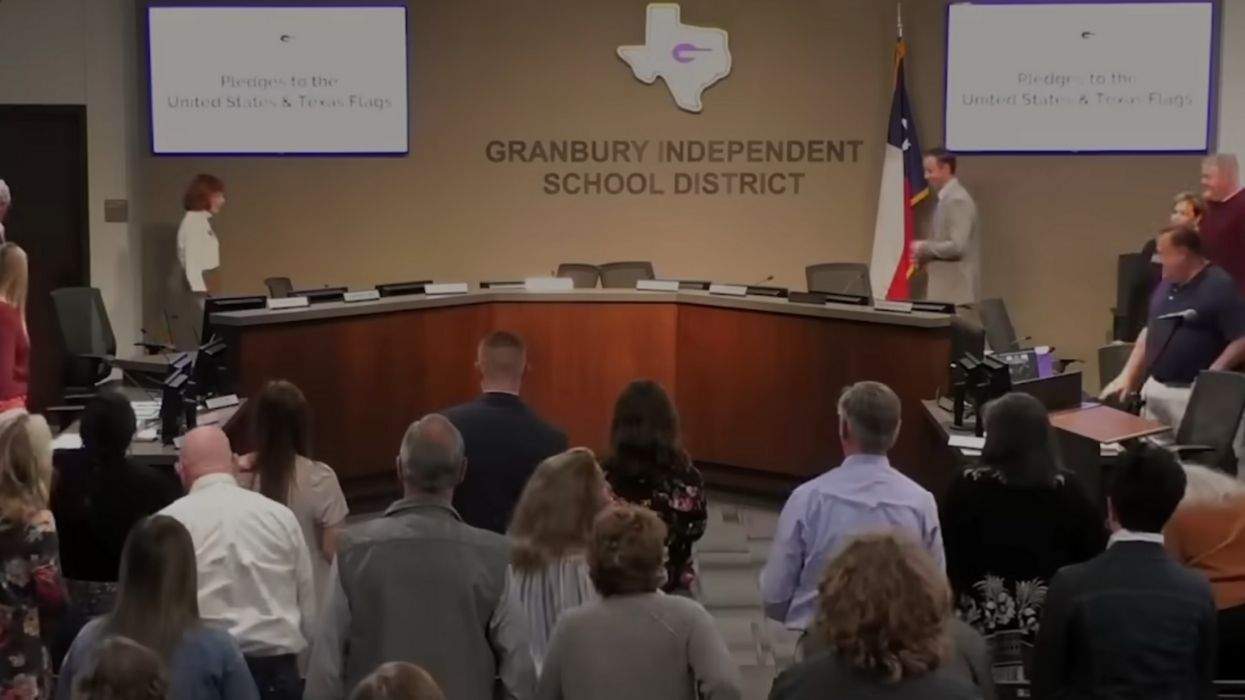

That quiet discovery, mundane, bureaucratic, almost aggressively normal, is one of the emotional hinges ofThe Librarians, a new documentary by Peabody Award–winning filmmaker Kim A. Snyder, premiering Monday on PBS. The film, which focuses on several Texas school districts, including Keller and Granbury, begins with a list: In 2021, Texas state Rep. Matt Krause, a Republican, circulated the names of 850 books for review, many of them focused on LGBTQ+ lives, race, racism, and history. But Snyder’s film is not really about lists. It’s about what happens after the list is made — about the people who enforce it, the people who resist it, and the people who get caught in between.

Related: How library workers are defending books, democracy, and queer lives

Related: Book bans in schools are more widespread than ever. Which states have had the most?

Two organizations loom large in that story. One is Moms for Liberty, a right-wing parents’ group that has become a central organizing force in book challenges and school board fights across the country. Founded in 2021, the group frames itself as a defender of “parental rights,” but it has built a national network around opposing LGBTQ+-inclusive curricula, diversity initiatives, and books that address sexuality, gender identity, or systemic racism. The other is Patriot Mobile, a Texas-based wireless company that markets itself as a “conservative” alternative to major carriers and funnels money into local school board races and right-wing causes, particularly in Texas. In Snyder’s film, they appear as infrastructure: the messaging, the money, the training, the amplification.

Gore, who has served on the Granbury Independent School District school board since 2021, is one of the film’s most complex figures. She had been drawn toward the rhetoric of “parental rights,” she said, not because she harbored animus toward LGBTQ+ people, but because she believed parents were being cut out of decisions about their children’s education. “I personally wasn’t anti-LGBTQ,” Gore said. “I was more of a pro-parental rights person.” The language she heard echoed talking points popularized by groups like Moms for Liberty, suggesting something was being imposed on children, not simply taught.

So she went looking.

Related: Book ban attempts surge to record highs in 2023

Related: 'Gender Queer,' one of the most banned books in the U.S., is getting a deluxe edition

What she found was not a scandal but a vacuum: no evidence of the claims, no hidden program lurking in the margins. When she tried to take that conclusion back to the people she had once worked alongside in conservative circles, she said, the response was swift and unforgiving. “The only way to keep people from hearing what I had to say was to try and discredit me,” Gore said.

In The Librarians, her shift reads less like a conversion than like an estrangement. The community she thought she was serving suddenly treated her as a liability. Gore describes being angry at herself, embarrassed, and then, slowly, resolved.

“I felt like I had a duty,” she said. “I knew the truth. I’ve got the evidence, and I have to say something.”

The cost was not abstract. It was social, local, and personal.

Related: Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff to tackle Republican book bans at Manhattan roundtable discussion

Snyder sees Gore as a reminder that the movement behind book bans does not rely only on hardened ideologues.

“There are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Courtney Gores,” she said— people pulled in by claims about obscenity and danger, who only later discover, if they look closely enough, that “there was no there there.” Organizations like Moms for Liberty, she argues, are effective precisely because they translate national culture war narratives into local urgency, showing up at school board meetings with binders, talking points, and the promise of community.

Gay homeschooled son confronts mom’s bigotry

Gore represents the uneasy work of unlearning, as Weston Brown represents the damage done when that work never happens.

Brown is a gay man from Texas who grew up in a tightly controlled, homeschooled environment. No television. No internet. No library visits. He moved away after leaving home and returned to advocate against the exclusionary policies taking shape in his hometown.

“The education was no education,” he said. Even books in his home were censored; pages were cut out of a human anatomy book because they showed reproductive organs. The first time he saw an explicitly LGBTQ+ symbol, he remembers, was a barista’s Pride pin at a coffee shop. He calls it “a life-saving moment” — not because it solved his troubles, but because it showed him, for the first time, that someone like him could exist in public and survive.

Related: Republicans and Democrats Clash on Book Bans in Congressional Hearing

In The Librarians, Brown, a community member, shows up at a school board meeting in Granbury, Texas, to speak in defense of books. He is not there to confront his family. He does not even expect them to be there. But in the front row sits his mother, Monica, a right-wing activist aligned with the same ecosystem of groups that animate these fights, holding up her phone and filming him as he speaks.

The camera lingers on the scene with an almost unbearable steadiness: a son talking about stories, and a mother recording him as if gathering evidence. Afterward, she follows him with her phone as he gives an interview to a local TV station. Snyder has said she’s seen this tactic before — the phone as a tool of confrontation, of social media warfare rather than connection. It is part of the same feedback loop that groups like Moms for Liberty and their allies rely on: conflict captured, clipped, and redeployed online as proof of threat.

Related: Kamala Harris defends LGBTQ+ teachers & condemns book bans at teacher labor union conference

Brown told The Advocate that he learned long ago not to build his life around the hope of changing his parents.

“I’m not here to reach my parents,” he said. “That pressure would crush me.” Instead, he speaks to the people in the room who might still be reachable: the parents who have been told that librarians and teachers are pushing obscene material on their children. “It’s a flat-out lie,” he said.

Brown openly discusses how the lack of representation nearly killed him.

“All that lack of representation did was just make me incredibly vulnerable for a very long time,” he said.

He remembers believing he was broken, defective, someone who had slipped off “God’s factory line of human creation.” He came close to ending his life. Books, he says now, didn’t just widen his understanding of the world. They helped keep him in it.

The librarian forced to carry a gun

Amanda Jones, a Louisiana librarian featured in the film who was named librarian of the year for her work during the COVID-19 pandemic, told The Advocate that the current fight over books has reshaped not just her job, but her entire life.

“I do travel with a weapon,” she said. She plans where she sits in restaurants so she can see the exits, watches her rearview mirror, and has had people follow her. “I never lived like that before, ever,” she said, describing years of harassment that have not let up.

What makes the conflict more painful, she said, is that it runs through her family and her community. Jones said she was raised Southern Baptist and Republican, in a household where loving your neighbor and defending the Constitution were core values.

“Those qualities help shape the person that I am,” she said, adding that she was taught to “champion the underdog and be the good Samaritan.”

At the same time, she said, she was raised to believe strongly in protecting the country from harm, both from outside and within.

Related: How to Fight Book Bans, According to the American Library Association's Queer President

Her mother, she said, is a retired kindergarten teacher who built Jones’ childhood around books and weekly trips to the library.

“My entire childhood revolved around the public library and reading books,” Jones said, adding that, in that sense, her current stance should not be a surprise to her parents — even if it has become a point of deep conflict.

That conflict has changed her family life in concrete ways. Jones said she has drawn firm boundaries about what she will tolerate around her daughter and about the language and attitudes she will accept.

“I will not raise my daughter around homophobia, racism,” she said, explaining that she now sees what some relatives frame as “political differences” as human rights issues. The strain, she added, was so deep that for the first time in her life she did not spend Christmas with her family.

The personal toll, she said, is both physical and psychological. She described losing chunks of hair from stress and living with what she called ongoing post-traumatic stress.

“It’s been almost four years, and this has not stopped for me,” she said. But she also said the experience has forced her to see what many LGBTQ people and people of color live with every day. “I now realize that the LGBTQ community lives like this all the time,” she said. “People of color live this way all the time, and I was so privileged. I never saw it.”

Related: ACLU Calls for Federal Probe of Anti-LGBTQ+ Actions in Texas Schools

What keeps her going, Jones said, are the students. She said she has been the first adult some young people felt safe coming out to, and that former students in their twenties and thirties still tell her they felt safe in her classroom or library. In her rural community, she said, there are far more LGBTQ kids than many adults want to admit, and many of them leave as soon as they graduate because they do not feel they can live openly at home. When students ask her for books with LGBTQ+ characters, she said, she does not interrogate them, “that’s none of my business,” she just helps them find what they’re looking for.

Jones is careful, she said, to draw a distinction between good-faith challenges and campaigns meant to erase certain people from shelves altogether.

“These kids exist. They’re real. They have emotions. They have feelings,” she said. Libraries, she said, rely on professional reviews and collection development policies, and no one is forced to check out any book. “Every book is not for every person,” she said. But removing books because the author or characters are from a marginalized community, she added, takes away everyone else’s right to read them.

She is also blunt about the emotional math that keeps her in the fight. The harassment may eventually fade for her, she said, but for the kids she worries about, the hostility does not.

“This might go away for me in four or five years or whenever,” she said. “But they have to face this for the rest of their lives, and that is what I’m fighting for.”

The documentary shows Jones at library board meetings and in public confrontations.

“I actually am a Christian,” she said, “and the tenets of my faith require me to speak up.”

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.