Grazi Chiosque works for the federal government. She believes in systems. She believes in procedure. She believes that if you follow the rules carefully enough, the rules will eventually work. What Chiosque did not expect was that following the rules could still leave her wife locked inside an immigration detention center across the country for months, not because an immigration judge ordered her removed, not because a petition was denied, but because no one in the federal government would take responsibility for deciding her case.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

“I know there are steps that you need to follow,” she told The Advocate. “But my greatest frustration is that we followed all those steps. And I feel like we did a little bit over and beyond those steps.”

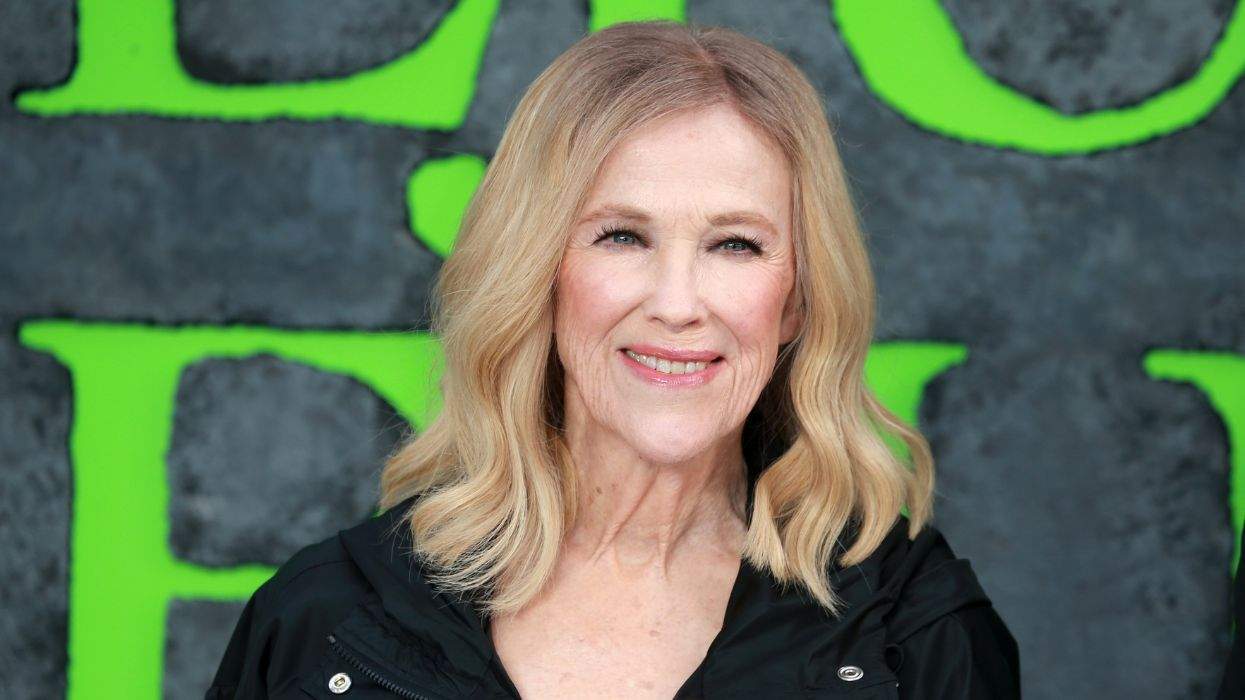

Xiomara Suarez and Grazi Chiosque

Grazi Chiosque

Chiosque, 29, lives in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and works at the Social Security Administration, where she’s been for going on four years. Her wife, Xiomara Suarez, 28, is a Peruvian national in the country legally, who is currently detained at the Adelanto Immigration and Customs Enforcement Processing Center in Southern California. The two women married in February and filed in May to adjust Suarez’s immigration status, a process that U.S. immigration law explicitly provides for spouses of U.S. citizens.

“She had an ICE appointment, like a regular check-in in September,” Chiosque said. “And that’s when she got detained.”

At the time, Suarez had no criminal record, no deportation order, and a pending marriage-based application for lawful permanent residency. According to Chiosque, ICE officials acknowledged the paperwork but told her wife that detention was simply “part of the process” and that she would need to see an immigration judge.

“I never heard about that,” Chiosque said. “You know, if you have a green card, that’s USCIS. You don’t have to see an immigration judge.” USCIS is U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

That confusion would become the defining feature of the months that followed.

A process spelled out — on paper

Under federal immigration law, spouses of U.S. citizens are classified as “immediate relatives,” a category not subject to annual visa caps. USCIS guidance states that immediate relatives who were inspected and admitted or inspected and paroled into the United States may apply for a green card without leaving the country through adjustment of status.

The process is straightforward on paper. A U.S. citizen files Form I-130 to establish the validity of the marriage. The noncitizen spouse files Form I-485 to adjust status. Immediate relatives may file those forms together or while the I-130 is pending. Visas have historically always been available in this category.

USCIS’s own instructions for Form I-485 specify that the application is intended for people already in the United States who were lawfully inspected and admitted, or paroled — exactly Suarez’s situation. Detention is not listed as a bar to filing or adjudication.

Suarez entered the United States lawfully under humanitarian parole in December 2022. In a sworn declaration supporting her asylum claim, which The Advocate reviewed, she described fleeing Peru after months of stalking and a violent sexual assault motivated by her sexual orientation, followed by repeated refusals by police to accept her complaints or offer protection.

None of that, Chiosque said, was cited as the basis for her detention.

Chiosque said the notice to appear initially alleged that Suarez had entered the United States illegally — an allegation she said was false and later withdrawn.

“They lied,” Chiosque said. “They said that she entered here illegally. And she has a parole.”

Even after that allegation was dropped, Suarez remained in custody.

“She doesn’t have anything,” Chiosque said. “They dropped that charge. They dropped that NTA [notice to appear]. They’re just keeping her because she’s out of status, but she can’t get status because she can’t do her process.”

Xiomara Suarez and Grazi Chiosque

Grazi Chiosque

December 3: when the system contradicted itself

The bureaucratic stalemate reached its most surreal point on December 3.

That morning, Suarez was scheduled to appear at 7:45 a.m. for a USCIS interview at the Los Angeles Field Office. It was the required interview tied to the spousal petition. Later the same day, she was also scheduled to appear in immigration court.

“At 7:45 in the morning, she had a USCIS appointment for the I-130,” Chiosque said. “And then the hearing was at 1 p.m.”

Chiosque flew from Pennsylvania to California to attend the USCIS appointment. At the field office, she said, she spoke directly with a supervisor.

“The supervisor guaranteed me that USCIS does not have jurisdiction because she’s detained,” Chiosque said. “The immigration judge would have to adjudicate on both.”

But when Suarez appeared before the immigration judge later that day, Chiosque said the explanation flipped.

“The judge said, ‘No, I don’t have jurisdiction on the I-130. There’s nothing I can do,” she said. “If USCIS does not want to give you an interview, contact your congressman.”

The federal government had scheduled two proceedings that canceled each other out — then refused to reconcile them.

“USCIS says it’s not them because she’s detained. And the judge says it’s not them, it’s USCIS,” Chiosque said.

Months in limbo — and a system under strain

Suarez remains detained at Adelanto. Her next immigration court hearing is scheduled for January 28. Chiosque fears it will change nothing.

“That doesn’t mean anything,” she said. “Because what if January 28, and we don’t have the I-130 approved because nobody decided who has jurisdiction?”

The toll has been steep.

“We thought, oh, it’s going to be a week, it’s going to be a month,” Chiosque said. “And we’re going for three months.”

She said that although the ordeal was in its third month, “it feels we’re still on the start line.” She added. “I don’t understand how that’s possible.”

Chiosque said she has spent thousands of dollars on emergency travel and last-minute flights, and that money has been short, particularly during the recent six-week government shutdown, when federal employees like her were not paid.

“I didn’t have to take a last-minute flight,” she said. “That cost me so much money. And nothing got resolved.”

The couple speaks daily by phone but has not seen each other in person in months.

“Last time I saw her was in October,” Chiosque said

Xiomara Suarez and Grazi Chiosque.

Grazi Chiosque

Inside Adelanto, Suarez has described conditions that are degrading and isolating.

“There’s mold in the food,” Chiosque said. “You don’t have any privacy.”

“She was put into shackles,” she added. “She told me that crying because it really made her feel like she did something that was wrong, and she didn’t.”

Álvaro M. Huerta, director of litigation and advocacy at the Immigrant Defenders Law Center, said cases like Suarez’s reflect a broader pattern. “This administration is separating and trapping families like Xiomara and Grazielli in a Kafkaesque nightmare, with the clear intention of making life so unbearable that they abandon all hope,” Huerta said. “It’s not only a policy failure, but also a betrayal of LGBTQ immigrant families who deserve dignity, safety, and the chance to thrive.”

Huerta said the consequences extend beyond individual cases. “It is un-American, and it exposes how Stephen Miller and Donald Trump are dismantling any semblance of due process in the immigration system, eroding the rule of law, and shattering public faith in our government institutions,” he said. “It is deliberate and systemic cruelty. And tragically, immigrant and mixed-status families will continue to bear the burden of this government-orchestrated trauma.”

Congressional outreach and limited leverage

Chiosque has contacted U.S. Sen. John Fetterman’s office in Pennsylvania and U.S. Rep. Laura Friedman’s office in California. She represents the district where Suarez is detained. Both offices have opened inquiries, Chiosque said, but neither has been able to force a resolution or even secure clarity on which agency is responsible for adjudicating the spousal petition.

A spokesperson for Friedman told The Advocate that they declined to comment on the case. “We do not comment on individual constituent service requests,” the spokesperson said. “When constituents ask for help, our office fights to get them the answers and action they deserve from the relevant federal agencies.”

In a separate statement, Friedman criticized the broader immigration enforcement approach under Trump. “Rather than focusing on serious criminals, Trump is targeting hardworking members of our communities who have lived here for years and are seeking a better life for their families,” Friedman told The Advocate in a statement. “Trump’s policies are cruel and deeply wrong, which is why I’m leading the No Masks for ICE Act to bring accountability and transparency back to our communities. Simultaneously, I’ll keep fighting for commonsense immigration reform to ensure that those who deserve to be in our nation have a real path towards that goal.”

The Advocate also contacted Fetterman’s office, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement for comment. None responded.

“It feels like we’re begging”

For Chiosque, the most painful part is not just the waiting, but the inversion of responsibility. She followed the rules. She trusted the system. She works for it. For a federal employee who believes in systems, that may be the most unsettling lesson of all.

“All we’re asking for is to approve the green card,” she said. “We didn’t really do anything besides follow what was asked.”

“It feels like we’re begging for something that it’s our right,” she said.

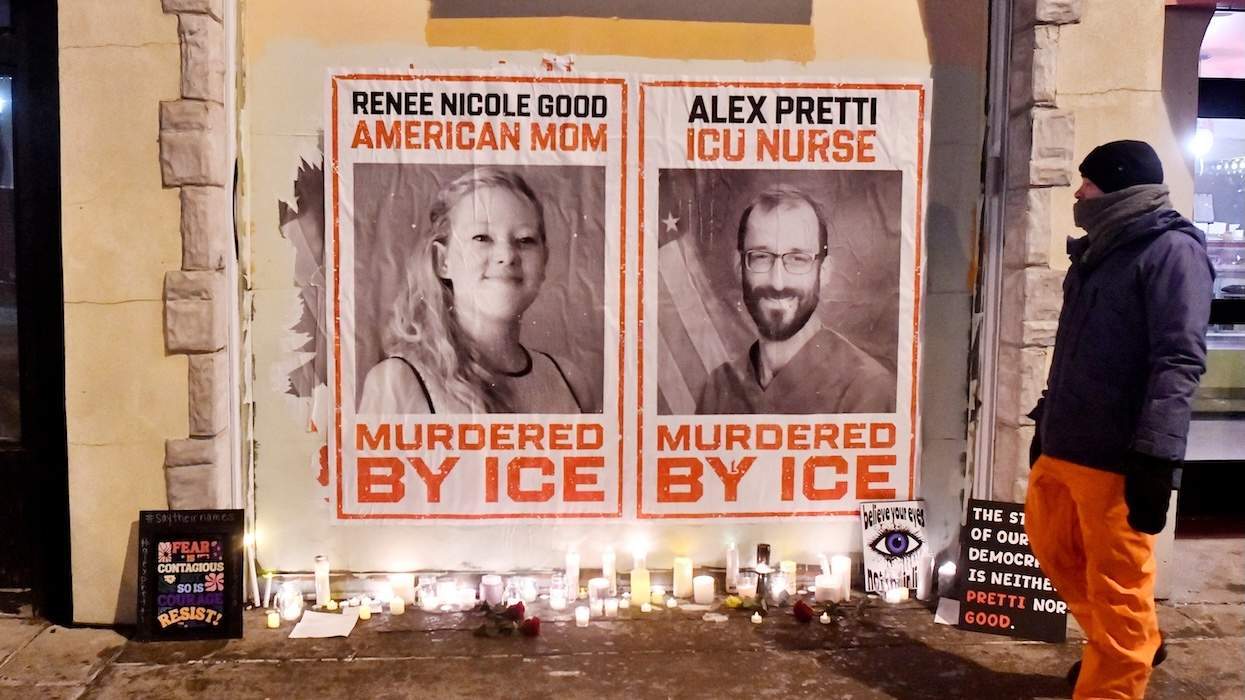

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.