This week marks another year of National Coming Out Day. So what? Many people wonder if coming out even matters anymore, when it seems the LGBT population has become so mainstream in recent years.

But an honest look into most Boston neighborhoods shows that many people, young and old, coming out is still a major undertaking with profound results. Especially in areas where racism and poverty have taken their toll, residents often feel forced to choose between their race and sexual identity. Standing up for all of yourself can put you at high risk of homelessness, violence, and problems with school and work.

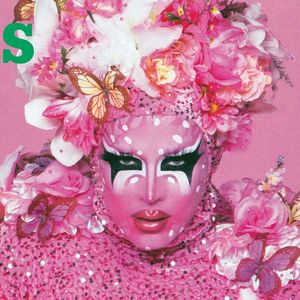

Twenty-five years after the queer theater company I founded, the Theater Offensive, began putting on shows, we have doubled down on the power of being out in our neighborhood. "OUTness," as we call it, is a tool to break down personal isolation, shake up the status quo, and build a grassroots movement for a thriving, safe, and equitable city. To that end, LGBT theater is more necessary than ever.

In 2009 the Theater Offensive brought together a group of community members, collaborators, audience members, artists, and youth from our Boston neighborhoods to grapple with the relevance of queer theater in a rapidly changing urban landscape. One evening, during the rehearsal of our youth theater troupe, an 18-year-old Haitian girl from Mattapan uttered words that became our call to action.

"Why should I have to take two trains and a bus just to be who I really am?" she asked, referring to leaving her neighborhood in rider to interact with the LGBT arts community. "I want to be out in my own neighborhood!"

We believe strongly that this is reflective of the real issues we are having in our community: Racism, poverty, violence based on bigotry and hate of our neighbors because of who they are. After that young woman's declaration, we started focusing our work intensively on our local neighborhoods of Roxbury, Dorchester, South End, and Jamaica Plain. We started putting on shows in the places where folks were least often choosing to travel to the theater district.

We worked directly with residents of those neighborhoods to create something together. The ideas was for all of us on each block to be out in all aspects of ourselves -- our gender, our sexuality, our culture, and our race -- all at the same time, without having to choose one identity at the expense of the others.

Judging from the census data and our mailing lists, we've found it's nearly impossible to find a single Boston block that doesn't have someone LGBT living on it. And according to Richard Florida's game-changing book The Rise of the Creative Class, when those neighbors are closeted, everyone in the area suffers. "Out" LGBT culture is one of the single most consistent indicators of a city's or neighborhood's ability to thrive.

Yet many of Boston's neighborhoods still remain scary places to come out as a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender person. Our approach aims to change all that -- and it's working. LGBT people from every neighborhood are coming to our shows.

Now several years into our "OUT in Your Neighborhood" strategy, we have learned so much from folks in Boston's neighborhoods. Many of the changes took some tough adjustments. We haven't had a review in TheBoston Globe in five years. Ticket income has all but evaporated because 95 percent of our shows are now free. Our actors have to ask whether the venue we'll perform in at night has a roof or not. Or a bathroom.

But what isn't hard to adjust to is the connection we now feel with our neighbors. Our audiences have grown each year, packed into parking lots, backyards, schoolrooms, churches, or living rooms, until they've far outnumbered the audiences we used to put into conventional theater seats. The majority of the folks who come to our shows haven't seen a single other play in the previous year.

You could say that we're creating new theatergoers. I'd argue that we're changing the definition of what a theatergoer is.

The biggest surprise result of our change in strategy is that abandoning the conventional theater business model has helped us find a new one that works much better for us. Our community doesn't view us as a company that "has a show in a theater with an intermission." Rather, our community says they view us as a collaborator in making sure our neighborhoods are more vibrant and thriving for everyone.

Racism remains Boston's number 1 hot-button issue, causing astounding disparities in everything from health care and education to theater attendance. Can queer theater make a difference? Yes. And 93 percent of people of color who saw our work said they'd recommend it to their friends.

Did seeing a show on the street in Roxbury or in a Dorchester kitchen have a cultural impact? Yes. And 83 percent of those who saw the shows said they now better-understand the LGBT experience and would make more supportive choices in the future.

So this Coming Out Day I'm thinking of the young man who stood up after one of our performances and said, "Every time I walk into a room I have to look around and decide which part of me to allow out. Will I turn on the gay or the black part of me? It's so liberating to be in a place where I'm just being myself, my whole self."

ABE RYBECK is the founding executive artistic director of the Theater Offensive, which is celebrating its 25th year of LGBT theater by artists of color in Boston.