Editor's Note: This story is part of our series, Unsolved, Retold: The LGBTQ+ Cold Case Files, which investigates unsolved murders of queer people across the U.S. Find out more about the series.

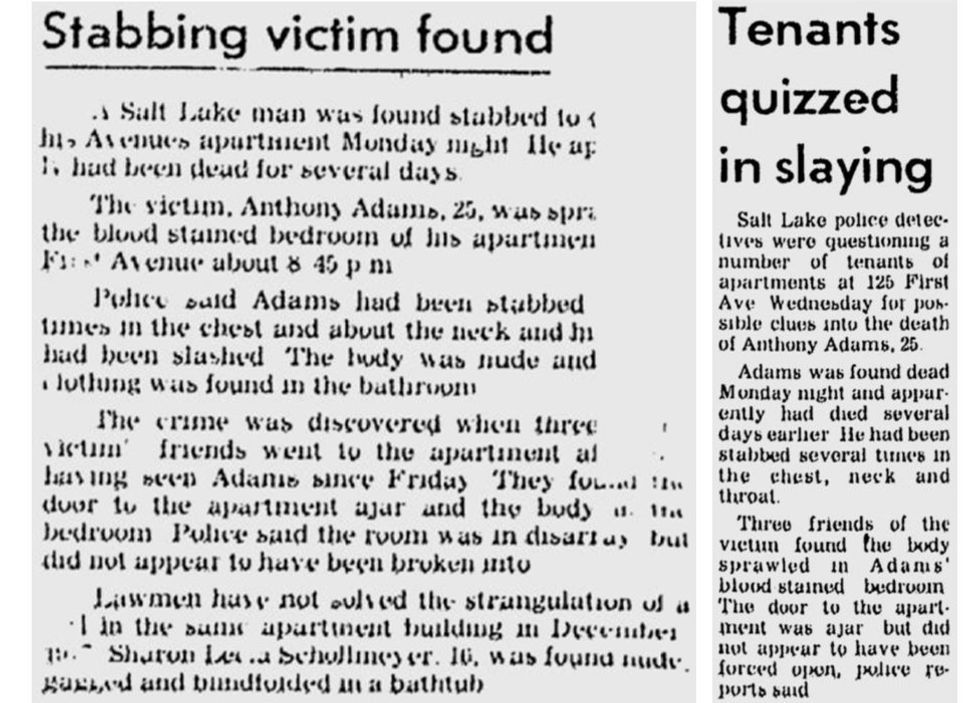

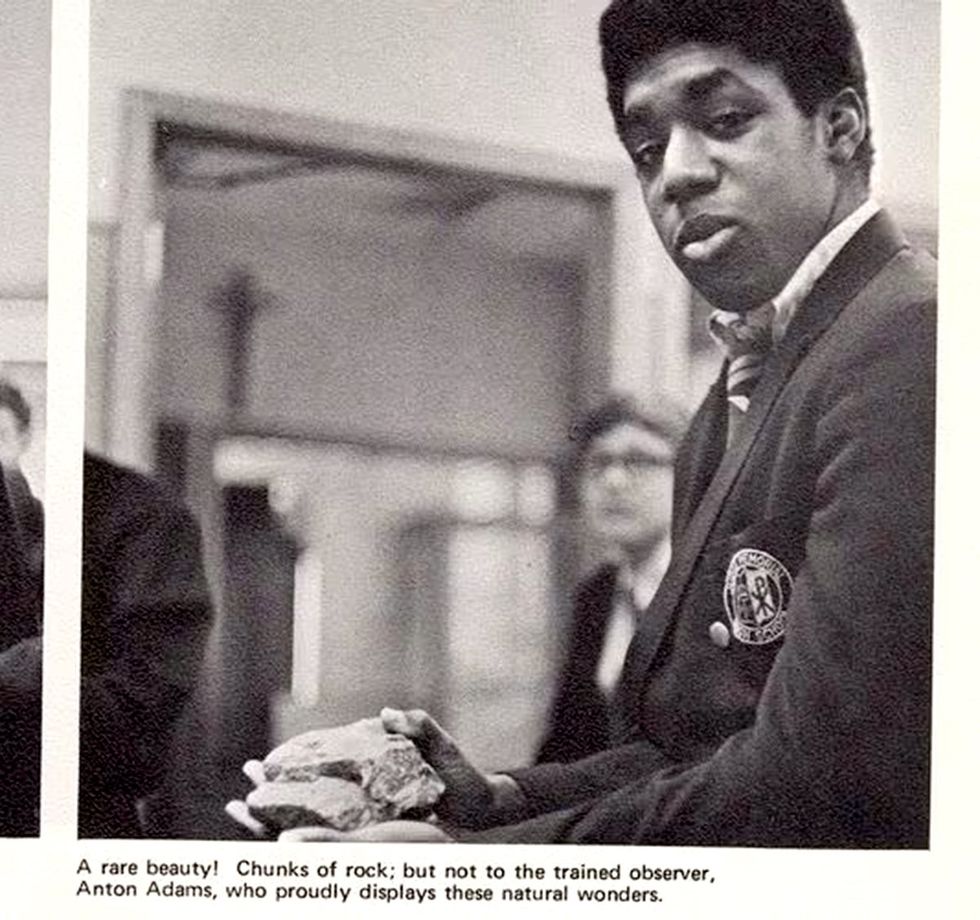

On Nov. 30, 1978, gay rights activist Anthony Adams went missing. The 25-year-old was found murdered three days later in his Salt Lake City apartment.

Adams’ case remains unsolved 45 years later, but there is information that could help police in Utah – if they could locate it.

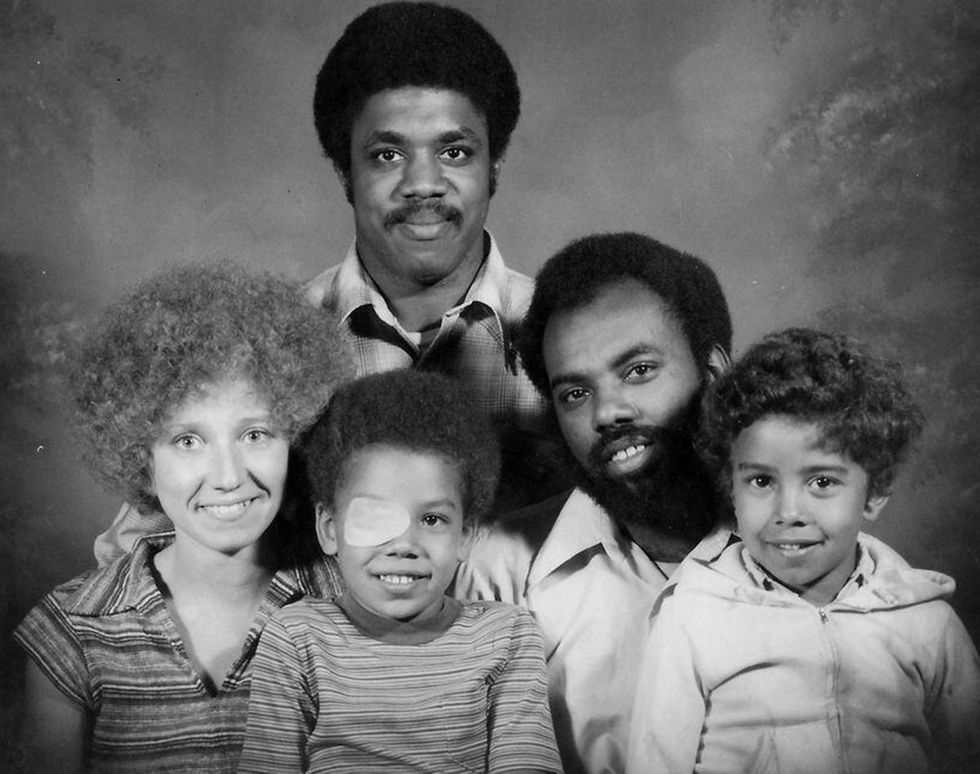

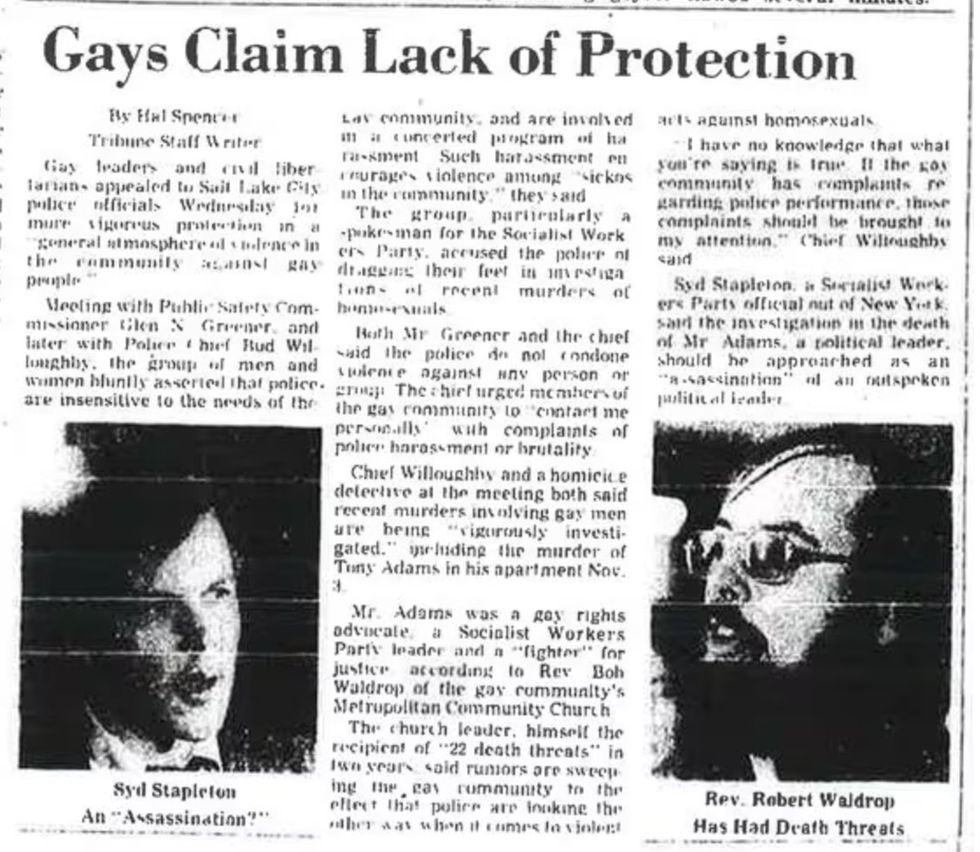

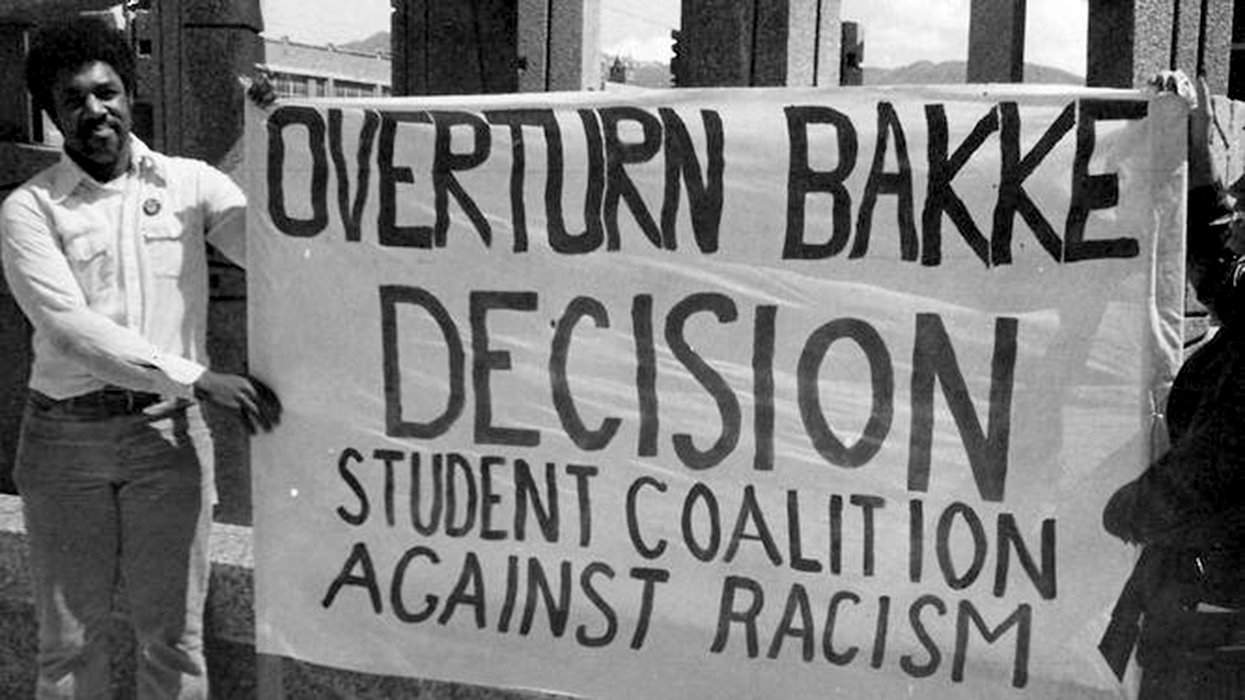

Adams was a prominent member of a Salt Lake City chapter of the Socialist Workers Party and had failed to appear for a rally, which prompted concern from fellow participants. Syd Stapleton, a member of the SWP’s New York chapter, in 1978 called Adams’ killing an “assassination” and claimed he was murdered for his sexuality and politics.

Adams was found stabbed to death in his apartment by two friends who’d grown concerned that he’d been missing for several days. Cash was missing from his wallet, but whether that indicated a robbery was unclear. Police deduced Adams had been stabbed repeatedly in the chest, throat and neck. They theorized the attack began while he was in the bath, and that Adams then struggled in the bathroom before making his way into the bedroom, where he died.

Salt Lake police heard in interviews with locals that Adams was last seen up to three days before his murder by an acquaintance, who spotted Adams at Salt Lake City’s Comeback Bar. To this day, there are no suspects.

What happened to the evidence?

The weapons used to murder Adams were left at the scene. Redacted case details recorded by the SLCPD and archived by the U.S. Department of Justice noted that “investigators found a large, wooden-handled butcher knife stained with blood on the top of a pile of sheets” in Adams’ bedroom.

Adams was attacked in multiple locations throughout his apartment, and possibly with multiple weapons: Upon a second walk-through, investigators found a “paring knife in the [kitchen] drawer that appeared to have dried blood” also.

These knives remain the linchpin that could turn the entire murder investigation around.

And yet, the evidence they may have contained is nowhere to be found more than four decades later. Somehow, in the course of sending the blood on the knife to the state’s toxicology center and back to the Salt Lake City Police, the sample went missing.

Chris Reilly, a current professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Utah told The Advocate, “We looked for any records, but we’re not able to find anything. It’s been a long time.”

Reilly added that he asked staffers at the University to trawl its archives to see if the sample existed. “We could not find a record for it, but I do not recall if that was because we did not have records for samples from that long ago or if there was nothing there that fit the description,” he added.

Adams died before the use of forensic DNA analysis in crime scene investigations became common, but if this evidence in his case were located, it could be cross-referenced with current national databases.

The most recent update in this case came in 2020 when the SLCPD matched a fingerprint from Adams’ apartment to a homeless girl, Mickey Henson, who was 16 at the time. But Henson died in 2004, and there is no other evidence linking her to Adams’ murder, making her a likely houseguest and unlikely suspect.

But how did crucial evidence that could lead to a murder conviction and justice for Adams’ family go missing? The answer lies partly in the way Salt Lake City used to process its forensics.

In 1983, the state of Utah opened its own crime lab – three years before the widespread use of forensic DNA profiling. But prior to that, the University of Utah’s Center for Human Toxicology was responsible for testing and handling evidence. The Salt Lake Tribune reported in 2018 that while the standard was for the university to return evidence to police after processing it, Salt Lake City Police Det. Greg Wilking claimed there was “no record of any stuff coming back from up there” in Adams’ case.

Did police do enough?

Wilking is pleading for answers from his own department.

“We just want to know what happened… if anybody has any idea where this stuff went,” he told the Salt Lake Tribune five years ago.

The Tribune also interviewed former workers at the university’s toxicology center who confirmed that at the time the only tests they could do was confirming that the blood on the knife matched the victim – via blood type, and also toxicology analysis.

Dennis Crouch, another technician who worked at the center in the late 1970s and early 80s, also told the Tribune the center didn’t have any formal agreement with police to test evidence and wasn’t in the habit of storing it. Further, Bryan Finkle, the former director of the center told the Utah Investigative Journalism Project that the lab never dealt with physical evidence, only toxicology, so it was unlikely they ever had the knife in their possession.

It’s unclear how this crucial evidence was mishandled or lost in Adams’ case. Both the SLCPD and the University of Utah’s toxicology center didn’t immediately return The Advocate’s request for comment.

But activists in Salt Lake City’s LGBTQ community at the time claimed police didn’t do enough. In a 1978 Tribune article, Clemens Bak with the Socialist Workers Party said law enforcement wasn’t “pursuing this case with the attention which a political crime of this type would merit,” because Adams was gay.

What’s more, the murder of Adams – and another gay man, Douglas Coleman, who was killed on Nov. 30, 1978 – shattered any feeling of safety the Salt Lake City gay community may have had at the time. Local historian and gay activist Ben Edgar Williams told the Salt Lake Tribune, “We were a very vibrant community until Tony Adams’ murder and that sent a lot of people right back into the closet, slamming that door.” He added, “not until 1981, ’82, did things start to pick up again.”

In June 2020, Karla Dobinski, an attorney for the U.S. Justice Department’s civil rights division wrote there still wasn’t enough evidence to identify Adams’ killer.

Have a tip about this case to share with law enforcement? Contact the Salt Lake City Police Department at 801-799-3000.

Unsolved, Retold: The LGBTQ+ Cold Case Files:

- What Really Happened to Marsha P. Johnson?

- Nearly 30 Years Later, Lesbian Couple's Murder in National Park Remains Unsolved

- Police Questioned a Prime Suspect in a Utah Gay Man’s Murder. Why Is the Case Still Cold?

- 45 Years Ago, Gay Activist Anthony Adams Was Murdered. Utah Police Are Still Missing Evidence

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.