December 30 2005 11:48 AM EST

CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Catherine had already buried two sisters because of AIDS when she was diagnosed with the dreaded disease. After doctors broke the news, she stopped eating. "I thought that was the end of my life," she said.

Three years later, the bubbly young woman in a floppy sun hat is sharing her marriage plans with fellow patients as they wait for medicines that are bringing new life to one of the countries worst-hit by HIV. In 2002, Botswana became the first African country to offer free treatment to all who needed it. With more than one third of adults infected, many doubted it could fulfill the promise.

But the largely desert nation now has half the estimated 110,000 people in immediate need on life-prolonging antiretroviral medicines, showing that treatment is possible on the world's poorest continent.

"If HIV was left to take its course, this country would be literally destroyed both economically and socially," said Segolame Ramotlhwa, operations manager for the national treatment program dubbed Masa, or New Dawn. "Not treating is not an option."

AIDS has ripped through sub-Saharan Africa, killing 2.4 million people this year alone, according to United Nations figures. In Botswana, life expectancy has plunged to 39 years, AIDS patients overwhelm hospital wards, and funeral homes offer 24-hour service.

Medicines that have turned the disease into a manageable chronic condition in wealthier nations remain out of reach for most in Africa, home to more than 60%of the estimated 40 million people globally infected with HIV. The cost is prohibitive, and few countries have the infrastructure to dispense them on a large scale.

Botswana, which is slightly smaller than Texas, has the advantage of a small population of 1.7 million. Diamonds have made the country comparatively wealthy, and most people live within five miles of a clinic.

But health minister Sheila Tlou says the most important difference is Botswana's commitment to fight the pandemic. Its pledge to provide treatment drew critical support from donors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and major pharmaceutical companies, but the government is paying more than 90% of the cost itself.

"African countries say they have no money, but if a war is brewing, in the blink of an eye, that money would be there," Tlou said. "So you need that commitment. Instead of spending money on Cadillacs, put money where the people are."

The massive treatment effort is straining limited resources, though. Development funds have been diverted to health, which accounts for one quarter of the national budget. Some 52,000 patients are being treated free at 32 sites nationwide, while 7,300 others obtain their medicines privately.

The results are visible. Patients who once arrived in wheelchairs and on stretchers now walk to clinics. Others believed to be on their deathbeds are back at work.

The treatment is complicated, and missed doses can cause resistance to build. But churches and other groups help ensure patients have a "buddy" to support them, and doctors say the rate of adherence tops 85%.

The availability of treatment also is encouraging more people to get tested on a continent where stigma remains high.

Catherine was rail-thin and covered in sores, but she waited two years to find out if she had the virus that killed her siblings. "That time, there was no treatment, so I didn't want to check," said the mother of two, still too ashamed to give her last name. "There were many funerals because of this disease."

Authorities estimate that up to 35% of those infected here now know their status, far higher than in other countries.

Understanding of the disease also is spreading. Patients once locked in silence now chat openly with each other in waiting rooms, swapping details of their CD4-cell counts and viral loads.

But fear, ignorance, and denial still keep many away until it is too late. Catherine's fiance reminds her to take her pills but refuses to be tested himself.

When Cynthia Leshoma was first given antiretrovirals, she was so depressed that she swallowed all the medicine at once and washed it down with cleaning fluid.

When she emerged from a coma three days later, she decided to turn her life around. She quit drinking, joined a support group, and learned to take her medicine. Earlier this year she was crowned Miss HIV Stigma Free in a beauty pageant that aims to change attitudes about the disease.

"In Botswana, we are lucky because the government is offering us medicine," said Leshoma, counting out pills on a restaurant table after her cell phone tells her it is time. "People die because of stigma, not because of AIDS."

Hoping to get more people on treatment, Botswana started routinely offering HIV antibody tests throughout the health system in 2003. Now so many patients agree to get tested that doctors worry whether they will be able to keep up with demand.

More than 12,500 people are being treated at Princess Marina Hospital in the capital, Gaborone, a dry, flat city full of strip malls. Patients line up before dawn for the daylong wait to collect monthly supplies of medicine.

"If everybody who needs treatment suddenly turned up, then we wouldn't cope," said Howard Moffat, the medical superintendent.

He also said success has some downsides. Patients may not adhere to treatment plans once they start feeling better, and the infection rate could climb even higher because treatment will reduce fear of the disease.

"Botswana has shown what can be done," Moffat said. "But it will need help for a considerable time to come." (AP)

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

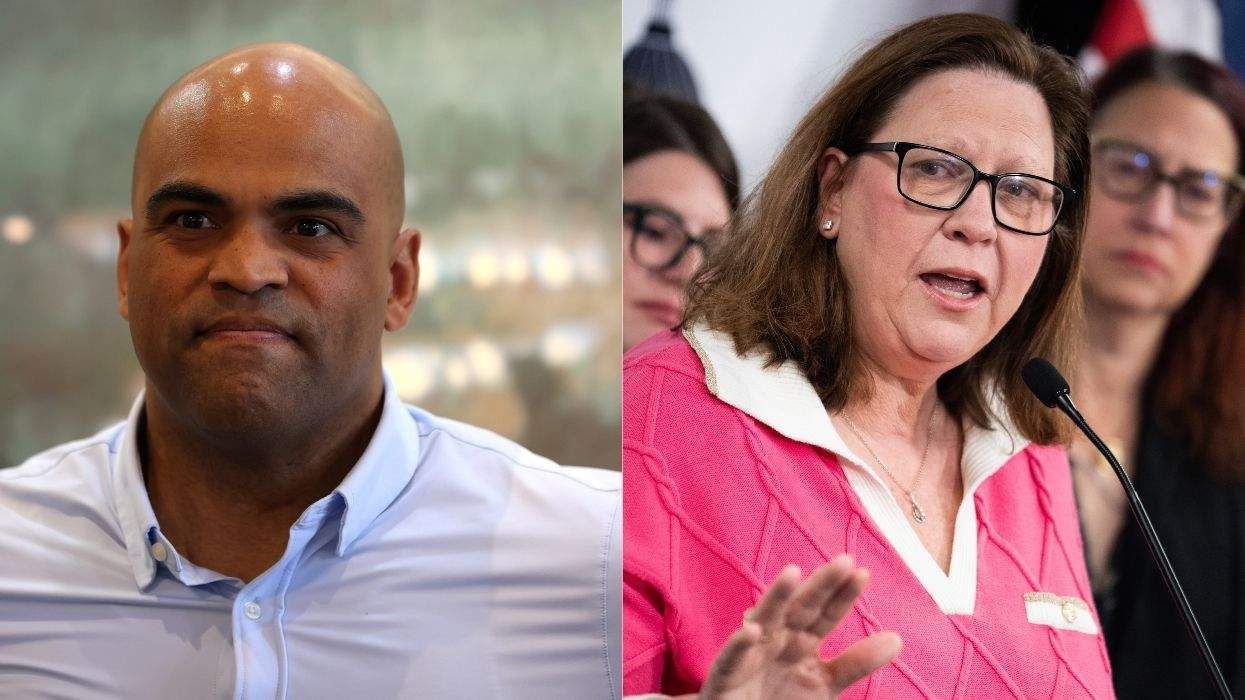

Colin Allred targets first LGBTQ+ congresswoman from Texas for House seat as Jasmine Crockett runs for Senate

December 08 2025 4:00 PM

True

There are no out NHL players. Could 'Heated Rivalry' change that?

December 08 2025 3:26 PM

World Cup LGBTQ+ Pride Match will feature two countries where being gay is illegal

December 08 2025 1:33 PM

Marjorie Taylor Greene says Trump was 'extremely angry' over vote to release Epstein files

December 08 2025 11:58 AM

Cynthia Erivo makes Golden Globes history with second nomination

December 08 2025 11:48 AM

Another University of Oklahoma instructor suspended in biblical psychology paper grading controversy

December 08 2025 10:01 AM

The next out member of Congress may be a gay man from Utah

December 08 2025 7:00 AM

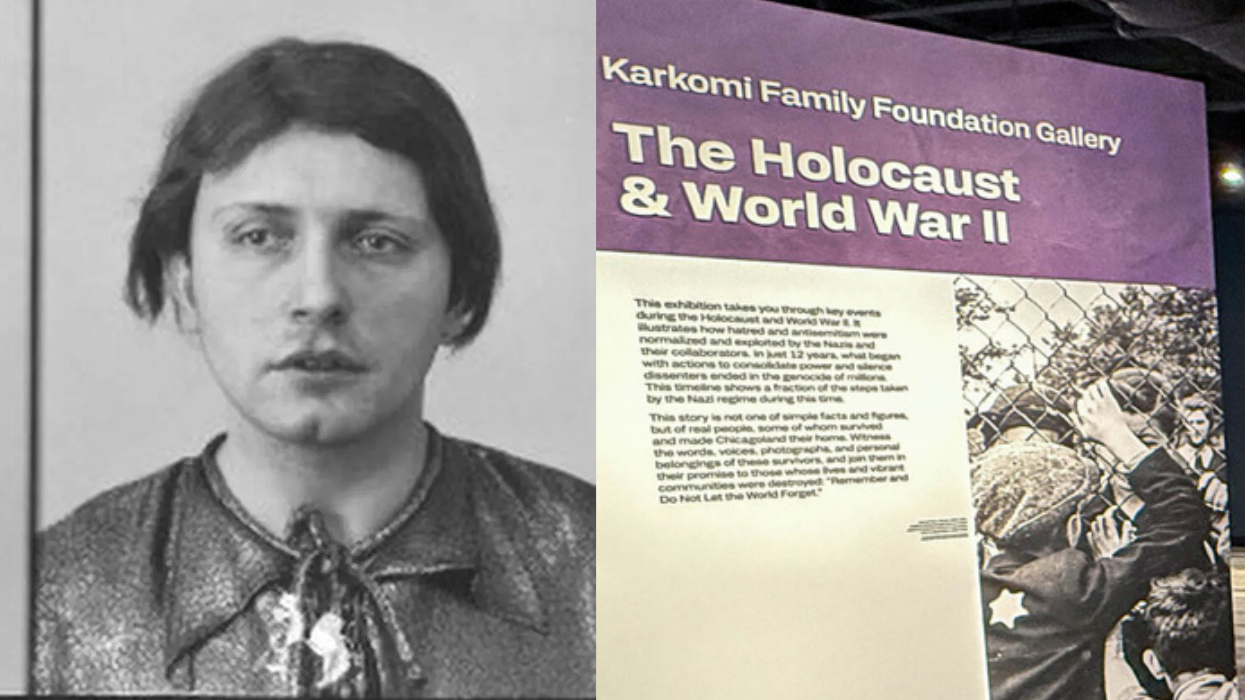

Opinion: When museums go silent, erasure speaks louder

December 08 2025 6:00 AM

HHS replaces name on transgender admiral’s official portrait with deadname in act of ‘pettiness and bigotry’

December 05 2025 8:57 PM

True

Joe Biden says MAGA Republicans want to make LGBTQ+ people ‘into something scary’

December 05 2025 8:20 PM

'Finding Prince Charming's Chad Spodick dies at 42

December 05 2025 3:45 PM

Supreme Court to hear case on Trump order limiting birthright citizenship

December 05 2025 3:01 PM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes