October 02 2006 3:23 PM EST

CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

It's an Achilles' heel of HIV therapy: The AIDS virus can sneak into the brain to cause dementia, despite today's best medicines.

Now scientists are beginning to test drugs that may protect against the memory loss and other symptoms of so-called neuroAIDS, which afflicts at least one in five people with HIV and is becoming more common as patients live longer.

With nearly 1 million Americans, and nearly 40 million people worldwide, living with HIV, that's a large and under-recognized toll.

"That means HIV is the commonest cause of cognitive dysfunction in young people worldwide," says Justin McArthur, vice chairman of neurology at Baltimore's Johns Hopkins University, who treats neuroAIDS. "There's no question it's a major public-health issue."

While today's most powerful anti-HIV drugs do help by suppressing levels of the virus in blood--so that there's less to continually bathe the brain--they can't cure neuroAIDS. Why? HIV seeps into the brain very soon after someone is infected, and few anti-HIV drugs can penetrate the brain to chase it down.

"Despite the best efforts of (anti-HIV) therapy, brain is failing," says Harris Gelbard, a neurologist at the University of Rochester Medical Center. He is part of a major new effort funded by the National Institutes of Health to find the first brain-protecting treatments.

What's now called neuroAIDS is much different from the AIDS dementia of the epidemic's early years, when patients often had horrific brain symptoms similar to end-stage Alzheimer's, unable to move or talk. They'd die within six months.

Today, anti-HIV medication has resulted in a more subtle dementia that strikes four years or more before death: At first patients forget phone numbers and their movements slow. They become less able to juggle multiple tasks.

Some worsen until they can't hold a job or perform other activities, but not everyone worsens--and doctors can't predict who will. In a vicious cycle, the memory loss makes many forget their anti-HIV pills, so the virus rebounds.

Gelbard estimates that neuroAIDS reduces patients' mental function by 25%.

If HIV patients live long enough, many specialists worry, nearly all of them may suffer at least some brain symptoms.

"They're living longer with HIV in the brain," explains Kathy Kopnisky of the NIH's National Institute of Mental Health, which is spending about $60 million investigating neuroAIDS. "And they're aging, so they're going through the normal brain aging-related processes" that can make people vulnerable to Alzheimer's and other brain diseases.

Biologically, this is a different type of dementia from any caused by Alzheimer's or Parkinson's, and drugs for those brain-degenerating diseases so far are proving disappointing against neuroAIDS.

So the government-funded attack has two fronts:

- First, to figure out which of the powerful anti-HIV cocktails are the best bet for HIV patients with memory problems.

A few of today's HIV-suppressing drugs, such as nevirapine, abacavir, AZT, and indinavir, can penetrate the blood-brain barrier, says Ron Ellis, MD, of the University of California, San Diego.

But no one knows if using those drugs instead of others will slow the brain damage once neuroAIDS symptoms begin. Early next year Ellis will begin a study of 120 such patients--at UCSD, Johns Hopkins, and Washington University in St. Louis--to try to tell, by randomly assigning them to either a brain-penetrating cocktail or different drugs.

- Second, to find drugs that protect nerve cells from the inflammation-triggered toxic chain reaction that seems to be how HIV wreaks its damage.

Topping the candidates are the epilepsy drug valproic acid and lithium, a drug long used in manic depression. Both inhibit an enzyme, called GSK-3b. The body normally makes the enzyme, but too much is poisonous. In the brain, HIV knocks that careful balancing act out of whack, leading to death of connections key to memory and other neuronal functions.

In a recent pilot study, Gelbard found tantalizing signs that valproic acid might increase brain connections in a few neuroAIDS patients, and improve their symptoms. He's about to begin a second-stage study to try to tell if the effect is real; a similar pilot trial with lithium is under way.

Seeking a one-two punch, Gelbard also hopes to soon begin a human study of an experimental drug that targets a second inflammatory protein HIV uses to trigger brain cells to kill themselves. (Lauran Neergaard, AP)

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

Joe Biden says MAGA Republicans want to make LGBTQ+ people ‘into something scary’

December 05 2025 8:20 PM

'Finding Prince Charming's Chad Spodick dies at 42

December 05 2025 3:45 PM

Supreme Court to hear case on Trump order limiting birthright citizenship

December 05 2025 3:01 PM

Women gamers boycott global esports tournament over trans ban

December 05 2025 2:55 PM

Anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes reached record-highs last year in this gay haven

December 05 2025 1:16 PM

Three lesbian attorneys general beating back Trumpism in court warn of marriage equality’s peril

December 05 2025 12:07 PM

Trump DOJ rolls back policies protecting LGBTQ+ inmates from sexual violence

December 05 2025 11:12 AM

Georgia law banning gender-affirming care for trans inmates struck down

December 05 2025 9:40 AM

Tucker Carlson and Milo Yiannopoulos spend two hours spewing homophobia and pseudo-science

December 04 2025 4:47 PM

'The Abandons' stars Gillian Anderson & Lena Headey want to make lesbian fans proud

December 04 2025 4:38 PM

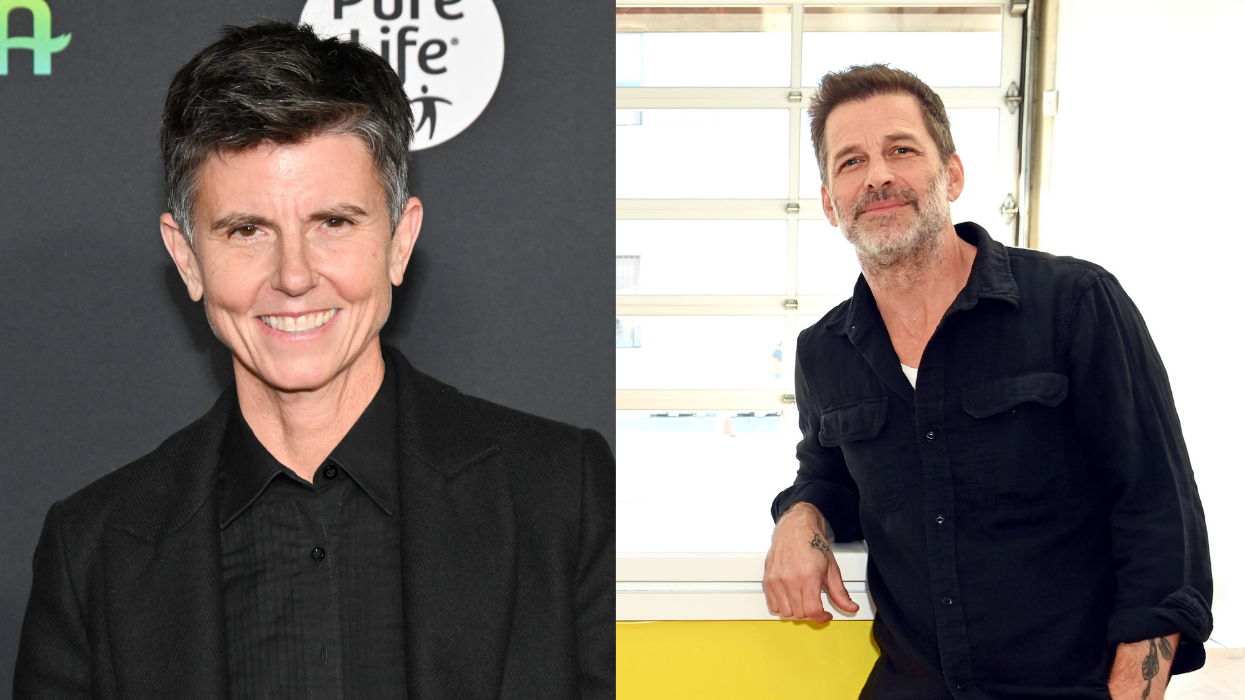

Tig Notaro is working on a 'hot lesbian action' movie with Zack Snyder

December 04 2025 4:36 PM

Cis men love top surgery—it should be available for all

December 04 2025 4:35 PM

Denver LGBTQ+ youth center closed indefinitely after burglar steals nearly $10K

December 04 2025 12:57 PM

Trans pastor says she’s ‘surrounded by loving kindness’ after coming out to New York congregation

December 04 2025 11:13 AM

Lesbian educator wins $700K after she was allegedly called a ‘witch’ in an ‘LGBTQ coven’

December 04 2025 10:59 AM

Years before Stonewall, a cafeteria riot became a breakthrough for trans rights

December 04 2025 10:50 AM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes