The Reverend

Frank Wade, a veteran of the brawling theological debates in

the Episcopal Church, said the denomination was once filled

with people like him: ''old white men.'' It was the

church of the establishment, the spiritual home of

more U.S. presidents than any other denomination.

Now the head of

the church is a woman who says the Bible supports gay

relationships. Many Episcopal priests believe that accepting

Jesus isn't the only path to salvation. And V. Gene

Robinson, who lives openly with his longtime male

partner, is the bishop of New Hampshire.

Episcopalians are

hardly alone among mainline Protestants in their

liberal turn, but they have been tested like no others for

their views. The Episcopal Church is the Anglican body

in the United States, and many Anglican leaders

overseas are infuriated by Episcopal left-leaning

beliefs.

Starting on

Thursday in New Orleans, Episcopal bishops will take up the

most direct demand yet that they reverse course: Anglican

leaders want an unequivocal pledge that Episcopalians

won't consecrate another gay bishop or approve

official prayers for same-gender couples. If the church

fails to do so by September 30, their full membership

in the Anglican Communion could be lost.

''I think the

bishops are going to stand up and say, 'Going backward is

not one of our options,''' said Wade of the Washington

diocese, who has led church legislative committees on

liturgy and Anglican relations. ''I don't think

there's going to be a backing down.''

Archbishop of

Canterbury Rowan Williams is taking the rare step of

meeting privately with the bishops on the first two days of

their closed-door talks. The Anglican spiritual leader

faces a real danger that the communion, nearly five

centuries old, could break up on his watch.

''I'm working

very hard to stop that happening,'' he told The Daily

Telegraph of London.

The 2.2

million-member Episcopal Church represents a

relatively small segment of the world's 77

million Anglicans. But the wealthy U.S. denomination

covers about one third of the communion's budget.

Within the

Episcopal Church, most parishioners either accept gay

relationships or don't want to split up over homosexuality.

However, a small

minority of Episcopal traditionalists are fed up with

church leaders.

Three dioceses

-- San Joaquin, Calif.; Pittsburgh; and Quincy, Ill.

-- are taking steps to break away and align directly with

like-minded Anglican provinces overseas.

According to the

national church, 55 of its more than 7,000 parishes have

either already left or voted to leave the denomination, with

11 others losing a significant number of members and

clergy. Episcopal conservatives contend that the

losses are much higher.

Many of the

breakaway parishes aren't waiting to see what the bishops

decide in New Orleans. They've aligned with sympathetic

overseas Anglican leaders, called primates, who have

ignored communion tradition that they only oversee

churches within their own provinces.

Primates from the

predominantly conservative provinces of Nigeria,

Uganda, Kenya, and elsewhere have ordained bishops to work

in the United States and have set up parish networks

that rival the Episcopal Church on its own turf.

Litigation over

who owns the properties has already started and will be

expensive and messy. Episcopal buildings and other holdings

nationwide are worth billions of dollars.

The fight isn't

just about the Bible and homosexuality. It's fueled by

deep differences over how Scripture should be interpreted on

a wide range of issues, including salvation and truth.

The decades of

debate turned into open confrontation when Robinson was

consecrated in 2003. A church and global communion that once

held together Christians with diverse biblical views

found itself dividing into factions, seeing little

that could unite them.

''The various

debates ... over my lifetime have been a fascinating study

in two ships passing each other in the night,'' said the

Reverend Peter Moore, a leading conservative thinker

and retired head of the Trinity Episcopal School for

Ministry in Ambridge, Pa. ''Neither heard a thing the

other said. It was clear that both groups had made up their

minds on totally different grounds, and they were not

speaking the same language.''

The outcome of

the New Orleans meeting, which runs through Tuesday, could

turn that gap into a permanent break. (AP)

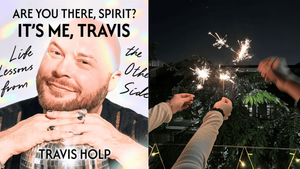

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes