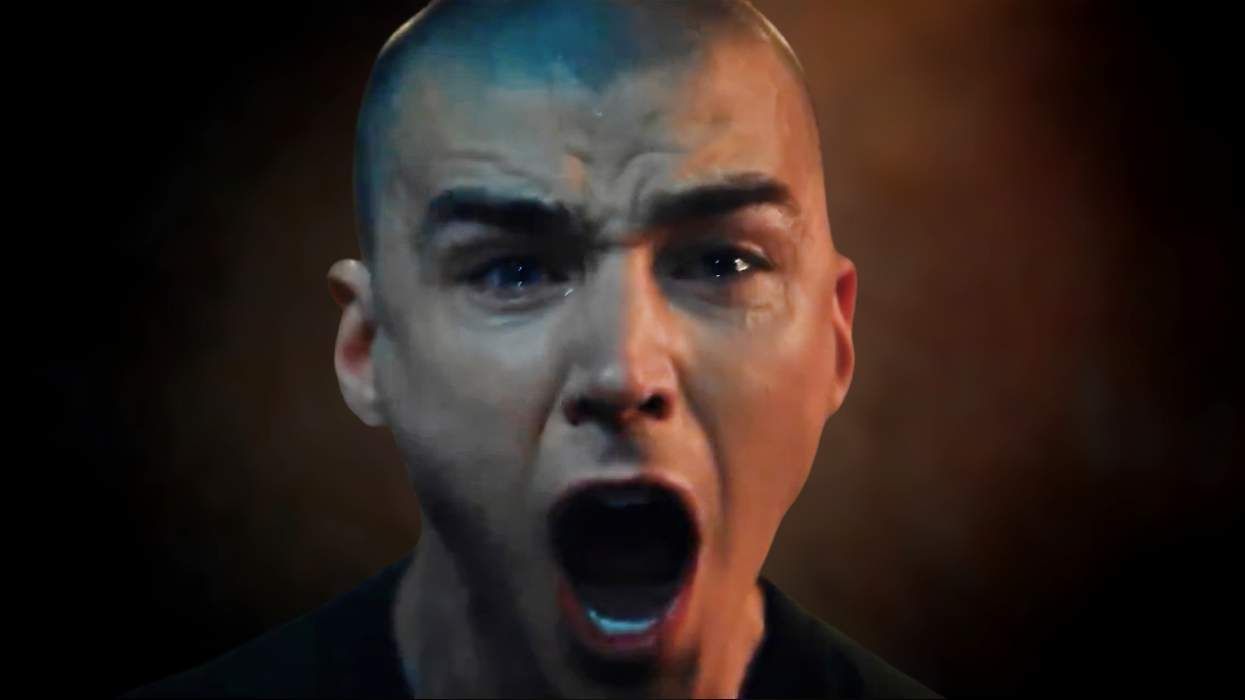

High on

prescription drugs and four days without sleep, Michael

Berke of Delray Beach, Fla., raced his Harley to

the megachurch where he had found a home.

He barged into

the church office, wearing a mesh shirt printed with

profanity. In his hands he held a picture of a curvy woman

with long red hair and pouty lips.

''This is who I

used to be,'' he said. ''And this'' -- he gestured to his

flat chest, bald head, and red goatee -- "'is who I've

become.''

He was born a

man. After a lifetime as a social misfit, he had

transformed himself into Michelle, a saucy redhead. Then,

three months ago, he had become Michael again -- with

the financial aid and spiritual encouragement of

Calvary Chapel of Fort Lauderdale.

Now he wanted to

be Michelle again, and he blamed Calvary for making him

the man he had become.

*

* *

It has never been

about sex. And the new clothes and 45 pairs of shoes

were fun but not fulfilling.

Berke wanted

friendship -- the kind women have.

He dreamed of

shopping together and gossiping in the bathroom. ''I always

admired how girls can hold hands, girls can hug, cuddle, and

there's nothing abnormal about it. It's not sexual,''

he says. ''The whole girl lifestyle is just so much

more social and caring and loving and understanding.''

His life had not

been a happy one. Kids at school teased him because he

was different, so he rebelled and often got in trouble.

Michael left home

and a strained relationship with his parents at 19,

living on the streets and flitting from job to job. He

worked as a techie for Paula Abdul and Janet Jackson,

followed by odd jobs at a veterinarian's office, at a

tanning salon, and as a nail technician. He drank,

used drugs.

Berke has never

felt comfortable around men -- he was repelled by the

angry, macho, emotionless male stereotype. He isn't

attracted sexually to men either and says he has never

had sex with one.

In 2003, at age

39, he became Michelle.

He spent about

$80,000, maxing out his credit cards on surgery and

provocative women's clothes. He got a nose job, a brow lift,

and fat injections in his cheeks. His primary care

physician gave him hormones, and after a year he got

breast implants.

Michael kept his

penis; that surgery cost too much, and he still

identified himself as a heterosexual. (He's had

relationships with women and says he's still hoping to

meet one with whom he could spend his life.)

The

transformation was easy, a dream. He had few friends as

Michael and no steady job, so there was no awkward

explanation to coworkers.

Michelle loved

pretty things. She made friends easily and was a great

dancer; Michael would have never stepped on the dance floor.

Michelle talked

to her mom and sister for the first time in years. She

even flew to Cincinnati one Thanksgiving holiday and met her

niece and nephew for the first time. She went to

Narcotics Anonymous meetings for women and

''completely emotionally understood and identified with

their feelings.''

But even as

Michelle, the same old problems crept in.

''I was still the

same person inside. Michelle was just the exterior,''

Michael says.

She was depressed

and suicidal and prone to cutting herself. She threw up

her food trying to fit into her jeans, eventually dropping

from a size 12 to a 7. She struggled with drugs and

alcohol, just like Michael.

By 2005, Michelle

had tried everything else, ''so why not God?'' A friend

invited her to church.

*

* *

An evangelical

church with about 20,000 members -- one of the largest in

the state -- Calvary Chapel has a local reputation for

embracing gay parishoners. Its several gay and

transgender participants are not allowed to serve in

church leadership but are welcome to attend services where a

Bible-based message teaches sex is supposed to be reserved

for marriage between a man and woman.

Many evangelical

churches have evolved from fire and brimstone preaching

against gay and transgender people and now view those

members as having a psychological illness much like

depression -- something that must be dealt with

spiritually, says Melissa Wilcox, assistant professor of

religion and director of gender studies at Whitman College

in Walla Walla, Wash. Of course, the psychological

establishment has long disputed the notion that

homosexuality is a mental illness.

''The churches

that only see it as sin would not be welcoming to someone

like Michael at all,'' said Wilcox, author of Coming Out

in Christianity: Religion, Identity, and

Community. ''It's a way of living out their beliefs of

you love the sinner and you hate the sin. Since the

early '90s that's increasingly been the direction that

a lot of evangelicals have moved in ... because it

offers hope.''

Michelle loved

the upbeat music and the feel-good sermons.

Everybody seemed

so nice. They put her in a special women's Bible study

group, so Michelle would feel more comfortable. Her new

friends showed her videos about a gay man who became a

woman and then a man again, and married a woman with

whom he had children and lived happily.

You can have that

too, they said.

They said

''you'll be able to meet a wonderful woman and get married,

and that's what pulled at my heartstrings because I

really wanted that,'' Michael recalls. ''I thought I

was doing the right thing.''

By the time

Michelle first met Calvary Chapel pastor Bob Coy, she was

self-conscious about the D-size breasts she had had for over

a year and had started wearing baggy men's shirts to

hide them.

During the altar

call one Sunday, Berke found God. And several weeks

later, Michelle told church leaders she wanted to become a

man again.

''This is a man

with tears in his eyes who asked for help,'' says Coy, a

bearded, charismatic leader whose own story is one of

redemption from drinking, drug-taking, and the

excesses of life in the music industry.

Church leaders

spent weeks counseling Michelle. They brought her to their

thrift store, allowed her to pick out a new wardrobe of

men's clothes for free, says Craig Huston, a church

employee. And they arranged for a plastic surgeon, a

member of the church, to remove her breast implants at

no charge.

When do you want

to have the surgery? the doctor asked.

''Tomorrow,''

Michelle joked.

The doctor

penciled her in for 10 a.m. And just like that, Michelle was

gone, Michael says sadly.

*

* *

The regrets came

quickly.

Michael turned to

the Bible and other theological books but found more

questions. He questioned the validity of the resurrection

and the belief that there was only one true religion.

Three months

later he stopped going to church and started partying again.

He downed handfuls of pills and chased them with vodka in

what he said was a suicide attempt.

That's when he

rode his Harley back to the church and confronted the

leadership. Michael, now 43, says he was cajoled into the

decision to become a man again; he was the church's

''pet project.''

Coy says the

church had no agenda with Michael. He asked. It helped.

''I'm aware of

the legal ramifications and the spiritual ramifications if

someone was forced to do anything,'' Coy says. ''Anything

that we have helped Michael with, he's asked for. The

hours of time that different leaders have spent

pouring into his life ...''

Like the time

Michael bought a motorcycle and lit it on fire. The church

sent the bike ministry over to help. One of the guys even

lent Michael his bike, says Huston.

''He goes in

these waves where he goes from one emotional extreme to the

other,'' Huston says.

He says Michael

was the one who asked for the surgery and pressed to have

it done quickly.

''We encouraged

him, but he initiated it,'' Huston says.

*

* *

Looking at

Michael today, it's hard to tell Michelle ever existed or

that he still longs for her.

His head is

shaved. There is a faint, rainbow-shaped scar on his

forehead where he had the brow lift.

His red goatee is

long and gnarly. He favors jeans, muscle tees, and

black combat boots. His mannerisms aren't feminine; his

voice is low, his gaze direct.

He attends a

couple of Narcotics Anonymous meetings a day, just to get

by.

Sitting in the

home his estranged father bought him, Michael listens to

opera and chain-smokes Camel Reds. He talks about Michelle's

favorite strappy heels and pink lingerie like they are

old friends. She loved to shop and nearly bankrupted

Michael, he says. Her clothes went to her best friend,

Rachel; it's too painful to keep her finery around now.

The only

reminders are in Michael's bathroom -- a hot pink rug,

butterfly towels, a vase of flowers, and a white

vanity mirror where Michelle did her makeup.

Realistically, he

knows he can't become Michelle again.

''If I do it

again people are going to think I'm even more unstable,'' he

says. His mom and sister stopped talking to him, he says,

when he switched back to Michael.

He talks about

going back to college to study psychology or maybe writing

books about his life. He doesn't work, relying on money from

his father and disability checks because of a knee

injury.

He vacillates

moment to moment, between depression and hope.

''I still

struggle just living on a daily basis,'' he says.

Then, minutes

later: ''Maybe I just need to meet the right woman and have

a relationship. Really, I'm without any sense of direction

right now.'' (AP)

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes