All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

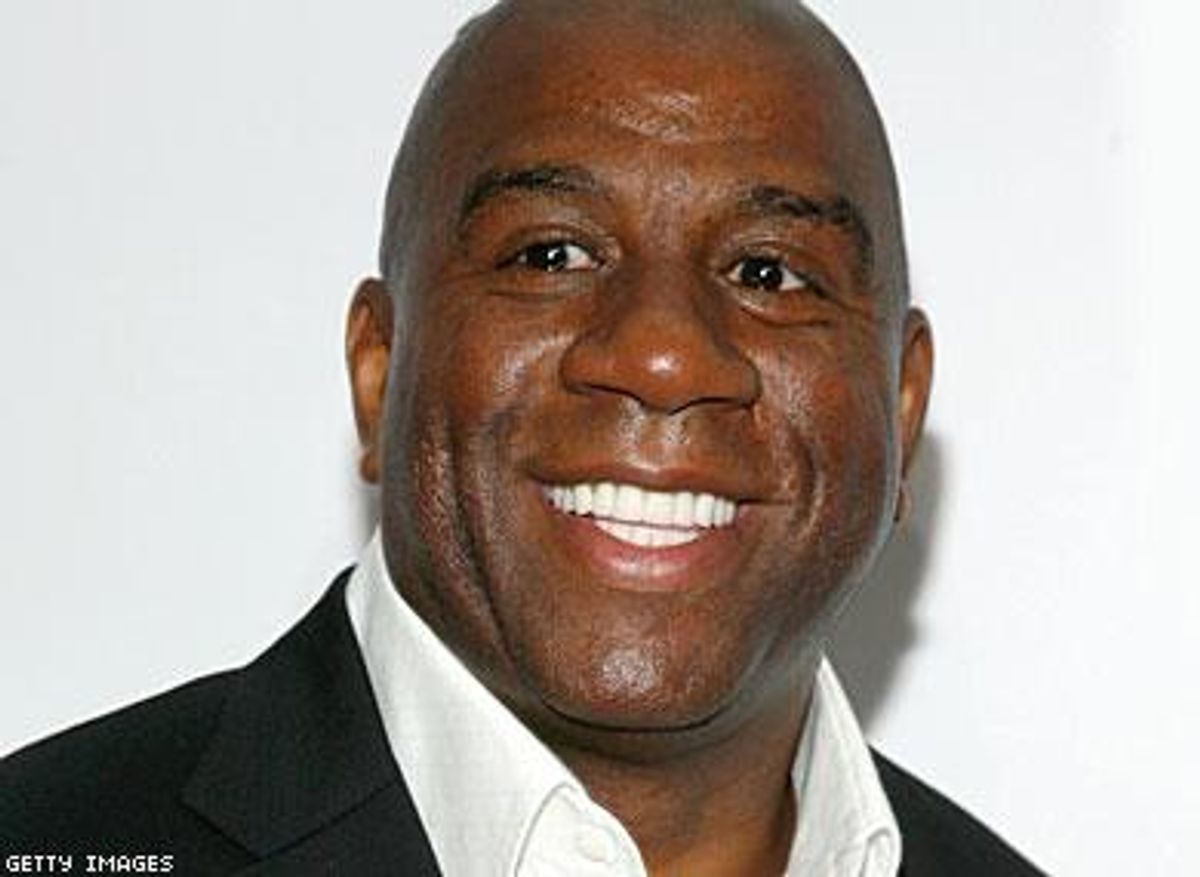

Twenty years ago this week, basketball icon Earvin "Magic" Johnson announced he was HIV-positive. The news shocked the world, especially for those who thought HIV was a disease reserved for gay men or the island of Haiti. For me, a 14-year-old who fearfully associated HIV with gays and death, Magic Johnson's disclosure was one of the key moments in my thought process about HIV and AIDS.

I first heard the term AIDS in elementary school. As part of health education, I saw a short film about a young black man (it was implied that he was not hetero) in New York City who was suffering from a mysterious disease.

The imagery was confusing and tragic, and it sparked a fear in me. I knew I was gay and wondered if the fate of this young man in the short film would inevitably be mine. At the film's end the man collapsed, with lesions all over his body. My elementary-school mind was left with an eerie question: Is this what happens to all men who have sex with men?

I didn't get an HIV test until I was 20 years old. Although I was constantly around people who were advocates of safe sex and knowing your status, I, like many others, was terrified. I was afraid of the outcome and the wait. Even in the late '90s you had to wait a full week for test results.

After landing a random job in Philadelphia, I was blessed with health insurance. Being excited to have a job that included benefits, I pulled out the phone book and ignorantly searched for the closest doctor in my area.

The moment I saw the doctor I was uncomfortable. He was much older, stiff, and barely looked me in the eye. He appeared to be comfortable with me until he peeked at my chart, where had I marked my sexual partners as male. After he glanced at me, then glanced back at the chart, I knew he had conjured up a pot of assumptions.

Ignoring my intuition, I casually explained that my main reason for the appointment was that I had acne and wanted a prescription for Differin Gel. Barely responding, he blinded me with a massive surgery lamp, inspecting my face. As he squinted through huge glasses he let out, "Those are the kind of bumps people who have AIDS get -- we better draw blood!"

My mouth dried up, I lost feeling in my fingertips, and I felt dizzy. Did he just diagnose me with AIDS? Although he didn't exactly say I was positive, because I was a young man who had never been tested and had a fear of the disease, "AIDS" was all I heard. I should've known the doctor was wildly ignorant, but in that moment I was too shocked to think normally.

Sensing my fear, the nurse hastily sat me down and asked what was wrong. I told her, "I'm scared." She unsympathetically asked, "You're not going to pass out, are you?"

I ignored her as she prepared to draw blood. She snapped, "Well, if you didn't do anything, you don't have anything to worry about!" She rammed the needle into my arm, where I later developed a bruise.

During the hellish weeklong wait, I saw a dermatologist (got my acne cleared up) and went to Planned Parenthood for another test. When I spoke to my friends they all assured me I was fine and gave the example of Magic Johnson. "Even if you are, look at Magic Johnson!" At first I was annoyed by the analogy. The basketball icon was rich and privileged -- how could his story help me? But eventually the thought of Magic calmed my nerves. At that point I didn't know anyone who was open about being HIV-positive. Magic Johnson was the sole example, especially from a black man.

I got my results back from the awful first doctor via phone. He flatly said, "You're fine." I breathed for what felt like the first time in a week.

Nonetheless, I told him, "You are the most unprofessional doctor I have ever had. How dare you tell me I had AIDS because I had acne? I hope you are never on the other side of the table!" I hung up as he repeatedly yelled, "Wait a minute!" Of course, my other results were also negative. I had never even had unsafe sex, but the fear got the best of me.

HIV is not only a physical disease, but an emotional disease. Many of us are HIV-positive emotionally. We live in fear of the conspiracies, injustices, and lack of information. We operate so carefully that we are not truly living. I have always admired Magic Johnson's candor about his diagnosis. Although he is rich and privileged, he is an example of living in truth, especially 20 years ago, when your truth was often criminalized.

For many of us, the fear still whispers. We have been socialized to have a terror of HIV. For many LGBT people, HIV is a part of our daily lives, whether we are positive or negative.

Clay Cane is a journalist and host of the radio show Clay Cane Live on WWRL 1600 AM. Follow Clay on Twitter attwitter.com/claycane.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

Meet all 37 of the queer women in this season's WNBA

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

Trending stories from our video partner Advocate Channel.

For more videos and shows go to advocatechannel.com.