"[Howard and I] didn't think anything of it," he says now.

Bringing a same-sex date to prom still turns heads, but it's swiftly becoming a nonstory. To most Gen X gays, even many millennials, being allowed the rituals of straight teendom with a same-sex partner was inconceivable in the '90s and 2000s. After graduation, many gays escaped to college or big cities where they could live out the adolescence they were denied. If they didn't have the resources to leave their stifling hometowns, many stayed in the closet until finding an accepting self-made family. But as the world changed, as "don't ask, don't tell" fell away, as same-sex marriage became more than a Massachusetts anomaly, and now, with activists hoping the Supreme Court will bring the number of states with marriage equality from 37 to 50, so have the rites and monolithic experiences of gay life.

"I remember canvassing for the right to marry at a young age," Ferrusi says, admitting his neighbors didn't need much convincing. "My community and classmates overwhelmingly supported marriage equality."

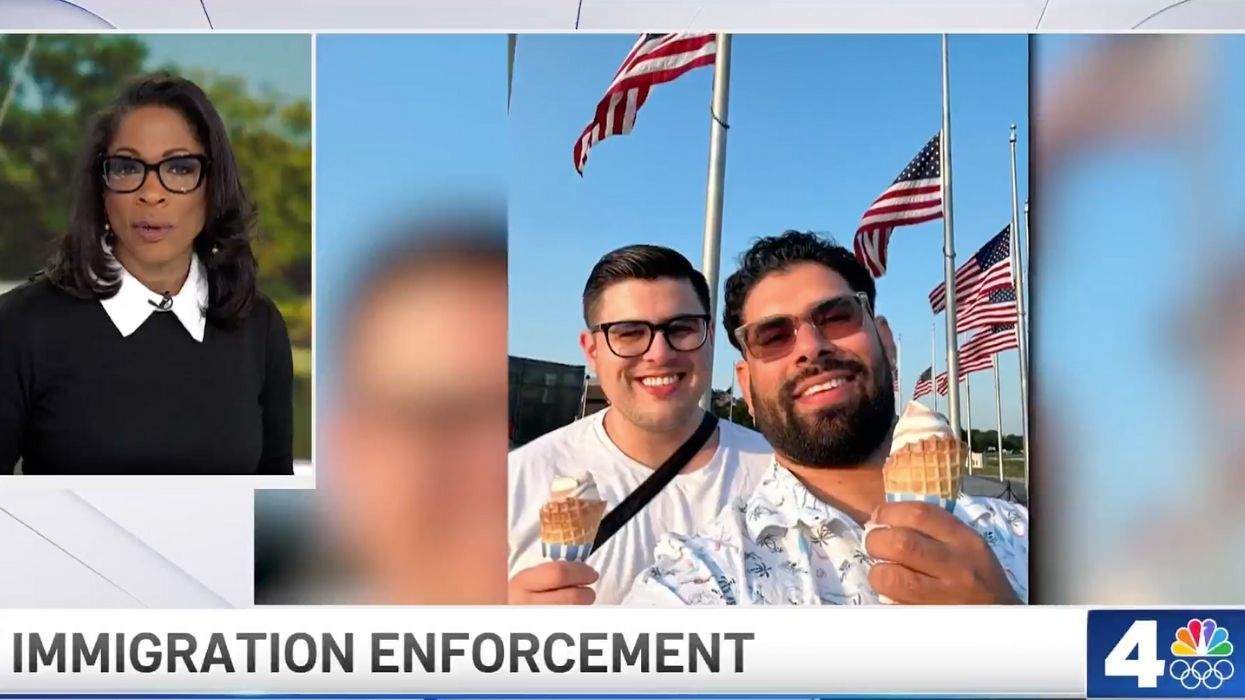

Ferrusi knew that by the time he was old enough to marry, he'd be able to (New York legalized same-sex marriage a year after he graduated). Having the option to wed is unquestionably good, but did Ferrusi lose something with all that's been gained? It sounds contrarian to question progress, but with institutionalized antigay discrimination receding into the past, the bonds that connected so many disparate LGBT people through shared experience seem to be untethering as well.

For anyone old enough to remember the marches on Washington, it's bittersweet to think one may never happen again -- even if they may no longer be necessary. While ACT UP remains, the urgency of its work is long gone now that HIV is a treatable disease. And gay ghettos, now increasingly the domain of straights, were often stifling, but they offered community.

We're not just staking out lives on the coasts but making our presence known in Kentucky and Utah and the Alaskan wilderness. Living childless existences with "roommates" is no longer the only future possible. With courts striking down remaining adoption bans, more gays are raising children. Just like we try to convince straight and cisgender voters who (still) get to decide whether to take away our rights, we're normal.

Back before we could even consider marriage, some gays and lesbians dismissed it as an outdated institution that often led to the subjugation of half of the pairing (namely, the female half). Now 60 percent of gay and lesbian people are married or want to be. Single life has long defined the image of gays to straights and to themselves. Especially for gay men, clubs and bars were a way to not only hook up but congregate and commiserate. Now, with social media and integrated nightlife, legendary gay clubs and bars like New York's Splash have shuttered. Los Angeles and San Francisco can't even claim one lesbian bar between them.

Dave Cooley, owner of West Hollywood's the Abbey, arguably the most famous gay bar in the world, says the role of gay gathering places changed as LGBT acceptance grew.

"Gay bars used to be a secret place that you only wanted other gays to know about," he says. "Being gay used to be a secret. Many of them also used to be places for sex. It wasn't that long ago that 'back rooms' were common. Now most of us live our lives in the open."

Cooley's bar has been criticized for being overrun by straight patrons, something unimaginable for a gay establishment 20 years ago. Some see that as a sign of progress, others a harbinger of assimilation and erasure. Cooley, unsurprisingly, doesn't take such a fatalistic view.

"There will always be gay bars, country bars, and sports bars," he says, "but part of living life in the open means that no matter who you are, you should be accepted at all of them." Because of dating apps, "bars and nightclubs are no longer just a place to meet people, they're a place to go with your friends and be entertained."

Of course, not all LGBT people see nightlife as a central part of gay culture. Few can actually agree on what gay culture is, exactly. Lesbians generally don't have as much of a fondness for divas like Madonna and Beyonce, while most gay men aren't familiar with the Dinah Shore Weekend or Tipping the Velvet.

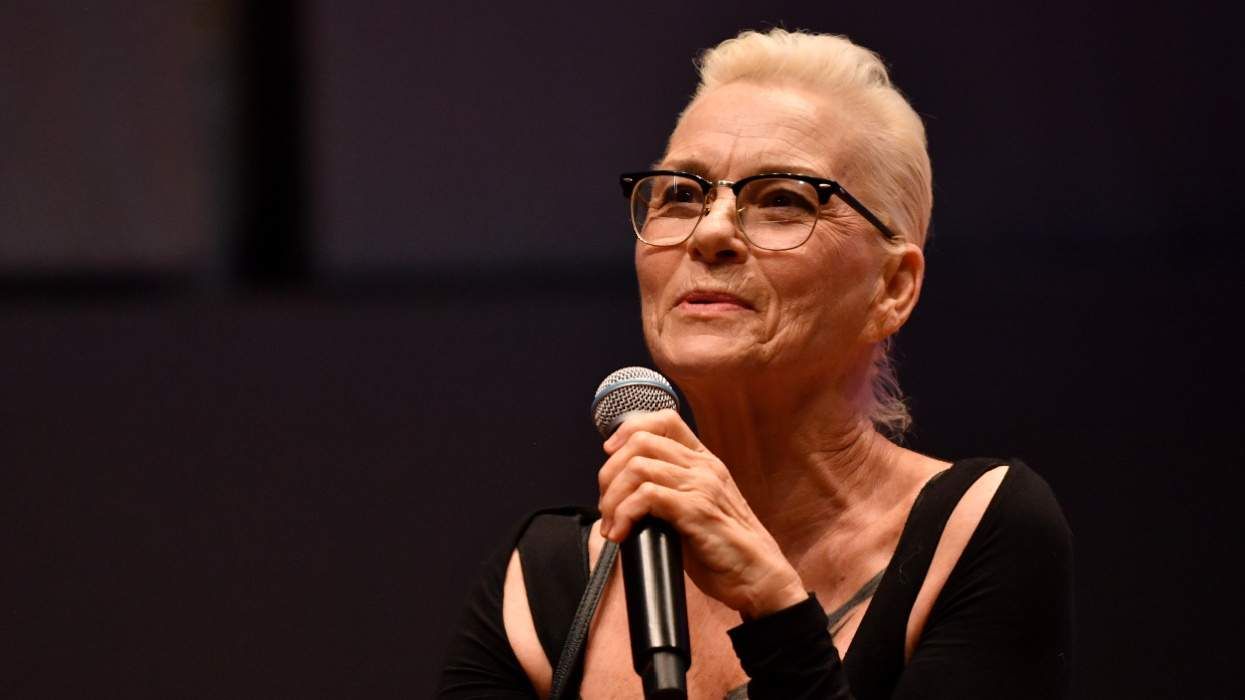

"From the first 'homophile' organization in the 1950s, to the present, there have been internecine battles about what gay and lesbian 'culture and identity' ought to look like," says LGBT scholar Lillian Faderman, who's authored books such as To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America and Gay L.A. "But the fact is, there's never been a single gay and lesbian 'culture and identity.' We're as varied as is the heterosexual population -- which makes sense, since, like straight people, we represent different generations, geographies, races, ethnicities, classes, and genders."

Tracy Baim, the publisher of Chicago's Windy City Times, echoes Faderman's statements, saying, "LGBT culture has always been very loosely connected." She does believe that the height of the AIDS battle in the 1980s and early '90s brought gay men, lesbians, and transgender people together, regardless of race and economic status. Marriage equality remains a big-tent issue that brings LGBT people together, though not with the same urgency as HIV and AIDS once did. When marriage equality becomes a done deal, "it will create a vacuum that must be filled with continued vigilance on other LGBT issues, and widening the movement, not narrowing it," she says.

The fight for marriage has been criticized as largely a concern of wealthy, white, cisgender gay men. Baim says those with money and power cannot ignore the staggering discrimination that still exists for many LGBT people, especially those outside of privileged bubbles. That's something the owners of the Out NYC Hotel may have forgotten; they recently hosted a reception for right-wing presidential candidate Ted Cruz, who is not just anti-LGBT but whose policies do no favors for immigrants and the working and middle classes.

"As we receive more acceptance from society and our own families, that does fill up our calendars with more obligations such as baby showers and birthdays, weddings and anniversaries," Baim says. "We must remember that there are still reasons to come together as the entire LGBT rainbow, to make sure there is a safety net for our most vulnerable, including our youth, seniors, the transgender community, and those living in poverty."

If those concerns are not addressed, "there is a great risk that assimilation will come at the expense of building community for those who do need it," Baim says.

Formidable challenges to equality remain, and not just government-sanctioned bigotry like religious exemption laws and legalized employment and housing discrimination. Even if a slight majority of Americans supports marriage equality, homophobia and transphobia are a daily part of every LGBT person's life -- it follows gay men and lesbians when they hold hands in the street, bisexual people when they're dismissed by the media, and transgender men and women when they try to use the bathroom. All of these problems are connected, though they can seem disparate to each subgroup.

"What's always brought us together best is an enemy," Faderman says, "like Anita Bryant in the 1970s. Sociologist Eric Hoffer got it right when he observed that 'a movement can exist without a God, but no movement can exist without a devil.' Homophobia won't magically disappear if the Supreme Court decides that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry -- there'll be plenty of other 'devils' to 'bring us together as a minority and help us identify with each other.'"

Necessary But Dangerous: If the Supreme Court rules in our favor, not all of the effects will be positive. This is the fourth entry in The Advocate's special series that explores those possibilities. (Read parts 1, 2, and 3)

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.