This story is part of History is Queer, an Advocate series examining key LGBTQ+ moments, events, and people in history and their ongoing impact. Is there a piece of LGBTQ+ history we should write about? Email us at history@advocate.com.

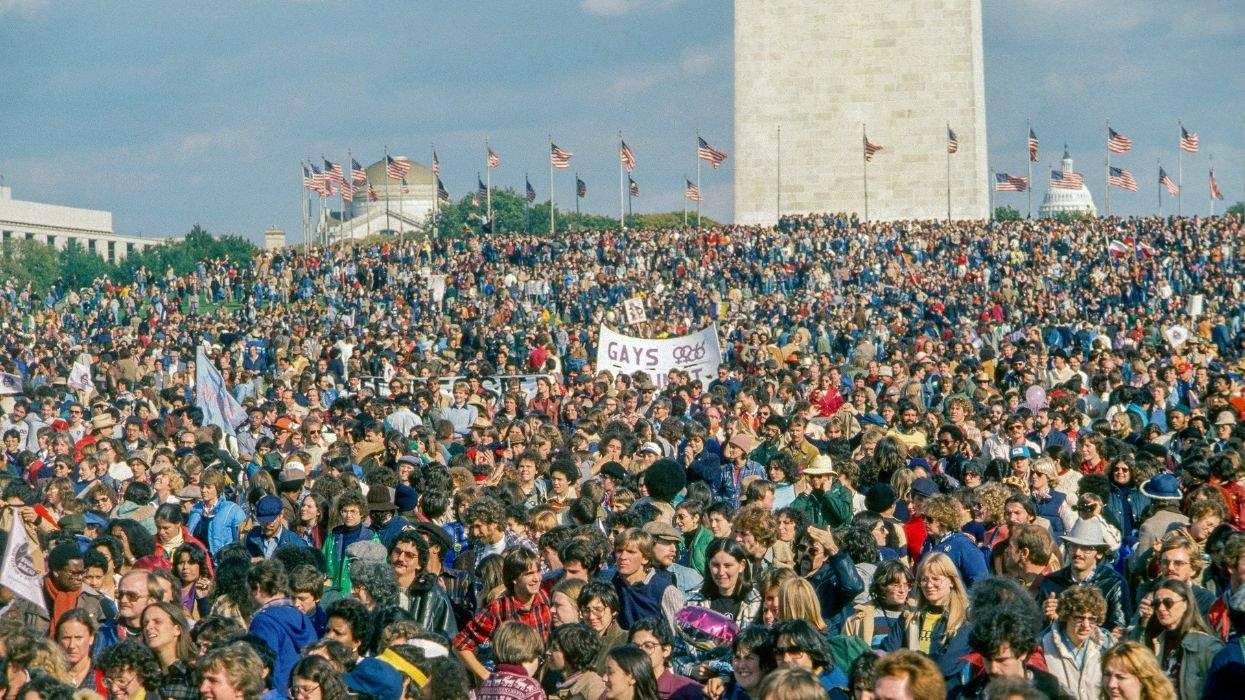

The 1970s was a significant decade for the LGBTQ+ movement. Building on the Stonewall uprising of 1969, new organizations were formed, such as the National Gay Task Force (later the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and now the National LGBTQ Task Force), PFLAG, and Lambda Legal. The decade’s work culminated in 1979 with the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, attended by an estimated 125,000 people.

The march had been long in the planning, and one who advocated for it did not live to see it — groundbreaking gay politician Harvey Milk. Here’s a look at the march, how it came to be, and what it accomplished.

The beginnings

“The earliest paper trail dates the organizing back to a meeting held during Thanksgiving weekend in 1973 by the National Gay Mobilizing Committee in the student union at the University of Illinois’ Urbana-Champaign campus,” Amin Ghaziani wrote in the Gay & Lesbian Review in 2005. Leading the meeting, Jeff Graubart, said one of the march’s purposes would be “to gain solidarity for the gay movement in the country, which … is now isolated and fragmented.” But no infrastructure for the march emerged from the meeting.

Then in October 1978, a Minneapolis-based group, the Committee for the March on Washington, began discussing such an event. “Unfortunately, a little over two weeks before a scheduled weekend meeting of lesbian and gay leaders from across the country, the Minneapolis group dissolved itself after deciding that serious internal disputes over racism and classism in the organizing process would keep it from effectively planning the march,” Ghaziani wrote.

Enter Harvey Milk.

In 1977, Milk had been elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the metropolis’s version of a city council. He was the first out gay elected official in California. After the Minneapolis group fell apart, he decided to assume responsibility for planning the march. But he was assassinated along with Mayor George Moscone on November 27, 1978, by Dan White, a former member of the Board of Supervisors.

Related: Who was Harvey Milk?

Two of the march organizers, Steve Ault and Joyce Hunter, felt Milk’s death gave them all the more reason to march. “This project must be carried out as a tribute to Harvey Milk and to the countless others who have suffered and perished at the hands of bigots,” they wrote to activists around the U.S., as quoted by Ghaziani. “We must fulfill Harvey’s dream for those who are still alive and for those yet unborn who shall love a person of their own sex.” There were soon calls for the march from all over the country. Organizers chose 1979 as the date because it marked the 10th anniversary of Stonewall.

Other organizers included lesbian comedian Robin Tyler and the Rev. Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church. “They were both powerful figures in the movement at the time,” The Advocate noted in 2017. “Tyler was known for producing events and readily pushing people, especially gay men, out of her way to get things done — her way.”

Also involved was Phyllis Frye, a lawyer often called the grandmother of the transgender rights movement. “Her trans advocacy would give birth to a movement, and she used the march organizing as a means of [achieving] that,” fellow organizer Ray Hill told The Advocate in 2022. “The state of our collective movement in 1979 was one of uneven development of its component parts. The trans movement did not exist, except for Phyllis’s advocacy.”

The march ended up reflecting the diversity of the community, even though no one used the term LGBTQ+ in 1979. There were trans and bisexual people as well as lesbians and gays, and a sizable presence of people of color.

The day

The march “had five core demands — comprehensive civil rights protections, the repeal of discriminatory laws, equal parenting rights, freedom from workplace discrimination, and an end to anti-LGBTQ+ immigration policies,” Ohio-based Stonewall Columbus notes on its website. These “were bold and radical at the time,” the group adds. They remain relevant today, as there are still laws that discriminate against LGBTQ+ people, especially trans people, and the federal government has never enacted an LGBTQ-inclusive civil rights law. The Employment Non-Discrimination Act never passed, nor has its successor, the Equality Act.

March attendees gathered at the U.S. Capitol, walked up Pennsylvania Avenue past the White House, and then held a rally on the National Mall.

One of the speakers at the rally was Charles Law, a Black gay man from Houston who was a university archivist and a founding member of the Houston Committee, a Black gay men’s professional group. He called for “Integration, and not assimilation,” according to a profile on the National Park Service website. Gays and lesbians needn’t be exactly like heterosexuals in order to have equal rights, he said. “I am afraid that we will find that those gay people who do not come across as being offensively gay, as militantly gay, obviously gay, adamantly gay, or admittedly gay will be the ones to reap the benefits … and the real sissies and the butch women of this country will still have to live in gay ghettos and not have achieved the true import of this movement,” he said.

The speakers also included renowned poet Audre Lorde, who called for an intersectional movement long before that term was popular. “We are saying to the world that the struggle of lesbians and gay men is a real and particular and inseparable part of the struggle of all oppressed people within this country,” she said. “I am proud to raise my voice here this day as a Black lesbian feminist committed to struggle for a world where all our children can grow free from the diseases of racism, of sexism, of classism, of homophobia, for those oppressions are inseparable.”

Another famed poet, Allen Ginsberg, read the poem “Song” from his book Howl on the rally stage. His partner, fellow poet Peter Orlovsky, read the poem “Someone Liked Me When I Was Twelve” from his book Clean Asshole Poems & Smiling Vegetable Songs.

Tyler brought her signature humor to the event. “Someone said that this gathering is about showing society that we are just as good as anybody else,” she said, according to a contemporary account in The Washington Post. “Well, I say because of the oppression we have endured, we are better.”

Richard Ashworth of PFLAG — then known as Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays — drew cheers and applause when he said, “We love our gay children,” the Post reported. “They are not being defiant or self-indulgent, just true to their nature,” he continued. “This is not a fad, but something established in infancy, perhaps before birth. They didn’t catch it. It isn’t a disease to be cured.”

- YouTube www.youtube.com

- YouTube www.youtube.com

There was some homophobic opposition to the event. “About 75 Protestant ministers and churchgoers met in the Science and Technology hearing room of the Rayburn House Office Building to pray that homosexuals would ‘repent,’” the Post noted. One of them was the infamous televangelist Jerry Falwell Sr. “God didn’t create Adam and Steve, but Adam and Eve,” he said.

“Homosexuality, like theft, like drug addiction, begins with choosing to disobey the laws of God,” he added. “I would not object to gay people having equal housing or employment opportunities. But I would object to them teaching in the classroom and to them holding any position of leadership.”

The equally infamous antigay crusader Anita Bryant didn’t go to Washington but sent a telegram saying she was praying “for those misguided individuals marching in Washington today who seek to flaunt their immoral lifestyle.”

Related: Why did a gay man throw a pie in Anita Bryant's face, and who was he?

There were just a few hecklers along the march route, according to the Post article. One of them held a sign saying, “Repent or perish — II Peter, 2:12.” A member of the L.A. Gay Freedom Band responded by yelling, “The lord is my shepherd. And he knows I’m gay.”

The aftermath

As noted, many of the demands of the 1979 march remain unmet. But the movement had been energized and to some degree unified. “Here we are knitting a whole new identity out of the once-scattered threads of our community,” The Advocate wrote of the event.

That energy and unity would be much needed in the next couple of decades, as AIDS devastated gay men and trans women. There were national LGBTQ+ marches again in 1987, 1993, 2000, and 2009, then multiple Trans Visibility Marches.

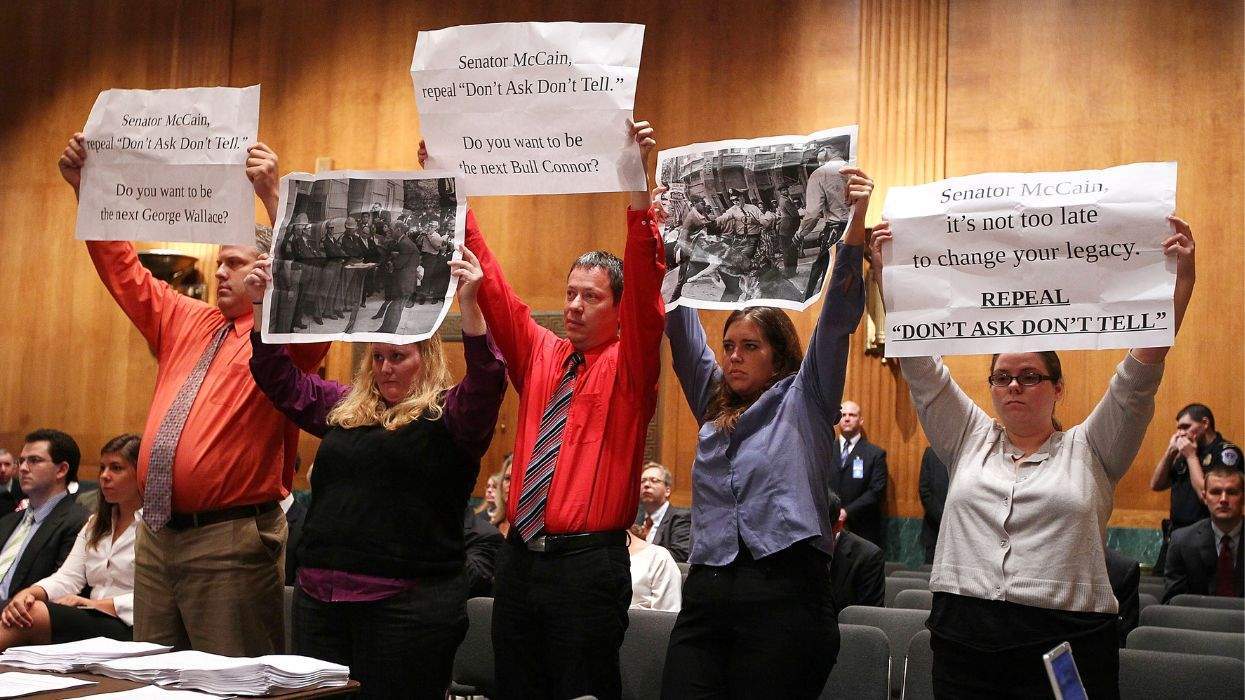

Over those years, the community has seen progress and setbacks — “don’t ask, don’t tell” and its repeal; an inclusive federal hate-crimes law; the Defense of Marriage Act, its invalidation, and then national marriage equality; the LGBTQ-supportive policies of Presidents Obama and Biden, then the hostility, especially to trans people, of Donald Trump.

But the 1979 march “was a declaration that LGBTQ+ people would not be invisible or silent,” Stonewall Columbus notes, and there was no going back. “For many who marched, this was their first time stepping out of the shadows to publicly declare their identity. The courage required to do so in 1979, when public displays of LGBTQ+ pride were met with hostility, is a reminder of the resilience and bravery that has always fueled our movement.”

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.