This story is part of History is Queer, an Advocate series examining key LGBTQ+ moments, events, and people in history and their ongoing impact. Is there a piece of LGBTQ+ history we should write about? Email us at history@advocate.com.

In 2026, the words “don’t ask, don’t tell” live in infamy, reminders of a discriminatory policy that has rightly been consigned to the dustbin of history. But when the policy was enacted, it was actually supposed to make life better for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people serving in the military. Here's how the policy came to be, how it affected service members, and how it was repealed.

Bill Clinton makes a promise

Democrat Bill Clinton won the presidency in 1992 with a mix of liberal and conservative stances. One of the former was his promise to lift the ban on military service by LGB people (transgender service members were banned under a different policy, primarily on medical grounds, and there was little public acknowledgment or understanding of trans people at the time).

Since the nation’s founding, the U.S. military had a variety of policies designed to keep LGB people out. When “sodomy,” generally defined as any nonprocreative sex, was a crime, it was a reason to discharge military members. The first one known to be kicked out for sodomy was one of George Washington’s soldiers in the American Revolution, Lt. Gotthold Frederick Enslin, in 1778, according to the U.S. Naval Institute.

Regulations against sodomy continued in various forms over the years, and there was even a short-lived sting operation in 1919 to entrap sailors seeking gay sex. Then in 1921 the Army issued standards saying “sexual perversion” would disqualify men from military service. More antigay policies were issued during World War II and in the succeeding decades.

That didn’t mean LGB people didn’t serve. The military often looked the other way when it needed troops, and of course many served from the closet. One of the latter was Air Force Tech. Sgt. Leonard Matlovich, a gay man who received medals in the Vietnam War, then came out on the cover of Time magazine in 1975 and challenged the military’s exclusion of LGB people. He lost his suit, and his coming-out got him discharged, although a settlement made the discharge an honorable one, unlike those received by many. For instance, Harvey Milk received an “other than honorable” discharge from the Navy in the 1950s for being gay. Decades later, other service members continued to challenge the ban, including Army Staff Sgt. Miriam Ben-Shalom and Col. Grethe Cammermeyer.

The ban was strengthened in 1981, when the Department of Defense issued a directive stating that “homosexuality is incompatible with military service” and that any member who has “engaged in, has attempted to engage in, or has solicited another to engage in a homosexual act” would be discharged, In the 1980s alone, the armed forces discharged about 17,000 members for homosexuality.

But opposition is strong

Enter Clinton, who tried to make good on his promise early in his presidency. But his plan met powerful opposition, including from fellow Democrats, who weren’t universally gay-friendly at the time. Sam Nunn, the Georgia Democrat who chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee, was staunchly against lifting the ban. Gen. Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wanted to keep the ban in place as well.

While they and others remained fairly civil, there was homophobic hysteria from some. The idea of gay men sharing barracks and bathrooms with straight men, or lesbians with straight women, was alarming to homophobes, just as the idea of trans women in women’s restrooms is shocking to right-wingers today. At the first Armed Services Committee hearing on lifting the ban, held in March 1993, some members wondered “whether the military would be legally obliged to provide separate housing and bathing facilities for homosexual and heterosexual soldiers,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama, who would switch from Democrat to Republican the following year, “asked whether disgruntled heterosexual soldiers would be able to sue the government for breach of contract if the ban is lifted,” the Times article noted. Idaho Republican Sen. Dirk Kempthorne wondered if straight service members could refuse to serve with gay troops on religious grounds.

But at that same hearing, Nunn suggested what would become the law of the land: “don’t ask, don’t tell.” “I see problems with every direction, from backwards to forward to standing still,” he told reporters after the hearing. “But I see less problem with that.” Clinton, meanwhile, had already agreed to the “don’t ask” component of the policy in a January meeting with the Joint Chiefs, so inductees would no longer be asked about their sexual orientation.

Both the Senate and House Armed Services Committees held hearings on the issue during the spring and summer of 1993, and it became clear that Clinton didn’t have the support to end anti-LGB discrimination in the military altogether. After consultation with a Military Working Group, he outlined “don’t ask, don’t tell” at the National Defense University on July 19, 1993. The same day, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin sent armed forces leaders a memo stating, “Sexual orientation is considered a personal and private matter, and homosexual orientation is not a bar to service entry or continued service unless manifested by homosexual conduct.”

That still didn’t satisfy opponents in Congress. A stricter vision of DADT was passed into law in late 1993. It “stipulated that known gay men and lesbians would pose an ‘unacceptable risk’ to military effectiveness and that the exposure of gay or lesbian sexual orientation, irrespective of other same-sex conduct, was enough to warrant investigation and separation,” notes the 2010 book Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy. The law went into effect in 1994.

LGB troops continue to suffer

Still, while LGB troops were expected to remain closeted, the military was not supposed to seek them out. The longer nickname of the law was “don’t ask, don’t tell, don’t harass, don’t pursue,” but some military officers continued to ask, harass, and pursue. And staying closeted, naturally, was a huge challenge.

“The problems encountered are endless,” a lesbian service member told The New York Times in 2010. “How does a young gay [noncommissioned officer] live with his partner when he is forced to live in the barracks because the Army does not recognize his marriage? How can a soldier receive emergency leave for a spouse who does not exist, according to the Army? How is it possible to incorporate your partner into family readiness groups while deployed?”

A Navy intelligence analyst emailed this toThe Advocate in 2007: “As I sit here and type this message, I am also working on a classified briefing concerning terrorists who we are helping to track down. How funny is it that I’m here trying to help inform people of bad guys who are trying to kill innocents of their own country as well as many Americans, but if I was found out to be gay I’d be yanked out of here so fast?”

More than 13,000 service members were discharged under “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Most of them received honorable discharges, which gave them access to full veterans’ benefits, but some received “other than honorable” or “less than honorable” discharges, something that could interfere with benefits. Most of these discharges were upgraded after DADT’s repeal.

New hope with Obama

When Barack Obama ran for president in 2008, he promised to repeal DADT. In the years since the policy was adopted, some who had backed it had expressed regrets (eventually including Clinton, Powell, and Nunn), and public support for it had dropped, especially after troops were sent to Afghanistan and Iraq in the early 2000s.

In his first week in office in January 2009, Obama met with Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Joint Chiefs Chairman Adm. Mike Mullen and told them he wanted to end DADT, the president toldThe Advocate the following year. In his 2010 State of the Union address, Obama pledged to work to repeal DADT that year.

However, he was waiting for the completion of a study by military leaders on the potential impact of the repeal. They eventually found that most service members were already serving alongside people they knew to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and there were no negative effects on unit cohesion, morale, or readiness.

Related: Don't Ask, Don't Tell... Don't Blow It

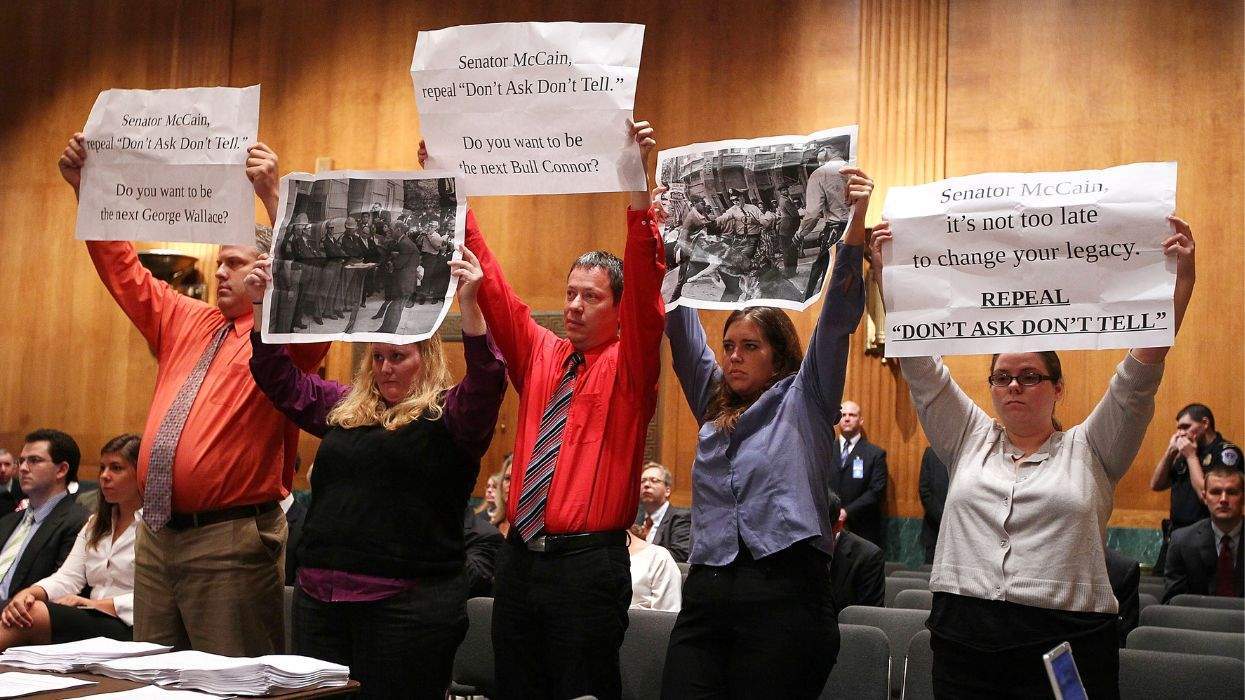

Still, the road to ending DADT was fraught with tough negotiations in the House and Senate, and outcry by military members and activists who said the process wasn't moving quickly enough; some notably protested by chaining themselves to the White House fence. Some Republicans in Congress wanted to maintain the policy, but repeal legislation ended up passing with bipartisan support. Obama’s vice president, Joe Biden, lobbied many members of Congress to support it.

The repeal happened in December 2010, with both the House and Senate passing a repeal bill and Obama signing it into law. “I am incredibly proud,” he told The Advocate shortly before the signing.

Then at the signing ceremony on December 22, he said, “We are not a nation that says, ‘don’t ask, don’t tell. We are a nation that says, ‘Out of many, we are one.’ We are a nation that welcomes the service of every patriot. We are a nation that believes that all men and women are created equal. Those are the ideals that generations have fought for. Those are the ideals that we uphold today. And now it is my honor to sign this bill into law.”

After that, the Defense Department had a window of time to implement the repeal consistent with standards of military readiness, and it took effect September 20, 2011.

The right thing to do

Years later, there’s wide agreement that repeal was the right thing to do. On the 10th anniversary of the signing, U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, then speaker of the House, issued this statement: “Ten years ago, our nation took bold action to end a fundamental injustice that had inflicted shame and distress on tens of thousands of brave, patriotic LGBTQ servicemembers. With the repeal of the hateful ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy, we strengthened our national security and reaffirmed the bedrock principle that those willing and able to serve be treated with dignity and respect, regardless of who they are or whom they love.”

She continued with a plea to pass the Equality Act (still not done) and to repeal Donald Trump’s first-term trans military ban. Biden did that when he became president in 2021, but Trump reinstated it when he returned to office last year.

Related: Pride in the Military, a Decade+ After 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'

Leon Panetta, who succeeded Gates as Defense secretary, had this to say in a 2021 Advocate interview: “When we put the repeal into effect, the reality was that the military carried it out in a way with little disruption. It immediately benefited our fighting capability.”

If only certain parties would realize that letting trans troops serve openly would be beneficial as well.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.