Some of history's most infamous spies weren't just living a double life professionally — they were also secretly LGBTQ+.

Though their achievements aren't always documented, queer people have always existed and made contributions in every field, and espionage is no exception. Several spies spanning back centuries were what we would now consider to be LGBTQ+, even if the terminology wasn't coined until recently.

Some were able to live openly — others found that the information they spent their lives protecting would be what brought their downfall. From the world wars and Red Scare to the fight for Irish independence, here are some queer spies worth knowing.

The following visual collection was curated by equalpride's digital photo editor, Nikki Aye.

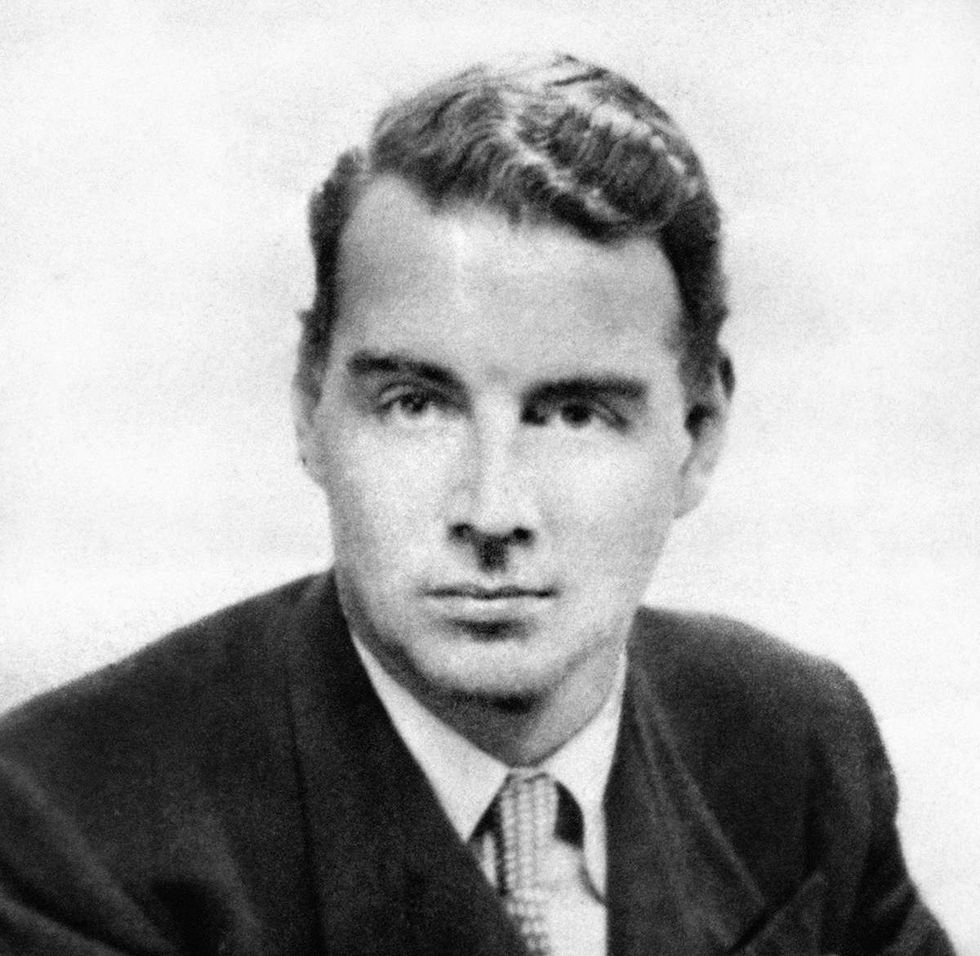

Guy Burgess (1911–1963)

Guy Burgess, 1951

PA Images Contributor via Getty Images

Guy Burgess was a member of the Cambridge Five, a group of double agents in the United Kingdom who gave information to the Soviet Union between the 1930s and 1950s, as documented by the MI5 files.

Burgess attended Trinity College, Cambridge, for his undergraduate degree, where he studied the works of Karl Marx and was moved to join the British Communist Party. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935 after dropping out of his graduate program and rebuked communism publicly in order to earn a position as an assistant to a conservative member of Parliament.

By the 1940s, Burgess had worked his way into a position with the Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known as MI6 (Military Intelligence, Section 6), the U.K.'s foreign intelligence service. There he passed along information to Soviet officials about the post-World War II futures of Germany and Poland, and any potential plans for war with the Soviet Union.

Burgess defected to the Soviet Union in 1951, where he stayed until his death from arteriosclerosis and acute liver failure in 1963.

Burgess was open about his attraction to men during his time at Cambridge and is believed to have been in a relationship with fellow Cambridge Five member Anthony Blunt. After defecting to the Soviet Union, Burgess was reportedly dismayed by the country's treatment of LGBTQ+ people but was able to find a partner, Tolya Chisekov, with whom he remained until his death.

Anthony Blunt (1907–1983)

Queen Elizabeth II discusses art exhibits with Sir Anthony Blunt during her visit to the Courtauld Institute of Art at London University, 1979

PA Images Contributor via Getty Images

Anthony Blunt was another member of the Cambridge Five, though accounts of how he joined he group vary. It's believed that Burgess recruited him in the mid-1930s, as they were both members of the Cambridge Apostles (also known as the Conversazione Society), a group of undergraduate men who shared an attraction to men and affinity for communism.

Blunt joined the British Army at the beginning of World War II in 1939 and was recruited in 1940 to MI5, the U.K.'s domestic intelligence service. Blunt used his position to send information to the Soviets, including encrypted messages and details about German spies in the Soviet Union.

Blunt's allies in the U.K. suspected him of having loyalties to the Soviets, with government agents questioning him more than 11 times in 1951. Even his Soviet allies suspected he was a triple agent based on the sheer amount of material he was handling.

Blunt would submit a full confession in 1964 in exchange for total immunity from prosecution and the condition that his story remain secret for 15 years. The British government kept its word, and in 1979 Blunt was stripped of his knighthood and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher revealed his espionage. He was labeled a traitor and rejected by the public until his death from a heart attack in 1983.

Interviews in the MI5 files explicitly confirm Blunt's sexuality, which he never denied during his life. He did deny ever having a relationship with Burgess, though he was said to be deeply shaken by Burgess's defection to the Soviet Union. Blunt met his known lover during his time at Cambridge, poet Julian Bell, son of painter Vanessa Bell.

Alfred Redl (1864–1913)

Alfred Redl, circa 1908

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Alfred Redl's life is regarded as one of the most infamous spy stories throughout history, as the Austro-Hungarian was a pioneer of espionage techniques prior to World War I.

Redl joined a military academy as a cadet at age 15 and steadily climbed the army ranks until he was appointed the head of the counterintelligence wing Evidenzbureau. During his tenure, he introduced several technological advancements to assist in investigations, such as early recording devices and fingerprinting databases.

Redl became a spy for the Russian Empire as early as 1902, when he was assigned to investigate an information leak it is believed that he himself was responsible for. He was regarded as Russia's leading spy, passing along critical information such as the locations and defenses of fortifications as well as Austria-Hungary's invasion plan for Serbia, which gave the nation time to prepare.

Redl left the counterintelligence service in 1912 and would be discovered as a spy the next year by the very man he trained to replace him. Investigators tracked suspicious mail with a large sum of money to Redl using the techniques he had implemented.

Redl was not executed formally but was left in a room with a loaded revolver, which he used to commit suicide in 1913. To this day it is not know why he became a spy, but it is believed that Russian agents learned of Redl's queer sexuality and used it to blackmail him into turning over information.

Roger Casement (1864–1916)

Roger Casement, circa 1900

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

Roger Casement was a human rights activist and Irish nationalist executed by the U.K. government for treason after dealing with the Germans during World War I.

Casement began his career as a human rights investigator for the African International Association, documenting human rights abuses in the Congo, Portugal, and Peru in the late 1800s. He retired from the British consular service in 1913 and began dedicating his time to anti-unionist efforts — Irish independence from England.

When World War I began in 1914, Casement traveled to the United States to meet with German diplomats and arrange weapons sales to Irish revolutionaries, hoping to spark the Irish to revolt and divert England's attention from the war. The weapons never reached Ireland, as the British intercepted the message and detained Casement upon his arrival back in the country.

Casement was tried for treason, during which journals claimed to be his — known as the Black Diaries — were used against him, detailing his paid sexual encounters with young men. The defense recommended submitting the journals as evidence, which would have caused the court to find Casement "guilty but insane" and ultimately spare his life.

Casement refused and was hanged in 1916 despite appeals from his friends and contemporaries, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and W.B. Yeats.

Chevalier d’Éon (1728–1810)

Caricature of Chevalier d’Éon, 1777

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Chevalier d’Éon was a French diplomat and likely transgender woman. While the term did not exist in her time, d’Éon was known for dressing in women's clothing and is even believed to have gone undercover disguised as a woman.

D’Éon began her career as a secretary and political writer and was eventually appointed as royal censor for history and literature in 1758. It was through her connections that d'Éon joined the network of spies called the Secret du Roi ("King's Secret") under King Louis XV.

D’Éon was appointed an interim ambassador while in London in 1763, befriending English nobility and passing along information — including about the king's plans to invade England — to fund her lavish lifestyle. Not wishing to give up her position when a new ambassador was chosen, d’Éon risked execution by disobeying an official order to return to France, and took shelter with the British.

After multiple failed attempts to kidnap her and bring her back to France, d’Éon threatened to publish information about the Secret if her name was not cleared. She published a first volume in 1764 containing much of her diplomatic correspondence, after which the French government sought to retrieve the papers still in her possession.

In exchange for the documents, d’Eon negotiated a deal that included some debt forgiveness, pension payments, and the agreement that the king would publicly recognize her as a woman. She remained in exile in London until she died in 1810 after becoming paralyzed from a fall.

Whittaker Chambers (1901–1961)

Whittaker Chambers testifies before the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1948

Bettmann Contributor/Getty Images

Whittaker Chambers was an American spy for the Russians who would later denounce communism and his past homosexual relationships.

Chambers, a graduate of Columbia University, joined the Communist Party in 1925, after which he wrote and edited for the New Masses and the Daily Worker. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence systems through the publications, under which he would work until 1937.

Chambers began to doubt his Russian overseers and fear for his safety after Joseph Stalin began the Great Purge in 1936. The show trials were meant to root out dissenters and led to the deaths of around 1 million people. Ignoring multiple orders to travel to Russia, Chambers left the party.

After speaking with a journalist, Chambers agreed to meet with the assistant secretary of State and pass along information about who was loyal to the Communist Party in exchange for immunity. One name that came up was lawyer and former government official Alger Hiss, who would later sue Chambers for defamation over the claims, prompting Chambers to release the evidence from his time as a spy.

Both Chambers and Hiss were suspected of being attracted to men. Hiss's stepson, Timothy Hobson, even accused Chambers of outing Hiss as a communist because he had unrequited romantic feelings for him. A letter from Chambers obtained by the FBI detailed his relations with other men in the 1930s, something Chambers would confirm in his memoir, Witness, but would also claim he stopped after renouncing communism.

Chambers would go on to become a writer for Time, and he died of a heart attack in 1961.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.