I want the youth to get curious about these phrases: “No carnal knowledge, no buggery, no gross indecency, no sodomy.”

These words, which many people don’t even understand in English, have prevented LGBTQ+ individuals from living their lives, getting married, changing their gender, and simply existing without fear of punishment. These words have caused divisions in families, ended friendships, and caused countless to be denied access to housing, medical, and employment opportunities. As an activist, I consider myself fortunate to have the chance to live and work within the queer community in Africa, as well as have the opportunity to visit other regions in the Pacific. However, what I find interesting is that across these two regions, there is a shared history of the laws that affect queer individuals in all of these contexts, which can be traced back to the impact of imperialism.

These harmful laws enacted during colonization were inherited by our lawmakers in their hurry to usher in independence. All these years later, they remain the loaded language used to intimidate and police queer identities. My politics surrounding the goal of queer liberation is the decolonization of these linguistic domains. I believe as long as these laws exist, then oppression lives on.

Anti-LGBTQ+ is deeply rooted in the language itself that impacts our very existence, an inheritance foreign to our lands. In the Pacific, for example, pre-colonial Pasifika families have long included, recognized, celebrated, and named queer people: māhū, vakasalewalewa, palopa, fa’afafine, akava’ine, fakafifine and similar names we belong to. Western language contextualizing queer identity cannot be limited to fit into these little boxes. The term MVPFAFF works to deconstruct the limitations placed on our identities.

These pre-colonial terms extend beyond some of the limitations of Western notions of the acronym LGBTQ+. For this reason, we need to return to a language that rehumanizes our existence.

Also rooted in these oppressive systems of punishment and incarceration are narratives that never existed. It’s important to remind ourselves that many of the systems, boxes, and biases used to punish or incarcerate queer individuals were introduced through colonial laws that also brought in police and prison systems. Pre-colonial Uganda is one of those filled with stories of our existence. The mudoko dako, for instance, was embraced by the Langi. It was accepted as something you were born as; to be a mudoko dako was a rare privilege and envied by many. They were not jailed, seen as perverse, or illegal. However, this perception was detrimentally enforced by the oppressive colonial laws, systems, biases, and phobias that worked to dehumanize indigenous people.

Colonial harm was so tangible in the past that it impacted identity and freedom of movement, expression, and knowledge. Its legacy today is less tangible but equally harmful, with the systems, laws, and institutions we ascribe to continue to perpetuate a narrative that violates indigenous and queer identity.

Homophobia, transphobia, and hate were introduced to our lands. Despite this, we queer individuals existed throughout time and will continue to exist.

We have to actively and intentionally stand for the rights of our humanity. Mobilize, protest, and reclaim words that re-empower the core of our unity.

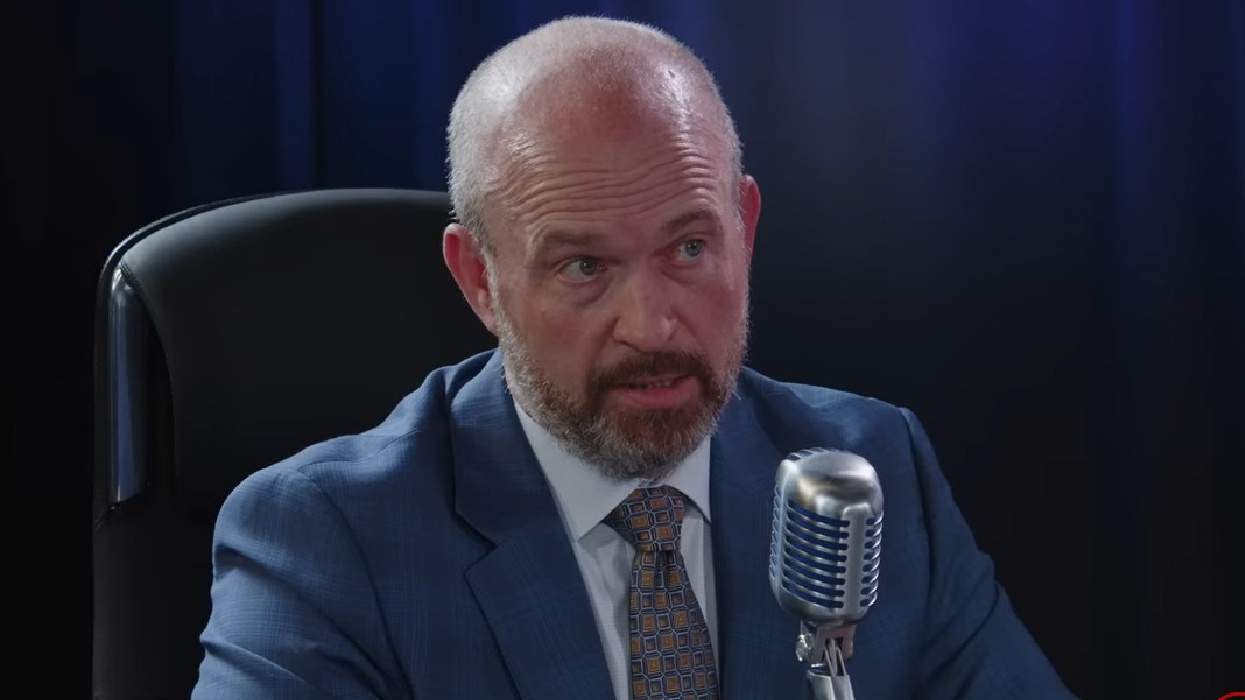

Trinah Kakyo is a Ugandan-based activist and founder of the Kakyoproject, a space for queer creatives.

Have an inspiring personal story to tell? Want to share an opinion on an issue? You can learn more by visiting advocate.com/submit.