After carving his own path far from the halls of power and the shadow of his famous father, gay Angolan fashion designer Coreon Du is once again being eclipsed by someone with whom he shares a name.

Du's sister, Isabel dos Santos, (known as "Africa's richest woman") made her fortune when she and her husband aquired valuable Angolan land, oil, diamonds, and telecoms assets for bargain prices as the former state holdings were privatized.

Last week, allegations surfaced that dos Santos had gained access to these lucrative deals through her (and Du's) father, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, when he served as president of Angola from 1979 to 2017.

Dos Santos, who currently lives in the United Kingdom and Portugal, is now reportedly under criminal investigation by Angola authorities, and her assets in the country have been frozen. She's since denied all allegations against her, citing a politically motivated "witch-hunt" by the current Angolan government.

Following reports about the alleged corruption, Du issued a statement to The Advocate:

"No one chooses the family they are born into, but everyone has a human right to dignity, their own individuality, and to privacy," Du said in the statement. "This is a right that I had never enjoyed since birth due to my genetic relationship with people who chose careers in politics or other high-profile positions. As proud as I am of my personal identity, I never chose to be a gay man of color who also happens to be genetically related to people in certain positions. My work has always been in the public eye and I have never held public office in Angola or anywhere else, nor have I ever held any political affiliation."

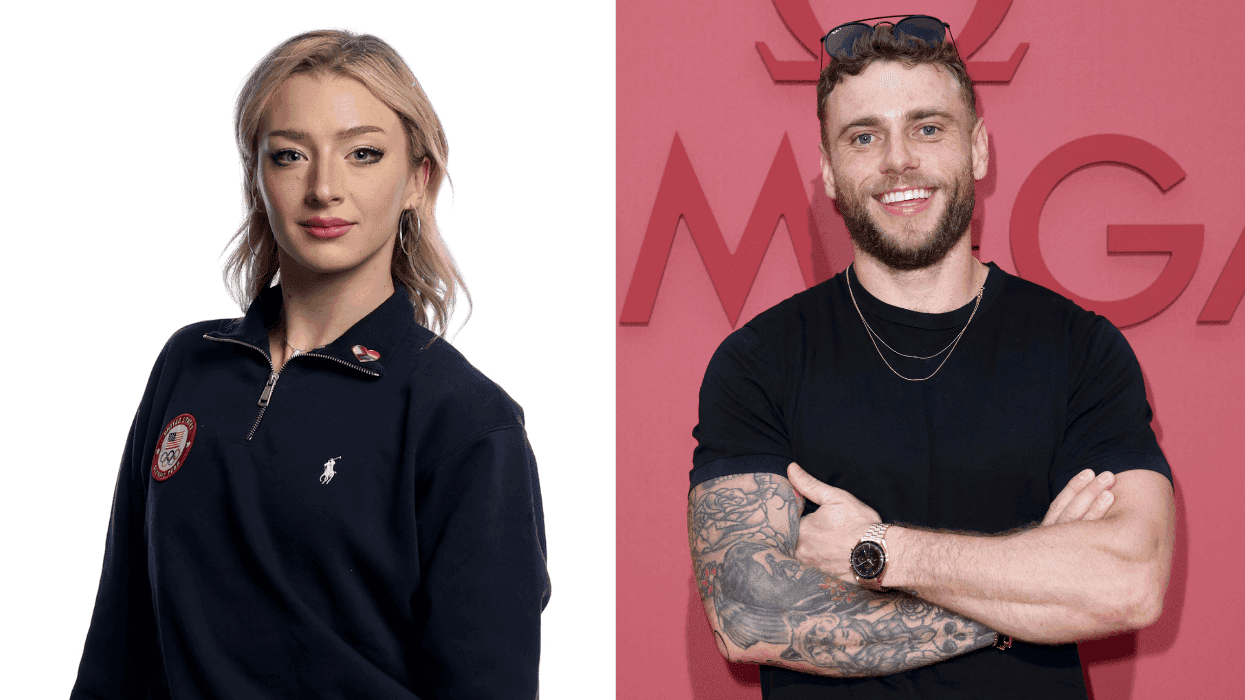

Pictured: Coreon Du. Photography by Joel Bessa

Du, christened Jose Eduardo Paulino dos Santos Jr. at birth, is a designer, musician, filmmaker, and producer who currently lives in Los Angeles.

The Advocate recently spoke with the 35-year-old creator to discuss his latest endeavors, including his unisex fashon designs and the opening of his West Hollywood pop up store. For his WeDu fashion line, Du finds inspiration from the various cultures represented in Angola, an African nation held as a Portuguese colony for nearly 500 years.

Du's collections bear the imprint of Angola's traditional crafts makers and Latin culture; as well as his commitments to gender-inclusive, body-positive, and waste-reducing designs. In 2016, Du produced the documentary Bangologia, about banga (translated as "the essence of style," but specifically referencing African style).

After attending school in the U.S., Du returned to Angola where he thrived, becoming a successful singer (landing on the Billboard Top 20 Latin Songs charts with "Bailando Kizomba"), talent scout, modeling agent (recruiting Angolan top models Maria Borges, Alecia Morais, and Amilna Estevao), and award-winning filmmaker and TV producer. In 2015, Forbes magazine named him one of "The 15 Young African Creatives Rebranding Africa."

"When I moved back to Angola after college, I was reconnecting with my culture, because I'd been out there [in America] since I was 8 years old," he tells The Advocate.

Angola gained its independence in 1975 after nearly 500 years of colonial repression and enslavement, and 15 years of armed rebellion. The new nation almost immediately plunged into a protracted and bloody civil war.

Those dark times colored Du's childhood and can be seen in his fine art collection, "Think, Scream, Repeat," a series of hand-carved wood figurines that Du says are an effort to "reclaim positive childhood memories from a place that was dark and negative."

His carvings evoke Edvard Munch's "The Scream," "Hear No Evil" monkeys, and teddy bear figurines. But Du points to a different inspiration.

The Shameless Collection by Coreon Du, courtesy of the Semba Group

"There's also a symbol in our culture which is from Northern Angola, which is also 'The Thinker' ['O Pensador']," he explains. "But it has a different context, because our Thinker is thinking about the struggles and lamentations of life. It's very much, I would say, a reference of the struggles that we've had during the slavery times. So there is that Thinker, which is an image of an older wise man, who is sort of reflecting about life, and it is a very powerful national symbol."

Despite the obvious violence in the first decades of his nation's independence, Du's impression of that era were of newly empowered idealists, thrust unprepared into harsh political realities of running a nation whose inhabitants didn't get along.

"My grandparents, and parents' generation to some degree, were like a... bunch of hippies trying to make countries work," he reflects. "Because if you look at a lot of, I would say mid-20th century history, a lot of the post-colonial revolts in Africa, after countries gained their independence the big challenge always became: How can we all come together? There was also that challenge of people trying to make countries work. A lot of them were young and idealistic."

Once they got rid of the colonizers, old tribal rivalries threatened to tear many of Africa's new nations apart, even as generations of intermingling meant that the tribes weren't always as distinct as they had once been.

For example, Du says, "One part of my family is from one tribe, the Kikongos, which are in Northern Angola and the Congo. But then, the daughter of the tribal leader, which was my great-grandmother, married a Portuguese white guy and that's how my mom's mom was born."

"Then the other side," he continues, "is the tribe from Luanda, which is a completely different one. Their cultural habits are very different. Their culture is different, their language is different, but we're technically all the same country."

While making the documentary Bangologia, Du traveled across Angola discussing the importance of fashion with tribal leaders.

"I had the honor of meeting the king of the Chokwe people... a nation that [historically] crossed maybe like three, four African countries now," he recalls of the filming. "He was talking about heritage, and sort of how his culture viewed style. And it was very interesting. He talked a lot about how, in his culture, style is ancestral. It's like you wear specific things because your parents, or you wear a specific garment, or a specific piece of jewelry because there's a meaning to your family. A lot of things are passed down every generation."

"When I went to a different tribe, they were like, 'No, things are just for visual pleasure and because they look great.' For example, in the South, where I met a nomadic tribe... along the Okavango.... They have this natural mixture that protects them from the sun. But then, when the temperature lowers, it also keeps up body temperature. They look like they're these people with a beautiful red hue on their skin. And you think it's for vanity reasons, but no, it looks good and it serves a purpose."

Much of Du's work has revolved around discovering and boosting local Angolan creatives, many of whom are queer and/or gender-nonconforming. For a time, his efforts -- both his own creative endeavors and behind the scenes work -- "resonated with the people."

The love for his country and a commitment to those who live there hasn't waned, but Du admits, things have changed.

"Due to security concerns and to an increase of institutionalized homophobia in Angola -- and general intolerance of myself as an out gay man and supporter of visibility and social inclusion of LGBTQ professionals and empowerment of Angolan youth -- as well political intolerance, I have not lived in Angola full-time since late 2014," he explains.

The Shameless Collection by Coreon Du, courtesy of the Semba Group

Although Angola is ahead of the U.S. in adopting a law that prohibits anti-LGBTQ discrimination in employment, the nation's deep Christian roots give it a conservative edge.

There is also "a very big respect for privacy, culturally, it's always been a little bit like 'don't ask, don't tell.' Even for straight people," Du says. Public displays of affection are frowned on, even for those who appear heterosexual. "Private should be private...and because that exists, in a way, we may be not been as oppressive to matters when it comes to the LGBT relationships."

He continues, "If you happen to be in a relationship with somebody of the opposite sex, great. If you happen to be cisgender, great. If you're not, that's your business. That's not my business."

The discussion around same-sex marriage has also been different in Angola, Du says, because, "many of our cultures are polygamic, which means there are people who have multiple spouses. We have that both ways, because although traditionally most cultures [include] one man having multiple wives. But then there are cultures where polygamy is the opposite way [where] there's one female with multiple partners because some of our tribes are matriarchal and not patriarchal."

Du has taken an active role in pushing visibility and acceptance of LGBTQ Angolans in popular culture. For example, with Windeck, the first telenovella that Du produced for Angolan TV in 2012, he says, "since it was about fashion, I was like, 'I think I can get some gay and lesbian characters in there.' Because it's the fashion world, people will be understanding. ...I was actually able to get these very well known straight actors that were sex symbols to play these queer roles, which again is great because in this current situation you do have some allies. And I knew if I had somebody else do it, it would not have been as palatable and not have created a big enough discussion."

"So, I think that part was well received," he says. "But then on the other hand, I did have a lot of conservatives and some religious leaders be like, 'Oh, you're normalizing gay behavior.'"

Things came to a head in 2015, in what Du characterizes as "institutionalized, politically-motivated acts of censorship," particularly of Jikulumessu, an International Emmy-nominated soap opera Du produced that also included positive representations of LGBTQ people. The show was banned from African TV after two of the main male characters shared a kiss. Angolan media outlets accused Du of promoting homosexuality, but public outcry was in his favor, and fans demanded it return in a successful social media campaign.

"I had never been in the closet," Du recalls of that time. "It was a very bothersome ingredient for many people who were in power at the time. There had been other things with gay characters in theater and TV and film but the problem was, for the most part, it was presumed that the people who are behind it were all heterosexuals. So it's a straight person talking about these issues. So it's not a problem. But if it's someone who is queer in any form speaking about these issues, then they thought I was trying to indoctrinate. So that's the thing that was being pretty heavily promoted, that I was trying to...convert straight people."

In Du's written statement, he confirmed, "due to a toxic climate of increasing discrimination and harassment, I made the decision to leave my beloved home country indefinitely at the end of 2017."

Still, he believes, "for the most part people are inherently good, and don't have malice." After creating the "overtly queer" video for his 2012 song, "Set me Free," Du says he "found it very interesting that families, like parents and children, would come and say, 'Oh, we love this video and my kids like the colors and the costumes.' I'm in full-on S&M, tied up and wearing these really outlandish things, and families were like, 'We love the colors and the costumes!'"

These dichotomies in Angolan society allowing for a certain level of homoerotic interactions within the confines of heterosexuality under certain circumstances (particularly in entertainment and performances) are also apparent in the embrace of gender-nonconforming Angolans within the kuduro musical style.

"Looking at kuduro music specifically, it's the only genre of music I know that has never set limitations, that are heteronormative on any of their artists," Du says, "which is why you do have a lot of artists doing very non-heteronormative things on stage. It can be in front of the most conservative audience, and people will think it's OK because within that cultural context, people are free to express themselves. It was the only style of music and art I knew where artists could dress however they want... They could dance very masculine or very feminine regardless of their gender. They could make out with someone of the same gender and not be judged by it."

"I want people to see my art first, my work first before anything else," he says. "So when I had the opportunity, and when I do have the opportunity, I want to make sure that I'm creating a platform for other people to also have that opportunity. So regardless of whether someone is cis, trans, nonbinary, what the color of their skin is, they're welcome as long as they are talented."

In his written statement Monday, Du adds, "Both my artistic and commercial corporate endeavors have always been performed according to the best possible standards and practices, despite being met with constant politically motivated harassment and extreme scrutiny both internationally and inside my country. I have always tried my best to remain gracious and driven to promote positive portrayals of African creativity, despite having had to endure years of ill-willed powerful individuals in my country and beyond attempting to vilify my sexual identity and last name against me. Being independently minded and politically neutral have created numerous hurdles with the powers from back then and to this date; however that has not shaken my commitment to being authentic to what I stand for professionally and ethically."

He concluded, "I will continue to pursue my creative endeavors to the best of my ability and fortunately with continued positive results, in spite of mounting discomfort and pressure of the current socio-political climate in my home country. I continue to have no interest in involving myself with any discussions regarding Angola's politics nor any form of political intrigue involving its institutions or figures. Instead, I will let my body of work of almost two decades speak for itself and portray my values, my commitments, and my professional vision."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.